What did Elon Musk mean when he said he was “dark MAGA?” Exploring this question will certainly take us to a very dark conclusion. Yet, ironically, it is this very conclusion that, once seen in the right light, can liberate us.

This two-part series examines the genuine but misplaced hopes of the millions of US citizens who elected Donald Trump to his second non-consecutive term. Unbeknownst to them, they have voted to live in a Technate administered by what is called “gov-corp.” In so doing, they have taken another step toward a multipolar world order, or “New World Order,” as some have long called it.

Shortly before the November 2024 election, Elon Musk, speaking at a Trump rally in Butler, Pennsylvania, announced, “I’m not just MAGA, I’m dark MAGA.” Only a couple of months earlier Trump had survived an alleged assassination attempt at the same Butler show grounds. Sharing the stage with “bullet-proof” populist hero Trump, an absolute shoe-in for the presidency, Musk seized his moment.

The Make America Great Again (MAGA) acronym is broadly understood. But Musk’s added adjective “dark” is little understood — and implies much more.

Explanations for his “dark MAGA” declaration have ranged from Musk pushing the Dark MAGA meme coin to Musk casting himself as a super-antihero or even an advocate of a violent fascist takeover of the US. None of these claims have addressed his more obvious reference. Musk is one of a cadre of technocrats behind the Trump presidency who promote the ideas encapsulated by the Dark Enlightenment.

Peter Thiel, a co-founder of PayPal along with Musk, is probably the best-known proponent of the Dark Enlightenment while Musk is the best-known proponent of Technocracy. But, as we shall see in this article, these sociopolitical theories have considerable overlap and are mutually reinforcing.

Elon Musk’s Technocratic Heritage

In a 2021 SEC filing, Tesla CEO Elon Musk and Tesla’s then-Chief Financial Officer Zach Kirkhorn officially changed their respective working titles to become the “TechnoKings” of Tesla. This might seem like nothing but irreverent fun—consider that Kirkhorn was also known by the Game of Thrones title of “Master of Coin”—but Musk certainly understands the gravity of Technocracy and the associated term “technocrat.”

Their careful choice of words is an important point emphasized throughout this article. While oligarchs like Musk and Thiel often express ideas in a seemingly flippant manner—or as if the ideas sprang from out of nowhere—these apparent offhand remarks are not meaningless. It is Aesopian language indicative of the core beliefs held by people like Musk, Peter Thiel, Jeff Bezos, and other members of what Council on Foreign Relations think tank member David Rothkopf generously characterizes, in his book on the subject, as the “Superclass“: people who can “influence the lives of millions across borders on a regular basis.”

The “joke” is on us. Or, rather, on those of us who assume it’s all just a joke.

Both Musk and Thiel are members of the “superclass,” though “parasite class” might be a more fitting description for the oligarchy Rothkopf describes. “Insider” Rothkopf’s estimate of around 6,000 individual oligarchs, whose decisions impact the lives of the remaining eight billion of us, seems feasible.

Musk and Thiel are just two among the 6,000 by virtue of being welcomed into the “superclass” by behind-the-scenes oligarchs who do not feature on the published lists of the world’s wealthiest men and women. Musk and Thiel are made men. We are focusing on them because they are prominent accelerationist technocrat supporters of the Trump/Vance administration.

Elon Musk’s maternal grandfather was Joshua N. Haldeman (1902–1974), who hailed from Pequot, Minnesota. In 1906, when Joshua was four, his parents took the family north and settled in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. In 1936, after 34 years of life on the western plains of the US and Canada, Joshua Haldeman moved to Saskatchewan’s provincial capital, Regina, where he established a successful chiropractic business.

Between 1936 and 1941, Haldeman did more than realign spines. He was also the research director and leader of the Regina branch of an up-and-coming entity known as Technocracy Incorporated, shortened to Technocracy Inc. In 1940, while serving in that post, he was arrested by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) for violating Defence of Canada regulations, under which Technocracy Inc. was deemed an “illegal organisation.” As a result, Haldeman was denied entry into the US, where he had intended to deliver a speech promoting Technocracy. He was then fined and given a suspended sentence for heading up the controversial Technocracy Inc.

Following his 1941 conviction, Haldeman joined the Canadian Social Credit Party (Socred), which had been formed in 1932 by evangelist William Aberhart. Socred sought to implement the “social credit” economic theory of British engineer and economist C. H. Douglas. Like Socred, Technocracy was based upon the “industrial efficiency” ideas of engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor (Taylorism). It also dovetailed with the “conspicuous consumption” economic theories of Thorstein Veblen.

C. H. Douglas presented his theory of social credit to tackle what he saw as the inequality of opportunity created by the centralised control and hoarding of resources and wealth. He identified the “macro-economic gap” between retail price inflation and wage growth. He suggested filling that gap by creating the “National Credit Office”—which would be independent of state control—to issue “debt-free” credit to consumers. Part of this National Credit would be used to lower retail prices. The remainder would be distributed to all citizens, irrespective of their personal financial situation, as a way of creating consumer demand for goods. Douglas’ suggestion was an early model of Universal Basic Income (UBI).

Joshua Haldeman’s family of seven, which included a daughter, Maye Haldeman, left Canada in 1950 to set up base in Pretoria, South Africa. As entrepreneurs and adventurers, they travelled extensively. By her own account, Maye Haldeman was close to her parents and adopted their entrepreneurial spirit, sense of adventure and work ethic. Unavoidably, she was also familiar with her parents’ political ideas. Maye recalled that, as a child, she and her siblings would do their “monthly bulletins and photocopy newsletters, and then put the stamps on the envelopes.”

Maye Haldeman married Errol Musk in 1970. Their son, Elon, was born in Pretoria a year later. He was an infant when his grandfather died in a plane crash. Nonetheless, as he was growing up, Elon learned about and became intimately familiar with his grandfather’s political philosophy.

Though Musk was evidently close to his mother, he elected to stay with his father in Pretoria when his parents divorced in 1979. After Elon’s relationship with his father soured, he encouraged his mother to claim her Canadian passport, according to Maye. Her doing so enabled Elon to quickly secure his own Canadian passport, emigrate from South Africa—which he did at age 17—and thereby avoid compulsory military service in that country.

Elon’s ultimate goal was to live and work in the US. But before that, he decided to head from Montreal to Waldeck, Saskatchewan, where, upon returning to his roots, he worked as a farm hand on his second cousin’s farm. There, he awaited his mother Maye’s arrival from Pretoria. She was followed by Elon’s two siblings, Kimbal and Tosca, who also wanted to be closer to the Haldeman side of the family in Canada.

Musk studied at Queen’s College in Kingston, Ontario, for two years before acting upon his aim of settling in America. He transferred to the University of Pennsylvania, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in physics and economics. Subsequently, he interned in Silicon Valley tech companies before abandoning education to pursue his entrepreneurial ambitions.

Fast Forward to Today

In October 2024, a possible spoof account for Amazon billionaire Jeff Bezos posted on Musk’s “X” platform an alluring statement: “The Network State for Mars is being formed before our eyes.” The real Musk enthusiastically replied, “The Mars Technocracy.” To which the Bezos-like account responded, “Count me in.”

As he continues to dream about colonising Mars, Musk has made it abundantly clear which political system he prefers. In 2019, he wrote: “Accelerating Starship development to build the Martian Technocracy.” Note his use of the word “accelerating.” For Musk “accelerating” doesn’t simply mean an increase in velocity.

Musk has long advocated Universal Basic Income. Here’s one instance of his embrace of UBI: At the World Government Summit in 2017, Musk said, “We will have to have some kind of universal basic income.” Another example: In June 2024, speaking with then-Prime Minister Rishi Sunak at the UK-convened first global “AI Safety Summit,” Musk painted a Utopian vision of an artificial intelligence-dominated society and “an age of abundance” before adding, “We won’t have universal basic income, we’ll have universal high income.” In other words, he was suggesting that the masses would have perfect “lives of abundance” enabled by the ultimate AI-controlled distribution of UBI.

Musk desires Technocracy—and a social credit system—just as his grandfather Joshua Haldeman did. This is evident beyond his personal history and his words. Everything Musk does is completely congruent with these dual pursuits. But when we are invited to discuss Technocracy in reference to Mars, we are of course asked to ignore all the evidence that exposes Musk’s and his fellow oligarchs’ attempts to establish a “Technate”—a system of technocratic, totalitarian continental control—here on Earth.

