MAHA’s “Handpicked” Biosecurity Veteran

As the Trump administration has spent its first few months in The White House constructing the physical and digital infrastructure required for a pre-crime, technocratic police state, little attention has been paid to the ways in which the institutions ostensibly dedicated to “public health” are helping build out this digital control grid. As Unlimited Hangout has been reporting for many years now, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, a prominent subgroup of the surveillance state has emerged at the intersection of Big Tech, Big Pharma and the military industrial complex — one that is laying the groundwork to implement the final frontier of mass surveillance: the bio-surveillance apparatus.

During his first term, Trump implemented the notorious Operation Warp Speed, the Pentagon-ran COVID-19 response plan which issued emergency deregulatory measures and massive funding for the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines. Now, his second administration has successfully managed to become associated with COVID-era dissidence. This was primarily accomplished through Trump successfully securing the endorsements of figures who were skeptical of the official line on COVID-19, most prominently comedian and podcaster Joe Rogan and longtime environmental litigator and founder of Children’s Health Defense, Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

Since taking office, however, the second Trump administration has consistently contradicted this unofficial commitment to the spirit of COVID-era dissent and public health institutional overhaul. Just last week, the President touted Operation Warp Speed as one of the “most incredible things ever done in this country.” The week before, he announced an initiative to enable the vast sharing of individuals’ health data across a myriad of “health systems and apps,” in partnership with Pentagon-contracting Big Tech companies. More quietly, however, Trump nominated a seasoned official of the biosecurity apparatus named Susan Monarez to be the Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Monarez, whose background is perfectly in line with this technocratic approach to healthcare that the administration has embarked on, was “handpicked” by Kennedy after the previous nominee, Dave Weldon, withdrew his nomination in March. Monarez had been acting director of the CDC for several months and was confirmed at the end of July with little fanfare.

Susan Monarez is a biosecurity veteran who has a long history embedded in what could be described as a gray zone of public governance — one where national security merges with healthcare. These connections and her life’s work suggest that Monarez is a useful tool, knowingly or not, of the biosecurity/surveillance apparatus, a group which has helped expand the sprawling American mass surveillance system under the auspices of wellness, mental health and innovation.

While a lack of a detailed digital footprint makes this exact history difficult to track down precisely, it is likely that her entry into the world of militarized science began at Stanford University when she was carrying out her work as a postdoctoral researcher. The Chair of her department notably boasted deep ties to some of the leading figures in the genetic science boom of the latter half of the 20th century — figures whose research was entangled with the eugenics movement of that era and the increasing securitization of science that occurred in the midst of the Cold War.