As is the case with many of his oligarch brethren, Musk’s business acumen and his ethics are highly questionable. It appears he has survived and thereafter thrived in business solely because of his network connections, his considerable state backing, and the largess of his investors. As George Carlin wisely observed, “It’s a big club.”

Musk invested more than a quarter-billion dollars to install Trump in the Oval Office. Naturally, he anticipates a return on his investment. In fact, that ROI is a done deal: Musk already makes billions from US taxpayers through a web of government contracts. For tycoons like Musk, money is simply a means to an end: obtaining power. His wealth has positioned him to start seriously implementing his grand vision of Technocracy.

Musk’s dive into Technocracy is underway through the newly established temporary agency in Washington, D.C., he now chairs. Announced last November by Trump, created on his first day in office, and supposedly set to complete its mission by the summer of 2026, the US Department of Government Efficiency, known as DOGE, appears to be a nascent Technocracy.

Venture capitalist Musk and biotech billionaire Vivek Ramaswamy were handpicked to run DOGE with the help of Cantor Fitzgerald CEO Howard Lutnick. Vivik has since departed to run for Governor of Ohio. Lutnick was Trump’s choice to become the US Secretary of Commerce and was recently confirmed. His appointment raises many concerns. Not least of them is his link to Satellogic, a strategic partner of Peter Thiel’s Palantir Technologies. This link reveals Lutnick’s personal investment in the public-private surveillance state that is governed by US and Israeli intelligence agencies.

Yet Lutnick has an even more significant conflict of interest. He is steering Cantor Fitzgerald to back Tether (USDT), a stablecoin that is increasingly purchasing US Treasurys. As we move toward the era of digital currencies, the US government project to save its debt-laden dollar and its fragile economy is closely tied to stablecoins. Thus, as Secretary of Commerce, Lutnick will be in a position to guide the development of markets toward the new US digital economy. We’ll expand on this angle in Part 2.

Perhaps it’s just a coincidence that “the Doge” was the formal title of the chief administrator (magistrate) of the mercantile Venetian Republic. As we shall also discuss in Part 2, there are many reasons to suspect that today’s DOGE acronym is not a mere coincidence.

The departure of Ramaswamy and Lutnick from the DOGE project appears to leave Musk as its sole “CEO.” A corporate monarchy, led by a CEO “king,” (TechnoKing) is in keeping with the theories underpinning the Dark Enlightenment.

The stated purpose of the DOGE is to restructure the federal government to reduce expenditures and maximise efficiency. That goal is in keeping with Taylorism, a foundation of Technocracy.

One of the leading neoreactionaries (we’ll explain this term shortly), Curtis Yarvin, coined the catchy acronym RAGE. It stands for Retire All Government Employees. The parallels between the stated ambitions of the DOGE and the intention of Yarvin’s RAGE are marked.

Apparently, the DOGE will not be an official executive department but will instead operate as a Federal Presidential Advisory Committee, supposedly outside of government. But make no mistake: The DOGE will be inextricably tied to the political process. Its employees will be housed in the former offices of its predecessor, the United States Digital Service. And its helmsman, Musk, will reportedly have a personal office in the West Wing of the White House.

The efficiency ideas of certain nominated experts, starting with Musk, will be given political clout via a new “DOGE” subcommittee of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. This subpanel is chaired by controversial congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA)—often referred to as MTG. On the surface, it may look like an oversight subcommittee with authority over the science, engineering, and technology “experts,” but in practice the “experts” will be effectively controlling the related political policy decisions. This concept of policy designed by technical “experts” is central to Technocracy.

J.P. Morgan Chase Chairman and CEO Jamie Dimon is among those who have welcomed the DOGE plan. Certainly, the proposal to radically reduce or even eradicate US government’s financial regulators appeals to bankers like Dimon. The Trump administration is seeking to seize and centralise control of financial regulators such as the Security and Exchange Commssion (SEC) and the antitrust regulator the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). Consequently, the banks are anticipating a much lighter regulatory touch. Speaking at Davos, J.P. Morgan asset wealth fund manager Mary Erdoes—tipped to succeed Dimon as CEO—said the moves had freed US bankers’ “animal spirits” and set investment banks in “go-mode.”

Given that Elon Musk was neither elected by Americans nor authorized by their representatives in Congress, the DOGE represents a formal shift in political power from the public to the private sector. It is fundamentally a private sector-dominated think tank openly empowered to “restructure federal agencies.” If the DOGE proceeds as suggested, it is clear that, as we pointed out above, elected US representatives—MTG among them—and US senators will not have the upper hand. Indeed, we might question if they are even capable of grasping the ulterior motives of those driving the DOGE concept.

Also, given that Musk and other DOGE supporters—Bezos, for example—have long profited from huge government contracts, and given that the likes of Dimon will doubtlessly be asked to “advise” the DOGE, we see a massive conflict of interest at the heart of the DOGE project. That conflict, like everything else about the DOGE, and its supporters like Bezos, are aligned with Technocracy, for it affords pecking-order privileges to the very technocrats who seek to control a Technate.

An In-Depth Look at Technocracy

To appreciate why people like Musk and Bezos are so enthused by the prospect of Technocracy, we must understand the full extent of Technocracy. We must grasp not just what it is superficially portrayed to be, but also recognize its deep, dark, humanity-mutating, society-altering intentions and aims.

Technocracy does not merely call for technocratic governance—that is, a sociopolitical system where qualified experts, or “technocrats,” rather than politicians, set policy.

Technocratic governance came to the fore during the 2020–2023 pseudopandemic. Medical “experts,” notably Anthony Fauci and other members of the White House Coronavirus Task Force, were put in positions very visible to the public. They were widely seen as leading the policy response—namely, mass “vaccinations,” lockdowns, small business shutdowns, and other imposed-from-on-high mandates designed to enforce and measure worldwide compliance.

But the Technocracy that Musk, Bezos, and other tech “experts” seek to establish implies more than an experiment in the effects of mRNA injections, more than a test of controlling and mesmerizing the masses.

Technocracy is based on the belief that there are technological solutions to all social, economic, and political problems. The Elon Musks and Peter Thiels of the planet and many more of their ilk share this single-minded belief.

For example, when, 20 years ago, Thiel co-founded the impact investment platform called the Founders Fund, its mission statement noted that “technology is the fundamental driver of growth in the industrialized world.” It also declared that the Founders Fund exists to solve “difficult scientific or engineering problems.” If the right technology succeeded, the Founders Fund rationalized it to be the “shortest route to social value.”

Technocracy offers a form of policy response—there is no political “policy” as we understand the term in a Technocracy—as technological solutions to social problems. But this is only a limited aspect of Technocracy. (Keep in mind, faith in technological solutions is not found solely in Technocracy.)

Technocracy is truly unique, unlike any of the sociopolitical, philosophical or economic ideologies familiar to most of us.

In 1937, Technocracy Inc.’s in-house magazine, The Technocrat — Vol. 3 No. 4, described Technocracy as:

The science of social engineering, the scientific operation of the entire social mechanism to produce and distribute goods and services to the entire population.

To give that definition context, we’ll go back two decades to 1911, when American mechanical engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor, arguably the world’s first management consultant, published The Principles of Scientific Management. His book came out at the culmination of the Progressive Era in the United States.

The Progressive Era was a historical period marked by the political activism of the US middle class, who sought to address the underlying social problems—as they saw them—of excessive industrialisation, mass immigration, and political corruption. “Taylorism,” which was fixated on the imminent exhaustion of natural resources and the advocacy of efficient scientific management systems, was part of the spirit of the age.

In The Principles of Scientific Management, Taylor wrote:

In the past[,] the man has been first; in the future[,] the system must be first[.] [. . .] The best management is a true science, resting upon clearly defined laws, rules, and principles, as a foundation[.] [. . .] [T]he fundamental principles of scientific management are applicable to all kinds of human activities, from our simplest individual acts to the work of our great corporations.

Taylor’s ideas jibed with the theories of economist and sociologist Thorstein Veblen. Veblen proposed that economic activity isn’t just a function of supply and demand, utility and value, but that it evolves with society and is thus shaped also by psychological, sociological and anthropological influences.

Veblen is perhaps best known for his theory of “conspicuous consumption.” He observed that the wealthy signalled their social status through ostentatious display of their purchasing power: expensive properties, cars, jewels, etc. Within the hierarchical class structure, aspiring classes tried to emulate the conspicuous consumption of the class above them. Veblen contended that the cascade effect of this social climbing created demand for superfluous goods and services and that the net economic impact was therefore hopeless inefficiency and wasted resources.

In The Engineers and the Price System, Veblen suggested that technocratic engineers should undertake a thorough analysis of the institutions that maintained social stability. Once the institutions were understood, those with technological expertise should reform them, improve efficiency, and thereby engineer society to be less wasteful. Shortly, we’ll discuss how this idea was later adapted by the accelerationist neoreactionaries.

Both Taylor and Veblen were focused upon maximising the efficiency of industrial and manufacturing processes. That said, they both recognised that their theories could be extended to a wider social context. It was the more expansive application of their proposals that beguiled the oligarchs of the day.

In 1919, Veblen was one of the founding members of a John D. Rockefeller-funded, New York City-based private research university in New York called The New School for Social Research (later renamed The New School). This progressive educational model soon led to the creation of the Technical Alliance, a small team of scientists and engineers notably including not only Veblen but also Howard Scott, who would come to lead the group.

The Technical Alliance was reformulated in 1933 after an enforced hiatus was prompted by Scott’s exposure as a fraudster. He had falsified some of his credentials—as, apparently, had C. H. Douglas. Post-hiatus, Scott was joined by M. King Hubbert—who would later become globally renowned for his vague and generally inaccurate “peak oil” theory—and others. The members of the Technical Alliance renamed themselves Technocracy Inc.

Technocracy was thoroughly outlined in Technocracy Inc.’s 1933 publication of its Technocracy Study Course. According to the study course’s technical specifications, society should be separated into what the advocates of Technocracy (from now on referred to as “technocrats”) call a “sequence of functions.” In this sequence, society as we know it is removed. Instead, centralised control of all human interactions and behaviour is proposed as part of the “social mechanism.”

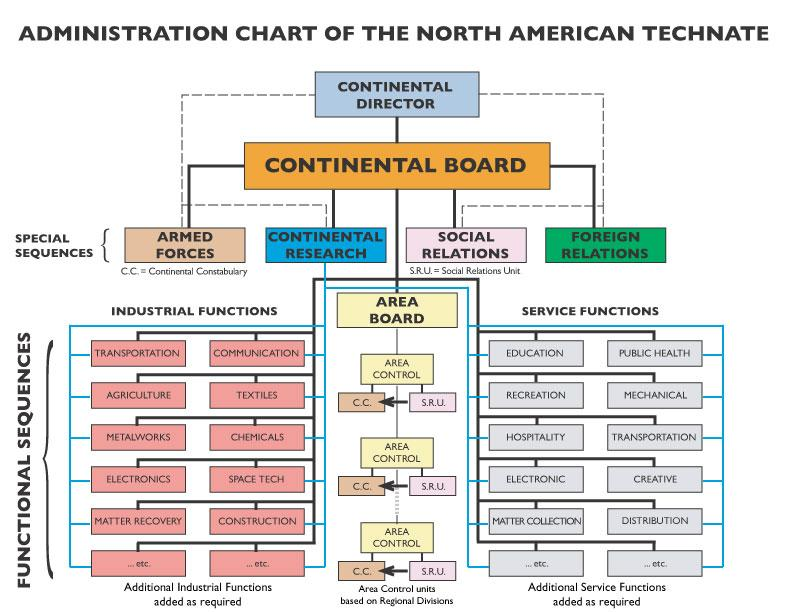

An entire “social mechanism” subjected to technocrats is called a Technate. A Technate is designed to work “on a Continental scale”—that is, on each continent, or Technate, whose boundaries are drawn on a map. The Technate of North America map includes Greenland, Canada, the United States, Mexico, parts of Central America, northern South America, Caribbean islands, and the eastern Pacific Ocean.

There are no national governments in Technocracy. Nation-states are abolished in each continental Technate.

Driven by the assumed precepts of efficiency, technocrats deem the centralised control of all resources essential:

Technocracy finds that the production and distribution of an abundance of physical wealth on a Continental scale for the use of all Continental citizens can only be accomplished by a Continental technological control, a governance of function, a Technate.

Each function, or “Functional Sequence,” is categorised as either an industrial sequence, a service sequence, or a special sequence. For example, the “Transportation Functional Sequence” and the “Space Tech Functional Sequence” are both industrial sequences. The “Public Health” and “Education” functional sequences are among the service sequences. The “Special Sequences” are those related to security and defence (Armed Services), scientific and technological development (Continental Research), governance of the population (Social Relations), and the Technate’s relationship with other Technates or nation-states (Foreign Relations).

Administration of an entire Technate—each continent—is further subdivided by “Regional Divisions,” each defined according to their longitude and latitude boundary markers and designated by a corresponding grid-reference number. “Area Control” is an administrative rather than a functional sequence. The Technocracy Study Course specifies what that means:

[An Area Control] is the coordinating body for the various Functional Sequences and social units operating in any one geographical area of one or more Regional Divisions. It operates directly under the Continental Control.

The whole system is overseen by “Continental Control” (shown as the Continental Board above) and ultimately by the “Continental Director”:

The Continental Director, as the name implies, is the chief executive [CEO] of the entire social mechanism. On his immediate staff are the Directors of the Armed Forces, the Foreign Relations, the Continental Research, and the Social Relations and Area Control. [. . .] The Continental Director is chosen from among the members of the Continental Control by the Continental Control. Due to the fact that this Control is composed of only some 100 or so members, all of whom know each other well, there is no one better fitted to make this choice than they.

To be clear: each entire continent—a Technate—is controlled by a self-appointed body which selects its great leader—the Continental Director—from within its own ranks. This self-appointed body controls everything in the Technate.

These early technocrats were supposedly trying to devise a classless system that would provide “lives of abundance” for all. Musk’s words often echo the specific meanings defined by Technocracy Inc. When, for instance, Musk spoke of “an age of abundance,” he was referring to Technocracy. Unfortunately, the original technocrats purported aspirations for a classless society appear to have been inspired either by unimaginable evil or hapless naïveté. Take your pick!

For example, 1930s technocrats viewed all crime simply as a product of the inequality inherent in the capitalist Price System; we’ll cover the “Price System” in a moment. Because technocrats looked upon the “human animal” as little more than a behavioural automaton, they either chose to ignore or didn’t even recognise—let alone account for—other possible motivations for crime besides economic inequality, such as megalomania. Consequently, power-hungry people like the Rockefellers, who recognised that there are other incentives for human behaviour besides practical necessity, viewed Technocracy in terms the technocrats could either barely comprehend or decided to ignore.

The technocrats’ seemingly woeful grasp of the human sciences led them to imagine a Technate that would enable some kind of spontaneous order to emerge—”spontaneous natural priority,” they called it. They rejected the principle that “all men are created equal”—largely, it seems, because they didn’t understand it. In their minds, it had “no basis in biologic fact.”

Upon analysing the behaviour of cow herds and chicken flocks, the technocrats identified a pecking order—from which they derived so-called “peck-rights”—as an explanation to justify the totalitarian, hierarchical social mechanism they were advocating for humans:

Certain individuals dominate, and the others take orders. These dominant ones need not be, and frequently are not, large in stature [referring to cattle and domestic fowl], but they dominate just as effectively as if they were. [. . .] The greatest stability in a social organization would be obtained where the individuals were placed as nearly as possible with respect to other individuals in accordance with ‘peck-rights,’ or priority relationship which they would assume naturally. [. . .] There must be as far as possible no inversion of the natural ‘peck-rights’ among the men.

Regardless of the intentions of technocrats who first designed Technocracy, the appeal of this system for oligarchs is obvious. Technocracy constructs a “social mechanism,” controlled by those who claim “peck-rights,” specifically engineered to facilitate the ultimate form of totalitarianism.

As mentioned above, citizens of the Technate are described as “human animals” and are viewed as programmable machines. The scientific operation of the social mechanism—Technocracy—enables the “service” (labour) of the “human animal” to act as the “human engine” for the efficient operation of the various Functional Sequences.