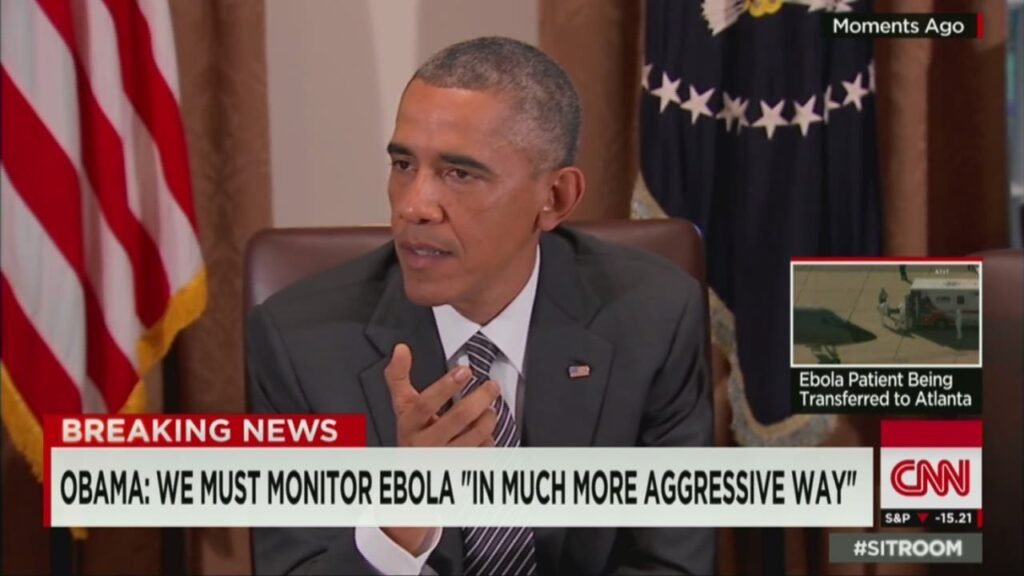

From Stanford, Monarez was catapulted into prestigious positions within DHS, HHS, as well as the White House itself. Notably, the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa emerged during Monarez’s tenure in the Executive Branch, and she played an important role in the government response. That outbreak may have marked one of the first times that the US commissioned the pre-crime, mass surveillance company Palantir with conducting biosurveillance during a public health epidemic. It most certainly established a significant step towards the total transformation of the US public health system into a militarized extension of the surveillance state.

Monarez’s time working in agencies such as the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) and the Homeland Security Advanced Research Projects Agency (HSARPA) made Monarez a perfect candidate for the position she maintained until she was most recently nominated to be the director of the CDC: the Deputy Director of the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H). From its conception, the HHS-housed ARPA-H was meant to serve as a “health” version of the Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA).

Monarez’s appointment to the CDC, however, indicates further melding of America’s public health institutions with the national security state. While it has been more or less given that most heads of public health agencies in recent years must be supportive of technocratic biotechnology measures, Monarez has presided over significant initiatives and programs that have deepened the militarization of healthcare. She has also been appointed to be the Director of the CDC within the context of the ever-increasing integration of the pre-crime company Palantir, which privatized much of the George Bush-era Total Information Awareness mass surveillance project –– including its “Bio-surveillance” component — into government.

Furthermore, her time as the Deputy Director of ARPA-H may foreshadow the kind of initiatives she will head at the CDC; namely, the blatant digitization of health and acceleration of invasive biotechnology aimed at fracturing the complexity of human biology into observable, consumable and exploitable data points.

As this article will make clear, Monarez’s tenure in government is likely a direct product of the decades-long militarization of academia. Her stints at BARDA, the National Security Council, HSARPA, DHS and most recently ARPA-H are illustrative of the broader technocratic, surveillance-obsessed transformation of public health that has accelerated since the COVID-19 pandemic. That trend appears poised to persist under the second administration of Donald Trump.

To get a closer look at how Monarez may have entered this world, it is worth first investigating the connections that the Chair of her department at Stanford, Mark M. Davis,1 has to some of the industries and ideologues that, over time, have merged to form the biosurveillance state: eugenicists and the oligarchic technocrats who dominate Big Tech. Davis’s connections capture the biosecurity-focused academic environment where the future CDC director began her professional career as well as the spooky world of military-linked science she subsequently entered.

Stanford University — Where Academia and Defense Meet

Nearly five decades before Monarez attended Stanford’s biology and immunology program, the US military establishment was in a frenzy with its officials trying to figure out how they should respond to the Soviet Union’s successful launch of its small satellite named Sputnik into outer space.

Despite its beach-ball size, Sputnik injected paranoia into the United States, for as Yasha Levine details in his book Surveillance Valley, “[Sputnik] was thrust into orbit by hitching a ride atop the world’s first intercontinental ballistic missile. This was both a demonstration and a threat. If the Soviet Union could put a satellite into space, it could also deliver a nuclear warhead to just about any spot in the United States.”

The American response to this “threat” launched the Space Race, and along with it the creation of the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA, which later became DARPA) — the agency that pioneered the now prominent military technological development method of funding universities, private research facilities and defense contractors to develop tech for the U.S. Armed Forces. Stanford — Monarez’s alma mater — was among the most prominent universities that was tapped by ARPA to increase the surveillance power and military might of the US empire, tying at least some of the university’s most consequential research to the interests of the national security state. This relationship has persisted into the present day.

Mark M. Davis — the Chair of Monarez’s department during her time at Stanford, and thus the person that likely hired Monarez’s other professors — is a figure whose connections demonstrate the sprawling dark side of big-moneyed militarized science succinctly, and whose background may provide insight into how Monarez landed herself in the underbelly of the US public health system.

Mark M. Davis and Leroy Hood

Mark M. Davis’ parents divorced when he was quite young. His mother was an architect, but fluctuated between being a stay-at-home mom and working. His father was in the Navy during WWII, and went on to become an executive at the Pentagon-contracting International Business Machines Corporation (IBM) for decades after his service.

During his teen years, Davis was a slightly above average student at a below average high school. He coasted his way through this chapter of his life by relying on his natural wits and expansive literary knowledge, often as a means of avoidingthe studious rigor that would shape his later academic career.

It was in high school, however, that his mom gifted him a copy of The Double Helix by legendary geneticist James D. Watson. The autobiographical account of Watson’s discovery of the structure of DNA left a notable impression on a young Davis, though he may have not realized it at the time. Davis later went on to study DNA in 1973 during his time pursuing his bachelor’s degree at John Hopkins University. There, he joined the lab of Michael Beer. Beer was a pioneer of sorts in this terrain as at the time he was attempting to sequence DNA—a mission that had yet to be accomplished.

Indeed, it appears that it was the untreated nature of this subject that allured Davis into the field, for as he put it: “[Beer] made me realize, as he explained…that this was really a central issue that hadn’t all been sorted out by [James D.] Watson and [Francis H.C.] Crick — which would have [hypothetically] made it history and therefore not my concern. But [in actuality,] there really was a lot there that was unknown and could have a lot of significance.”

This eventually led Davis to the lab of Leroy Hood at Caltech. While Beer was a figure at the forefront of DNA research, Hood revolutionized the field in momentous ways that are still felt today. Most notably, he was responsible for the creation of the automated DNA sequencer, which “showed that sequencing data could be collected directly to a computer …[and] developed programs to automatically interpret the data to produce an actual sequence.” In the years leading up to Hood’s automated DNA sequencer, Davis co-authored multiple studies with Hood — including one with The Double Helix author James D. Watson.

This computerized, technological invention of Hood’s made the once tenuous and laborious process of sequencing DNA a more feasible endeavor — which ultimately made it possible to launch The Human Genome Project (HGP), the NIH-funded effort that sought to map the entire human genome.

The Human Genome Project nearly achieved this goal, mapping 92% of the human genome, and went on to heavily influence and expand the field of biotechnology and predictive medicine — a fitting contribution, given Hood’s Caltech lab was the first one to “combine biology and engineering, using biological knowledge to determine which technologies should be developed in order to solve specific biological problems.” In fact, a protein sequencer Hood had developed earlier in his career led to the founding of a company called Applied Molecular Genetics and the creation of its blockbuster drug erythropoietin, which just so happened to be “the first biotech product to reach $1 billion in sales.”

These achievements, correctly or not, are looked back on with reverence and awe by mainstream accounts — but viewing this era of science through rose-tinted glasses disables any onlooker from seeing the darker ideology that quietly rose with, and arguably propelled upward, the study of genetics and biotechnology that was growing at this time.

The initial call for The Human Genome Project was first published in 1986, the same year that Hood’s automated DNA sequencer was invented, by a German-born geneticist named Walter Bodmer. A major contributor to the study of population genetics, Bodmer was elected as a Fellow of the Eugenics Society, rebranded later as the Galton Institute and even more recently rebranded as the Adelphi Genetics Forum as of 1961 (p. 971). The organization was founded with the aim of promoting the study and research of eugenics — a racist pseudo-science based in the study of how to best arrange human reproduction to increase the rate of «desirable» traits within a population. That same year, Bodmer conducted his postdoctoral research in the lab of Joshua Lederberg at Stanford University (p. 3). Lederberg, who inspired biodefense pioneer Robert Kadlec, was also the former president of Rockefeller University and served as a key consultant to the Pentagon on issues of biological weapons, among other things.