The technocrats flatly rejected concepts such as the human “mind” and “conscience” and “will.” These constructs, they said, belonged to humanity’s “ignorant, barbarian past.” To them, a human being was nothing more than an “organic machine” that makes a certain variety of “motions and noises,” similar, according to the technocrats, to a dog or a vehicle.

As explained in the Technocracy Study Course, the Technate would maximise the “efficiency” of the Technate by socially engineering—behaviourally controlling—the “human animal”:

Practically all social control is effected through the mechanism of the conditioned reflex. The driver of an automobile, for instance, sees a red light ahead and immediately throws in the clutch and the brake, and stops. [. . .] If they are taken young enough, human beings can be conditioned not to do almost anything under the sun. They can be conditioned not to use certain language, not to eat certain foods on certain days, not to work on certain days, not to mate in the absence of certain ceremonial words spoken over them, not to break into a grocery store for food even though they may not have eaten for days.

Tying this terrifying oppression together was a new monetary system designed to tackle the problems the technocrats saw with the capitalist “Price System.” Much like the proponents of Socred, the technocrats viewed the inequality of wealth and resource distribution as a major problem.

The capitalist “Price System” was thought “wasteful” and therefore unacceptably “inefficient,” largely because the “money” used to measure prices was generated by bank lending (debt). The technocrats referred to fiat currency as a “generalized debt certificate.”

The technocrats therefore determined that the capitalist “Price System” inevitably led to both class inequality and conspicuous consumption as the holders of the debt accrued more wealth than anyone else. Conspicuous consumption, in turn, led to the inefficient allocation of resources into pointless production, expenditure, and vanity projects. So, they proposed a new monetary system based upon the energy cost of production.

Corresponding “Energy Certificates” would better reflect productive work done, as opposed to wasteful credit (debt) consumed, because “energy is measurable in units of work—ergs, joules, or foot-pounds.” Thus, Energy Certificates could be equitably distributed—by the Distribution Sequence—across the Technate, based on the energy required to perform the function.

The technocrats recognised that some functions require more energy than others. The Transportation Sequence construction of a new railroad would require more energy than a single “human animal” working on constructing that railroad. The Distribution Sequence would manage the resultant “fair” allocation of Energy Certificates:

[E]nergy can be allocated according to the uses to which it is to be put. The amount required for new plant, including roads, houses, hospitals, schools, etc., and for local transportation and communication will be deducted from the total as a sort of overhead, and not chargeable to individuals. After all of these deductions are made, [. . .] the remainder will be devoted to the production of goods and services to be consumed by the adult public-at-large. [. . .] Thus, if there be available the means of producing goods and services [. . .] each person would be granted an income[.]

Put another way (with quote marks around Technocracy’s words): “If” there are remaining means, after those with sufficient “peck-rights” have taken the resources they need for their function—”a sort of overhead”—the “remainder” would be allocated “fairly” to the “human animals” and considered sufficient for them to perform their function.

Each issued Energy Certificate would be non-tradable and could be used only for the purchase of resources, goods, and services provided by Continental Control within the Technate.

The Distribution Sequence would record the details of every group or individual to whom the Energy Certificates were allocated and would then monitor how that Energy Certificate was used.

The degree of centralised control inherent in Technocracy is almost beyond imagination:

[O]ne single organization is manning and operating the whole social mechanism. This same organization not only produces but distributes all goods and services. Hence a uniform system of record-keeping exists for the entire social operation, and all records of production and distribution clear to one central headquarters. Tabulation of the information [contained on the Energy Certificates] provides a complete record of distribution, or of the public rate of consumption by commodity, by sex, by regional division, by occupation, and by age group.

With Energy Certificates allocated to the individual and recording all their personal details, the surveillance state is complete. Continental Control will have oversight over every citizen and will be able to monitor and control whatever they buy and wherever they go. In other words, in a Technocracy, all human behaviour is watched and rationed.

Despite their expressed aversion to the capitalist Price System, the technocrats were not antagonistic to the accumulation of wealth. They simply redefined wealth in their own technocratic terms.

In 1933, the authors of the Technocracy Study Course also published their Introduction to Technocracy, in which they wrote:

Technology has introduced a new methodology in the creation of physical wealth. [. . .] Physical income within a continental area under technological control would be the net available energy in ergs, converted into use-forms and services over and above the operation and maintenance of the physical equipment and structures of the area. [. . .] This method of producing physical wealth and measuring its operation precludes the possibility of creating any kind of debt.

Usury—that is, the issuance of nearly all fiat currency as debt repayable with interest—is undoubtedly a key instrument with which today’s oligarchs amass wealth, which they then convert into sociopolitical power. It is useful to note that the word “wealth” means “prosperity in abundance of possessions or riches.” “Riches” implies “an abundance of means.” The etymology of the word “means” defines it as “resources at one’s disposal for accomplishing some object.”

Technocracy places all resources under the command and control of a select few, who are then free to accomplish whatever objective they desire—across an entire continent—by rationing all resources to whomever they choose, whenever they wish, as they see fit. In a Technocracy, the “select few” who have “peck-rights” over and above everyone else do not need monetary wealth. Technocracy promises to deliver the zenith of Aristotelian oligarchy.

To say Technocracy is radical would be a massive understatement. We think in terms of political “isms,” but words like “communism,” “fascism “or “feudalism” don’t come close to describing the extent of the radical tyranny intrinsic to Technocracy.

In 1965, Technocracy Inc. published a written exchange between its founder, Howard Scott, and assistant professor of economics J. Kaye Faulkner. The conversation was later re-released under the title The History and Purpose of Technocracy.

Scott wrote to Faulkner:

Technocracy has always contended that Marxian political philosophy and Marxian economics were never sufficiently radical or revolutionary to handle the problems brought on by the impact of technology in a large size national society of today. [. ..] We have always contended that Marxian communism, so far as this Continent is concerned, is so far to the right that it is bourgeois. It is well here to bear in mind; the technological progression of the next 30 minutes invalidates all the social wisdom of previous history. [. . .] Technology has no ancestors in the social history of man. It creates its own.

As Scott’s words indicate, the technocrats foresaw that the rapid advance in technology would inevitably present both immense opportunities and risks. In an effort to mitigate the risks, the technocrats’ proposed solution was to embrace technology and purpose it to the service of more “efficient” government—i.e., a Technate.

This notion of a technological “singularity” threatening to surpass humanity’s ability to adapt would later inspire the perhaps even more radical political philosophy of the accelerationist neoreactionaries. There are many commonalities between the two sociopolitical theories.

Technocracy, both then and now, is literally inhuman. It elevates technological development above morality. As Taylor made clear, “the system must be first.”

People like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos want to install a Technocracy and live in it—or at least make us live in it. Why? Do they hope we will all live “lives of abundance” under Technocracy? Or do they envisage themselves as elitist members of Continental Control, with a free hand to socially engineer the rest of us, whom they view as a herd of “human animals”?

What do you think?

The Accelerationist Neoreactionaries

Just as Technocracy is based upon the analysis of the “social mechanism” and the subsequent “efficient management” of “Functional Sequences,” so the Dark Enlightenment—also known as the neoreactionary movement (NRx)—is based upon the deconstruction and redistribution of power held by the real ruling entity. The neoreactionaries called this entity “the Cathedral.”

Once the “administrative, legislative, judicial, media, and academic privileges” of “the Cathedral” are properly understood and quantified, they can be “converted into fungible shares” to be owned and traded by “sovereign corporations”—sovcorps—that will form a “patchwork” of “neostates”—neocameralist-states, to be exact—as a result of “neocameralism.”

Thus, the state can be separated from the “ruling entity”—the Cathedral—and can be run more efficiently as a corporate structure called “gov-corp.” This structure is very similar to the efficient management of the “Functional Sequences” forming the “social mechanism” suggested by Technocracy.

Admittedly, there is quite a lot to unpack here.

Building on the work of Karl Marx, in 1942 the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter theorised that capitalist economies constantly evolve due to the cyclical disruption caused by innovations that destroy old markets and create new ones. He popularised the term “creative destruction” to describe this theoretical economic growth process, which, he said, was fundamental to capitalism. Schumpeter emphasised that emergent technology had the potential to disrupt, overturn, and renew the associated socioeconomic and sociopolitical power enjoyed by capitalist monopolies. Therefore, creative destruction also implied a realignment of the social and political order.

During the mid-1990s, a diverse group of iconoclast scholars working out of the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit (CCRU) of Warwick University in the UK and led by the philosophers and cultural theorists Sadie Plant, Mark Fisher, and Nick Land, combined their thoughts about Schumpeter’s creative destruction with their exploration of “deterritorialization.” A product of the critical theory of the Frankfurt School, “deterritorialization” suggested that any sociopolitical “territory”—whatever it may encompass—would ultimately be altered, mutated or destroyed, only to reemerge as something else following the process of “reterritorialization.”

Considering deterritorialization an inevitability and viewing capitalist “creative destruction” as an essential sociopolitical and economic evolution, the CCRU cyberpunks (led by Fisher and Land) noted that the rapid improvements in modern computation—quantum computing, for example—enabled successive forward technological leaps at ever-shorter intervals.

A technological singularity—or simply the singularity—in which technological growth becomes self-perpetuating, was seen as unavoidable. The technological feedback loop meant deterritorialization would be automatic. It would accelerate sharply and outstrip humanity’s ability to intervene or adapt to it, according to the CCRU.

Therefore, the task before society is to either adapt or die. Adapting means that creative destruction of capitalism must be embraced and intensified—not just because it is a socioeconomic phenomenon but because it is a desirable “schema” to implement. The creative destruction of social, economic and political systems is a proposed survival strategy that itself needs to accelerate to keep pace with the inevitable deterritorialization as we speed towards the singularity—or some other apocalypse.

In his 1967 novel Lord of Light, American science fiction writer Roger Zelazny depicted revolutionaries who wanted to rapidly transform their society by enabling greater public access to technology. Zelazny called his fictional revolutionaries “accelerationists.” The term was subsequently popularised by professor of critical theory Benjamin Noys. Note: This was prior to Nick Land labelling his interpretation of Schumpeter’s creative destruction “accelerationism.”

In 2016, Land explained:

Deterritorialization is the only thing accelerationism has ever really talked about. [. . .] In this germinal accelerationist matrix, there is no distinction to be made between the destruction of capitalism and its intensification. The auto-destruction of capitalism is what capitalism is. “Creative destruction” is the whole of it [. . .]. Capital revolutionizes itself more thoroughly than any extrinsic ‘revolution’ possibly could.

Leading CCRU figures Nick Land and Mark Fisher in the UK and, notably, Curtis Yarvin in the US were part of the growing neoreactionary movement (NRx). Neoreactionaries fall on both the left and the right of the traditional political divide, but all neoreactionaries are accelerationists.

The associated term “accelerator” has certainly caught on. In 2011, researchers from the UK business and innovation “charity” Nesta published a discussion paper in which they noted the rapid rise of “accelerator” programmes, starting in the US and subsequently spreading to Europe and beyond:

The number of accelerator programmes has grown rapidly in the US over the past few years and there are signs that more recently, the trend is being replicated in Europe. From one accelerator programme, Y Combinator in 2005, there are now dozens in the US that are funding hundreds of startups per year. There have already been a number of high-profile startup successes from accelerator programmes.

Now 20 years old, Y Combinator (YC) applied the accelerationist approach to venture capitalism. Notable successful start-up ventures followed. Stripe, Coinbase, and Dropbox were among YC’s winners. In 2011, Peter Thiel protégé Sam Altman (who, alongside Thiel, Musk and others, co-founded OpenAI) joined YC and in 2014 became its president.

Besides the US government, the UK government and EU members states have fully embraced accelerationism. The UK government, for example, runs numerous accelerators.

Accelerationism has been conspicuously used to develop defence and surveillance technology. Consider the D3 accelerator which is reportedly “entirely focused on military-related startups.” Initially focusing in Ukraine, the “Dare to Defend Democracy” (D3) accelerator is a public-private partnership that adopts the accelerationist approach to startups focusing exclusively on AI enabled intelligence, cybersecurity, and military technology.

The D3 accelerator’s leading investors include former Google CEO Eric Schmidt. Together with Peter Thiel, Elon Musk, and other investors in AI solutions, they have combined to use the Ukrainian battlefield as a test bed. In addition, Thiel’s Palantir and Musk’s Starlink experimentation collaborated with the Pentagon to develop Project Maven. The project deploys AI to rapidly analyse vast amounts of data to generate automated targetting. Accelerationism’s influence on public-private AI start-ups in the defence sectors on both sides of the Atlantic is already significant. We’ll explore this further in Part 2.

But, for all its winners, the accelerationist approach also creates many losers we never hear about.

[A]ccelerators typically provide services through a highly selective, cohort-based programme of limited duration (usually 3–12 months). Services often include assistance in developing the business plan, investor pitch deck, prototypes, and initial market testing. [Accelerators] base their business model on equity from the startups. This means that they are more growth driven, typically aiming to produce companies that will scale rapidly or fail fast, thus minimising wasted resources.

This selective, high-impact, creative destruction-based model of venture capitalism covers its potential losses by seizing equity from the start. The start-ups that don’t make it are left with nothing. Their investors seek to recoup what they can.

The Cathedral

Writing under the pen name Mencius Moldbug between 2007 and 2014, Curtis Yarvin published a series of essays in which he laid out his various “UNQUALIFIED RESERVATIONS” (a title that runs across the bottom of each essay).

In 2014, Yarvin took a break from writing as Moldbug to focus on his business interests, with Thiel’s assistance. In 2013 he received start-up funding from Thiel for his company Tlön and its Urbit platform, a decentralised peer-to-peer (P2P) network technology company. (Note: Yarvin shifted his focus back to writing in May 2020, issuing an announcement that he was partway through his book, Gray Mirror Of The Nihilist Prince.)

Yarvin (as Moldbug) identified what he called “the Cathedral” as the primary target for creative destruction. Fellow neoreactionary Michael Anissimov described the Cathedral as “the self-organizing consensus of Progressives and Progressive ideology represented by the universities, the media, and the civil service. [. . .] The Cathedral has no central administrator, but represents a consensus acting as a coherent group that condemns other ideologies as evil.” In other words, the Cathedral is not a formal structure of the state but rather the dominant progressive ideology of those exercising a controlling influence over the state.

In essence, the neoreactionaries view “the Cathedral” as the governance effect of the belief system maintained by the Establishment—the ruling class. Yarvin observed that the Cathedral prevails as an informal “institution rather than a person.” Thus, he argued, traditional approaches to political reform were useless. The real ruling entity, he reasoned, existed more as a shared ideology and as a resultant set of agreed-upon objectives held by a dominant class than as an identifiable political structure:

[T]he power structures that bind the Cathedral to the rest of the Apparat [bureaucracy] are not formal. They are mere social networks. [. . .] [T]here is nothing you can do about this structure. You can’t prevent people from emailing each other.

The NRx claims that the Cathedral champions modern, left-leaning progressivism. The fact that there is very little evidence of any Establishment commitment to egalitarian social reform is just one of many glaring errors and woeful assumptions littered throughout neoreactionary political philosophy and accelerationism more broadly. We’ll cover the most egregious errors and assumptions shortly.

While progressive mores are frequently touted by members of the Establishment, this is evidently a perception management tactic and part of social engineering. The Establishment likes to be seen as progressive and certainly prefers that we adopt progressive values, but there is no evidence that the Establishment conducts itself in keeping with progressive ideology. Nonetheless, there is truth to Curtis Yarvin’s observation that the Cathedral, expressed in neoreactionary terms, “does not wish to relinquish power.”

The NRx uses the word “democracy” when referring to “representative democracy.” Yet “democracy” and “representative democracy” are two separate, distinct, and almost diametrically opposed political systems. Representative democracy is based on every sovereign individual devolving all of their decision-making “authority” to a select few elected politicians, whereas “democracy” sees every sovereign human being retaining and exercising their own sovereign authority through the rule of law.

This confusion of definitions is a common NRx error. So common, in fact, one has to wonder if it is simply an “error” or a deliberate obfuscation. Whatever the case, the NRx is right to highlight the near-religious zealotry with which said Cathedral extols so-called “democracy.” By declaring representative democracy righteous, the NRx contends that the Cathedral establishes what is effectively a moral dictatorship.