Bodmer’s connections to the field of eugenics and national security notably do not exist within a vacuum. As The Human Genome Project and Hood’s and Davis’s later associations exemplify, the meeting of eugenics and genetic science is actually indicative of a symbiotic relationship between the two fields that has persisted into the present day. As Eugenics Society member David Galton noted in his book, Eugenics: The Future of Human Life in the 21st Century, that The Human Genome Project, among other technologies, enabled advancements such as the ability of parents to artificially select which genes their child receives in order to create “designer babies,” and notes that The Human Genome Project, among other advancements, have “enormously expanded the scope of eugenics.”2

Indeed, it was James D. Watson — a racist eugenicist and the author of The Double Helix book that had inspired Mark M. Davis years before — that the NIH chose to head The Human Genome Project in 1990. Watson, who holds beliefs such as the idea that Black people have genetically inferior intelligence than other races, first encountered Leroy Hood at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in 1967, which Watson went on to head for sixteen years. During his time at Cold Spring Harbor, Watson met with Eugenics Society member Bodmer (p. 986), and even co-authored a research paper with Mark M. Davis and Leroy Hood.

Watson’s leadership at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory was quite suitable for a eugenicist such as himself. Nearly sixty years before his time there, the eugenicist Charles Davenport became its director and set up the Eugenics Record Office (ERO). As James Corbett notes in his book Reportage, Davenport envisioned the ERO as a place to store “a comprehensive registry documenting the ‘pedigree’ of every American…”3

According to Davenport himself, the Office retrieved this data through “our numerous charity organizations, our 42 institutions for the feebleminded, our 115 schools and homes for the deaf and blind, our 350 hospitals for the insane, our 1,200 refuge homes, our 1,300 prisons, our 1,500 hospitals, and our 2,500 almshouses. Our great insurance companies and our college gymnasiums have tens of thousands of records of the characters of human bloodlines…”4 While Davenport’s idea had a particularly racist tinge to it, his objective of scouring institutions for health data and uniting them into a single location to be observed under the scrutiny of elite bureaucrats never died — indeed it prevails today in the halls of ARPA-H, and was worked on by Susan Monarez herself.

That, however, will be discussed later in this investigation. In the meantime, let us return to Watson, whose government work extended beyond the National Institutes for Health — specifically involving the Pentagon and biological weapons. President John F. Kennedy, who was a prominent advocate of technological military modernization through his support of DARPA, had Watson serve on his chemical and biological warfare advisory panel from 1961 to 1964.

According to the Harvard Crimson, Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist Seymour Hersh said that Watson “admitted in an open letter to him that he had spent a great deal of time on the panel searching for a ‘satisfactory incapacitating agent.’” Watson’s time aiding the Pentagon in its biological weapons research during the Cold War highlights another element of the revolution taking place at the time within genetic science; the field’s mutually beneficial relationship with the national security state.

As one former high-level Pentagon official told Hersh in his 1968 Chemical and Biological Warfare book, «There’s a revolution in biological sciences, just as there was in the physical sciences in the 1920’s. It [genetics] is analogous to quantum theory. A huge area of science is in ferment — and it may have military implications and advantages for us.«5

Further demonstrative of these converging interests was Hood’s next step after Caltech, when he made a big move to the University of Washington Medical School to found the first cross-disciplinary biology department, the Department of Molecular Biotechnology — a move that was financed to the tune of $12 million by none other than Bill Gates, notably a longtime Pentagon contractor. Gates funded the project because he and Hood shared “a grand vision;” namely, using computer technology to read and manipulate all of the “vast genetic encyclopedia…cover to cover, three billion nucleotides long: The Human Genome Project” (emphasis added).