Yarvin wrote:

The real problem is that, as a political form, democracy is more or less a synonym for theocracy. (Or, in this case, atheocracy.) Under the theory of popular sovereignty, those who control public opinion control the government.

As “democracy” hinders the necessary creative destruction and is propelling humanity like lemmings towards the cliff-edge of the singularity, axiomatically democracy must be destroyed and a better form of government—a kind of corporate monarchy—installed, per Yarvin:

The only way to escape the domination of canting, moralizing apparatchiks [the Cathedral and its acolytes] is to abandon the principle of vox populi, vox dei, and return to a system in which government is immune to the mental fluctuations of the masses.

Cameralism can be described as the science of public administration. It perceives the state as a business that runs a country. Cameralism unfolded in Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries, as large, centralised states emerged. The systematic gathering and analysis of statistical data became increasingly important for state administrators and planners.

Cameralism breaks the function of the state into three parts: (1) public finance (cameral), (2) the administration of order, and (3) oeconomie. The latter determines the relationship between state and society. It is social engineering using economics and other tools. Cameralism, in all its functions, serves the efficiency of the state.

The neocameralism of the NRx applies cameralism to the Cathedral. The envisaged post-neocameral state, in which the government is “immune to the mental fluctuations of the masses,” can best be realised, or so say the neoreactionaries, by converting the state into a corporate structure.

Yarvin explained it this way:

Let’s start with my ideal world — the world of thousands, preferably even tens of thousands, of neocameralist city-states and ministates, or neostates. The organizations which own and operate these neostates are for-profit sovereign corporations, or sovcorps.

The Dark Enlightenment

French philosopher Gilles Deleuze (1925–1995) and French psychoanalyst and political activist Félix Guattari (1930–1992), who wrote a number of works together, argued that while capitalism set free the acquisition and distribution of resources, its architects were highly territorial, tending toward monopoly, which ultimately resulted in capitalism bringing “all its vast powers of repression to bear.” Therefore, they argued, “deterritorialization” was essential. As capitalism was inherently self-destructive, the task, they said, was to “accelerate the process.”

Echoing the “conspicuous consumption” theories of Veblen, French philosopher and sociologist Jean-François Lyotard posited that consumerist workers in modern capitalist societies did not want emancipation. Their materialistic desires meant they enjoyed “swallowing the shit of capital,” Lyotard wrote.

Building on these theories and pushing the concepts presented by Mencius Moldbug (Yarvin) to the maximum, former CCRU leader Nick Land published “The Dark Enlightenment“ in 2012. If Technocracy is inhuman, Dark Enlightenment borders on psychopathic.

Land contended that the postmodern tenets of liberal democracy—by which he meant liberal “representative democracy”—created an inescapable sociopolitical “vector” that would inevitably lead to a “new dark age” as “Malthusian limits” would unavoidably “brutally re-impose themselves.” Only an accelerationist neoreaction could avert the inevitable totalitarian catastrophe.

Land continued:

For the hardcore neoreactionaries, democracy is not merely doomed, it is doom itself. Fleeing its approaches is an ultimate imperative. The subterranean current that propels such anti-politics is recognizably Hobbesian, a coherent dark enlightenment, devoid from its beginning of any Rousseauistic enthusiasm for popular expression.

By agreeing to Rousseau’s “social contract” myth, propagated by the Cathedral, everyone condemned themselves to “democratic politics,” Land argued. The result of “democratization” is a capitalist “sovereign power” that runs the state to everyone’s detriment and to seemingly inescapable corruption:

[T]he dynamics of democratization [are] fundamentally degenerative: systematically consolidating and exacerbating private vices, resentments, and deficiencies until they reach the level of collective criminality and comprehensive social corruption. The democratic politician and the electorate are bound together by a circuit of reciprocal incitement, in which each side drives the other to ever more shameless extremities of hooting, prancing cannibalism, until the only alternative to shouting is being eaten.

Land highlighted the accelerationist view that the Cathedral assumes a postmodern “central dogma” and, as a result, maintains a misplaced “absolute moral confidence.” Unquestioningly accepted by the brainwashed public, the “secularised neo-puritanism of the Cathedral” deifies the “evangelical state.” Consequently, all opposition to it is deemed heresy. Land argued that nothing could be more intolerant of dissenting views or less inclusive.

The problem with the Cathedral, Land declared, was that while technology was capable of “accelerating development,” the “rent-seeking special interests”—the ruling class—who maintained the Cathedral swallowed all the benefits. There were no political solutions to this capitalist conundrum because their neo-puritan faith in so-called liberal democracy rendered populations incapable even of understanding, let alone tackling, the overwhelming power of the Cathedral. Land considers this a societal mental disorder that Yarvin called “demosclerosis”—an intransigent, self-destructive faith in the Cathedral.

The Cathedral had integral morbidity, and post-WWII globalization had spread the sickness. To maintain demosclerosis, the Cathedral’s only solution was to consume ever more to retain the neo-puritanical beliefs of the faithful. Land called this condition “modernity 1.0.” It necessitated the constant expansion into new markets, to the point where Land predicted that the “Eurocentric” model would be abandoned. Anglo-American power would thus be diffused as the Cathedral sought to roll out “modernity 2.0.”

Writing in 2012, Land said:

Modernity 2.0. Global modernization is re-invigorated from a new ethno-geographical core [the East], liberated from the degenerate structures of its Eurocentric predecessor, but no doubt confronting long range trends of an equally mortuary character. This is by far the most encouraging and plausible scenario (from a pro-modernist perspective), and if China remains even approximately on its current track it will be assuredly realized.

The Dark Enlightenment suggests that modernity 2.0 merely postpones the inevitable failure to adapt to the singularity. A true “Western Renaissance” could only be realised with the demise of the extant global Cathedral. Therefore, every crisis should be accelerated and exacerbated in an attempt to break the Cathedral’s hold:

To be reborn it is first necessary to die, so the harder the ‘hard reboot’ the better. Comprehensive crisis and disintegration offers the best odds. [. . .] Because competition is good, a pinch of Western Renaissance would spice things up, even if — as is overwhelmingly probable — Modernity 2.0 is the world’s principal highway to the future. That depends upon the West stopping and reversing pretty much everything it has been doing for over a century, excepting only scientific, technological, and business innovation. [Emphasis added.]

Observe that, from the neoreactionary perspective, “scientific, technological, and business innovation” are the only valuable Cathedral attributes. As neoreactionaries incorrectly think sovereignty implies nothing more than the power to exert authority over another and as the Cathedral possesses the ultimate alleged “sovereignty,” neocameralism can be used to audit Cathedral sovereignty and thereby run the state more effectively.

While the word “sovereignty” certainly implies “superiority,” the libertarian concept of self-ownership, or individual sovereignty, is more than just ignored by the accelerationist NRx. It is wholeheartedly rejected. The proponents of the Dark Enlightenment describe themselves as libertarians, but are using that term in a bizarre sense.

Land at least acknowledged the existence of a ruling class, but the Dark Enlightenment is based on the misconception that oligarchs simply pay for political favours. Once the oligarchs’ path to monetary bribery is removed, they can safely be ignored:

[T]he ruling class must be plausibly identified. [. . .] It is [only] necessary to ask [. . .] who do capitalists pay for political favors, how much these favors are potentially worth, and how the authority to grant them is distributed. This requires, with a minimum of moral irritation, that the entire social landscape of political bribery (‘lobbying’) is exactly mapped, and the administrative, legislative, judicial, media, and academic privileges accessed by such bribes are converted into fungible shares.

Thus, the useful “functions”—or “chambers,” in neocameralist terms—of the Cathedral can be “mapped” and converted into freely transferable shareholdings.

Yarvin suggested breaking nations into neostates run by the shareholders of sovereign corporations—sovcorps. Land, perhaps adopting a more traditional cameralist position, envisaged converting the entire nation into a business enterprise run by gov-corp:

The formalization of political powers [. . .] allows for the possibility of effective government. Once the universe of democratic corruption is converted into a (freely transferable) shareholding in gov-corp, the owners of the state can initiate rational corporate governance, beginning with the appointment of a CEO. As with any business, the interests of the state are now precisely formalized as the maximization of long-term shareholder value.

In a practically identical fashion to Technocracy, the Dark Enlightenment proposes dictatorship. Instead of a Continental Director of Continental Control, it advocates for a CEO of gov-corp. It is still a select few who rule with absolute authority and impunity.

Obviously, there is no democratic accountability of any kind—not even representative democratic accountability—under the totalitarian rule of gov-corp. Indeed, politicians and politics would become obsolete. Nevertheless, like the technocrats, the accelerationist neoreactionaries were, in their own seemingly naïve way, trying to address government corruption and its impacts.

In the Dark Enlightenment, gov-corp would act as a service provider of effective government. Citizens would become its “customers.” They could therefore expect value for their money, and they could make a complaint if they were dissatisfied:

If gov-corp doesn’t deliver acceptable value for its taxes (sovereign rent), they can notify its customer service function, and[,] if necessary[,] take their custom elsewhere. Gov-corp would concentrate upon running an efficient, attractive, vital, clean, and secure country, of a kind that is able to draw customers.

It is difficult to know where to start criticising this absurd idea. Whether they are called “sovereign rents” or “taxes,” no one chooses to pay them. The notion that a customer “buys” a service implies that they are equally free to choose not to buy it. Yet the only choice offered by the NRx’s gov-corp is to either pay up or get out. As Land puts it, absent politics of any kind, “no voice, free exit.” For billions of people this is not remotely possible.

The neoreactionaries’ appreciation of oligarchy is monumentally facile. Land openly acknowledges that the proposed “owners of the state” are those who would have sufficient means to “buy out” the Cathedral’s existing “stakeholders”—that is, its “owners.” So, who does he imagine will run gov-corp but the oligarchs who already “own” the state? Gov-corp does not challenge the “ruling class.” Instead, it hands total control of society and state over to the “ruling class” on a gold platter.

Citizens can already make a complaint to government through a variety of mechanisms, including lobbying, petitions, protest, and other forms of activism. Elections make no difference precisely because government is always corrupted by oligarchs who, while they sometimes squabble, essentially agree on the direction they want humanity to head. To be honest, the other existing routes of complaint don’t really work either, for more or less the same reason.

The Dark Enlightenment solution to this accurately identified problem is to “formalise” every avenue of dissent and sell it off to oligarchs, who are trusted by the neoreactionaries to operate a fair and just “customer service function.” This is not a plausible solution of any kind from humanity’s perspective.

There is every reason to suspect that this so-called solution is an attempt to mollify fools and convince them to buy into the Dark Enlightenment. Frankly, humanity is despised by the neoreactionaries, who wish to see it entirely dispossessed.

The Cathedral would hold nearly all “sovereignty,” but the share of “sovereignty” held by regular humans would be negligible. Rather than address this logical conclusion, however, the Dark Enlightenment treats human beings as practically irrelevant. As Land sees it:

Insofar as voters are worth bribing, there is no need to entirely exclude them from this calculation, although their portion of sovereignty will be estimated with appropriate derision.

Land’s eugenical tendency is obvious when he claims that “people are, on average, not very bright.” Since, in Land’s eyes, the citizenry is worth so little and their share of sovereignty is practically nil, it is best to treat them as the largely clueless customers of gov-corp. In light of looming singularity, the question, according to Land, is how to maximise the useful function of these customers in order extract the appropriate “sovereign rent” from them.

His suggestion is that we should all become “technoplastic beings.” This will make us “susceptible to precise, scientifically informed transformations.”

Land writes:

‘Humanity’ becomes intelligible as it is subsumed into the technosphere, where information processing of the genome — for instance — brings reading and editing into perfect coincidence. To describe this circuit, as it consumes the human species, is to define our bionic horizon: the threshold of conclusive nature-culture fusion at which a population becomes indistinguishable from its technology.

Essentially then, in accordance with the Dark Enlightenment, the accelerationist solution to humanity’s ills is to end humanity.

Once we are “technoplastic beings”—transhuman cyborgs—in a world where “biology and medicine co-evolve,” we will cross the “bionic horizon,” as Land calls it. At that point, we can finally kill God and abandon the “essence of man as a created being.” We will be free to sacrifice our humanity and embark upon our “new evolutionary phase.”

As valued customers who are rendered intelligible only by melding with technology, we can all prostrate ourselves and our children before the sovereignty of gov-corp. Under the watchful eye of our illustrious CEO, we can be programmed as required. The result? Finally, at long last, we will have an effective government. After all, “the system must be first.”

The Accelerationist Left

In 2008, two Canadian left-leaning neoreactionaries, Alex Williams and Nick Srnicek, published the #ACCELERATE MANIFESTO for an Accelerationist Politics. In this treatise, the pair were responding to Mark Fisher’s thoughts on “capitalist realism.” (The following year, Fisher turned those thoughts into a book called Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative.) Fisher had observed that, after the Soviet Union collapsed, no viable political-economic alternative to capitalism had been offered. Probably quoting Slavoj Žižek, Fisher had written, “[I]t is easier to imagine an end to the world than an end to capitalism.”

Fisher argued that the left had failed to challenge neoliberalism, which he described as a separate but reinforcing component of modern capitalism. Considering the inequities wrought by neoliberalism, Fisher urged the left to embrace an accelerationist approach to capitalism. He identified neoliberalism, rather than progressivism, as the founding faith binding what Land and Yarvin called “the Cathedral.”

Like his counterparts on the right, Fisher contended that technological growth was unstoppable. He argued that the traditional left’s attempt to recreate a socialist society without accounting for the homogenising effect of modern technology was an act of futility. If the hope was to make meaningful use of progressive political theory, the left needed to embrace capitalist realism and deploy accelerationism to creatively destroy and “deterritorialize” neoliberalism to ensure a progressive, post-capitalist reterritorialization.

In their #ACCELERATE MANIFESTO, Williams and Srnicek accepted capitalist realism and said:

In this project, the material platform of neoliberalism does not need to be destroyed. It needs to be repurposed towards common ends. The existing infrastructure is not a capitalist stage to be smashed, but a springboard to launch towards post-capitalism.

Applying neocameralism to neoliberalism, they added:

[T]he left must take advantage of every technological and scientific advance made possible by capitalist society. We declare that quantification is not an evil to be eliminated, but a tool to be used in the most effective manner possible. Economic modelling is — simply put — a necessity for making intelligible a complex world. [. . .] The tools to be found in social network analysis, agent-based modelling, big data analytics, and non-equilibrium economic models, are necessary cognitive mediators for understanding complex systems like the modern economy. The accelerationist left must become literate in these technical fields.

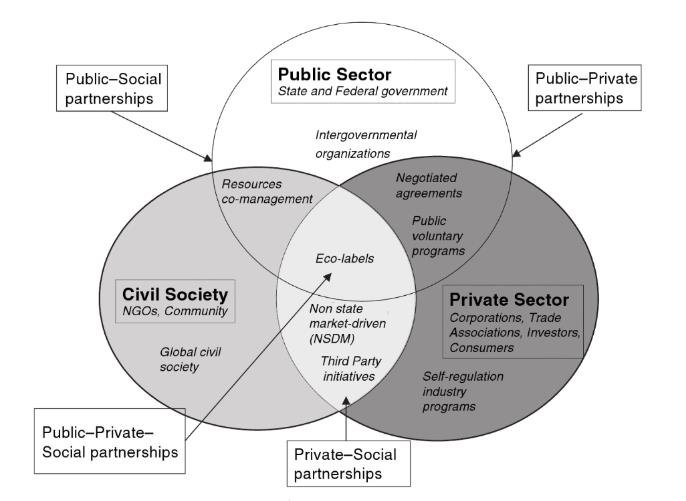

As accelerationist leftists who are pursuing a progressive future, the co-authors advocate a “sociotechnical hegemony” to ensure that “production, finance, logistics, and consumption” are “reformatted towards post-capitalist ends.” They promote public-private partnership—stakeholder capitalism. And they believe that “governments, institutions, think tanks, unions, or individual benefactors” should work together to create “an ecology of organisations, a pluralism of forces.”

This “ecology” of public and private institutions could, Williams and Srnicek envisioned, create “a new ideology, economic and social models, and a vision of the good” and design new “institutions and material paths to inculcate, embody and spread them.” Working together, this partnership of stakeholders would construct “a positive feedback loop of infrastructural, ideological, social and economic transformation, generating a new complex hegemony, a new post-capitalist technosocial platform.”

It is somewhat humorous that, despite all their talk of a “sociotechnical hegemony,” the accelerationist left has been divided from the neoreactionary right by the same old disagreements—not to mention some degree of animosity. Harshly critical of Land in particular, Williams and Srnicek described Land’s inhuman model of accelerationism as “a simple brain-dead onrush,” whereas their own model promises a more human-centred “navigational” accelerationism.

Any human being who would like to see future generations of humanity thrive would be hard-pressed to choose either the #ACCELERATE MANIFESTO or the Dark Enlightenment. Both are deeply rooted in transhumanism. Instead of being programmed to be good customers of gov-corp, we’d be programmed to be outstanding progressives under sociotechnical hegemony. Of the latter, Williams and Srnicek write:

Any transformation of society must involve economic and social experimentation[,] [. . .] fusing advanced cybernetic technologies [. . .] with sophisticated economic modelling [. . .] and a democratic platform instantiated in the technological infrastructure itself, [. . .] employing cybernetics and linear programming in an attempt to overcome the new problems. [. . .] The left must develop sociotechnical hegemony: both in the sphere of ideas, and in the sphere of material platforms. Platforms are the infrastructure of global society. They establish the basic parameters of what is possible, both behaviourally and ideologically.

In truth, accelerationist neoreaction, on both the left and the right, outlines nothing other than a future technological and sociopolitical dystopia. There is absolutely no reason to imagine that hegemony of any kind is capable of delivering anything but tyranny. Like the technocrats, the accelerationist neoreactionaries seem equally unable to grasp that there will always be megalomaniac oligarchs set on “accomplishing some object,” no matter how deranged their objective may be.

Disillusionment with representative democracy is no reason to hand over totalitarian sociopolitical control systems to oligarchs. Accelerating towards hegemony is not a solution. Unless you are an oligarch, it is a stupid and suicidal proposition.

Neither Technocracy, accelerationism nor the Dark Enlightenment exist within our familiar political paradigms. They are so far outside the Overton window that we can’t even discuss them without either being embroiled in pointless and redundant debates about whether they are communist or fascist or being subjected to eye-rolling scorn.

To be frank, it makes little difference what we hoi polloi believe. The oligarchs who are conversant with these political philosophies are evidently trying to bring them to fruition in our lifetime. We ignore the consequent cultural revolutions and social engineering projects at our peril. Make no mistake: They are already underway.

Consider Land’s darkly enlightened determination that we must reject “any Rousseauistic enthusiasm for popular expression”—the common perception of the “social contract.” We are now seeing his objective transition into [public] policy.

President Trump has come to power backed by technocrats like Elon Musk and neoreactionaries like Peter Thiel. One of Trump’s first acts as president was to announce a $500 billion public-private infrastructure investment project called “Stargate.” The aim is to construct the data centre and power generation capacity needed for the development and rollout of artificial intelligence (AI) systems.

The Stargate public-private consortium brings the US government into a partnership with OpenAI, Oracle, and Softbank. Thiel’s protégé, Sam Altman, is the CEO of OpenAI. Speaking shortly after Trump’s announcement, Altman made a statement thick with Aesopian language. He told reporters:

I think technology does a great deal to lift the world to more abundance and to better prosperity. [. . .] I still expect that there will be some change required to the social contract. [. . .] [T]he whole structure of society itself will be up for some degree of debate and reconfiguration.

Darkly Enlightened Christianity

Irrespective of the various religious rites practiced by different Christian denominations or of the sectarian divisions to which they give rise, the unifying values of all genuine Christians—love, compassion, humility, integrity, and justice—are easy to appreciate and respect.

But right-leaning members of the neoreactionary movement, including Yarvin and Land, take exception to what they consider a progressive translation of those Christian values. Consequently, self-proclaimed Christian neoreactionaries have adopted a warped reinterpretation of the traditional Christian values most of us recognise.

“Universalism” is a Christian theology that preaches the doctrine of universal reconciliation with God. Christian Universalism maintains that anyone—Christian or not, saint or sinner—can find salvation through Jesus Christ. Universalism often holds that there is no permanent damnation to Hell because “the Lord will not cast off forever.”

The theology of Universalism is aligned with Mainline Protestantism, which emphasises social justice and personal salvation and offers more liberal and progressive interpretations of scripture. Yarvin attacks Christian Universalism as an extreme form of Calvinism, which, he says, dictates that “all dogs go to Heaven and there is no Hell.” His objection is to the inference that “everyone is part of the elect.”

The belief that we are all equally deserving of grace is contrary to the dogma of the neoreactionary right. Remember, the NRx proclaims that humanity’s “portion of sovereignty” is worthy only of “derision.”

Consequently, the NRx neologise “Universalism” to mean the synthesis between “the mainline Protestant and secular Nationalist movements.” Yarvin argues that US secular nationalism has become “internationalism”—globalism—and that “nationalism” has consequently become “an inappropriate term.”

The neoreactionaries reference an article published in Time magazine in 1942, titled “Religion: American Malvern” as alleged proof that progressive liberal theology has mutated and merged with progressive, political globalism. This is considered to be to the detriment of both Christian beliefs and nationalism. Though the article links the political corruption of the church in the US with globalists like John Foster Dulles, it does not demonstrate that Christian theology and progressive political ideology are intertwined.

Nonetheless, as the Cathedral is defined as the supposed dominant progressive ideology of the ruling class, Yarvin concludes that political progressivism is a “sect of Christianity”—and not a sect he embraces.

Frankly, this appears to be little more than linguistic trickery. Other than the fact that reform is common to both political progressivism and theological liberalism, the neoreactionaries’ suggested marriage of the two seems tenuous. It is almost impossible to follow Yarvin’s and Land’s reasoning, to the point where many have questioned if there is any.

Yarvin insists that modern Christianity itself has become a core component of the “nontheistic sect” of NRx-defined Universalism—the neo-puritanical faith in the Cathedral. Consequently, according to the NRx, the neoreactionaries who oppose Universalism are viewed as literal heretics by the neo-puritan acolytes of the Cathedral—that is, everyone who is not a neoreactionary.

Yarvin rejects this notion and sees those who embrace liberal theology—progressivism—as the true heretics. It is the NRx, he posits, that seeks to restore the true Christian faith:

If a Christian who believes his or her faith is justified by universal reason is a Universalist, a Christian who believes his or her faith is justified by divine revelation—in other words, a “Christian” as the word is commonly used today—might be called a Revelationist.

For NRx Christians like Peter Thiel, imposing gov-corp and removing the stultifying influence of the progressive Universalism is the Christian thing to do. In their view, the true revelation is that “real” Christians reject liberal theology and hold to a more literal reading of scripture. Combined with his sociopolitical philosophy, this theology has evidently led Thiel, and presumably others who share his faith, to adopt supposed Christian values most of us would struggle to recognise as Christian.

Today, the TechnoKings—such as Y Combinator CEO Garry Tan—and many of the leading lights in the Mainstream Alternative Media (MAM)—are more openly discussing and promoting their Christian faith. Take Russell Brand, for example. Brand’s proselytising is popular on the Thiel-backed Rumble video-sharing platform, where many MAM heavyweights have prospered.

As noted by the UK’s Christian Today, Hulk Hogan, Shia LaBeouf, Rob Schneider, Kat Von D, Candace Owens, and Ayaan Hirsi Ali are also among the many celebrities and “talking heads” to have very conspicuously converted to Christianity (mainly Catholicism) in recent months. Before we assume this indicates a resurgence in Christian values, perhaps we should first look at what those values might be.

It is tempting to see the fashion for openly advocating your Christianity as a marketing strategy, particularly in the US. The “Bible Belt” represents a sizeable demographic and usually a Republican heartland. But there is more to it.

Peter Thiel has been something of a faith leader among the TechnoKing class and has long been open about his own allegedly Christian beliefs. Thiel is also an enthusiast and former student of the philosophy of René Girard (1923–2015). His personal Christian values are evidently heavily influenced by his sociopolitical and philosophical beliefs. They diverge considerably from the Christian values we have discussed to this point.

Girard argued that people’s desire to imitate others—mimesis—led them to covet objects and services, ascribing them corresponding and often irrational value. His mimetic theory is largely consistent with Veblen’s conspicuous consumption.