Gates’ funding is particularly worth nothing because he also has connections to the eugenics movement, though they may not be as outwardly obvious as Watson and Eugenics Society member Bodmer. The Gates Foundation has a history of investing in projects such as global “family planning” initiatives focused on delivering low- and middle-income countries birth control, at times in conjunction with the Rockefeller Foundation. Eerily, before World War II, the Rockefellers were some of the most prominent funders of eugenics research, even funding departments that (albeit after the known time period of Rockefeller-funding) employed figures like Ernst Rüdin in the 1920s,6 who went on to become a key architect of Nazi Germany’s eugenics program and who worked on the Third Reich’s sterilization policy. The flow of Rockefeller money into eugenics research was not contained within Germany, however — along with other robber barons, John D. Rockefeller funded Davenport’s Eugenics Research Office at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York.

James Corbett, who has researched the history of eugenics extensively, told mehow in the aftermath of WWII, the field of eugenics became associated with the Nazis, and “thus had to go underground.» This was “an explicit and conscious decision,” Corbett told me, citing the General Secretary of the British Eugenics Society’s memorandum in 1968. The memorandum suggested that in an effort to deal with the diminishing success of the Society’s recruiting campaign since 1946, it “should pursue eugenics by less obvious means, that is by a policy of crypto-eugenics”7 to, as Corbett put it, “carry on the dream of eugenics under another name.”

An excerpt from a book written by Julian Huxley of the Eugenics Society immediately after the war appears to corroborate Corbett’s claim that eugenicists in this period indeed recognized the political impossibility of their agenda, and the need to revitalize it in some way. The book was written representing the newly created United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), which the Rockefellers have been affiliated with since its creation. In the book, Huxley laments “even though it is quite true that any radical eugenic policy will be for many years politically and psychologically impossible, it will be important for UNESCO to see that the eugenic problem is examined with the greatest care, and that the public mind is informed of the issues at stake so that much that now is unthinkable may at least become thinkable.”8

Since that 1968 memorandum, Corbett speculates, eugenics policies were “rebranded” and “sold as a way to help save poor countries and peoples from the scourge of overpopulation.” Given this context, despite whether Gates considers himself a eugenicist or is even aware of these connections himself, some of his “health”-focused endeavors –– such as an implantable birth control device that could “be turned on and off with a remote control,” his idea to ration healthcare based on an individual’s perceived value to society, or his effort to promote long-acting reversible contraceptives in Africa with a company whose initial mission was “improving the biological stock of the human race” –– exist within a darker context than their seemingly benign, technocratic motivations.

Yet, Hood’s time at the University of Washington would not be the last time his professional work received massive funding from Gates. He would later go on to found the Institute for Systems Biology (ISB), a spin-off of the work he was doing in his lab at the University of Washington. Like his time at UW, ISB focused on Hood’s shared interest with Gates; bioinformatics, or the “use of information technology to store and analyze genetic information.” Gates has funded ISB to the tune of millions of dollars over the years (see here and here).

And to wrap up this bundle of eugenics- and national security-linked science connecting all the way to Monarez’s time at Stanford, in 2015, Mark M. Davis — Monarez’s Department Chair during her postdoctoral years — was selected to head a new center at Stanford to “accelerate efforts in vaccine development” called the Stanford Human Systems Immunology Center. The way in which this center came to fruition? A $50 million grant from the Gates Foundation. Stanford Report announced that it would “draw upon a repertoire of technologies, many of which have been pioneered at Stanford, to provide a detailed profile of the human immune response” (emphasis added).

Davis, as Monarez’s Department Chair, likely played an important role in cultivating the staff at Stanford’s biology and immunology postdoctoral research program. These professors who Monarez likely encountered or took classes with include figures such as David Relman, a longtime government operator who has sat on the National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity and who issued a questionable report on Havana Syndrome, and Garry Nolan, a Pentagon contractor and CIA ufologist who has his own strange connections to Havana Syndrome.

These figures demonstrate that the academic environment which preceded her government tenure was rife with links to the shadowy side of academia. Whether or not someone at Stanford helped bring Monarez into the biosecurity apparatus is unclear — yet it was only a few months after her graduation that she began her stint at HHS’ Biomedical Advanced Research Projects Agency (BARDA), a newly established government department that emerged in the wake of the Anthrax attacks, and from the minds of biosecurity-obsessed Cold Warriors.

Stockpiling In the Public Sector

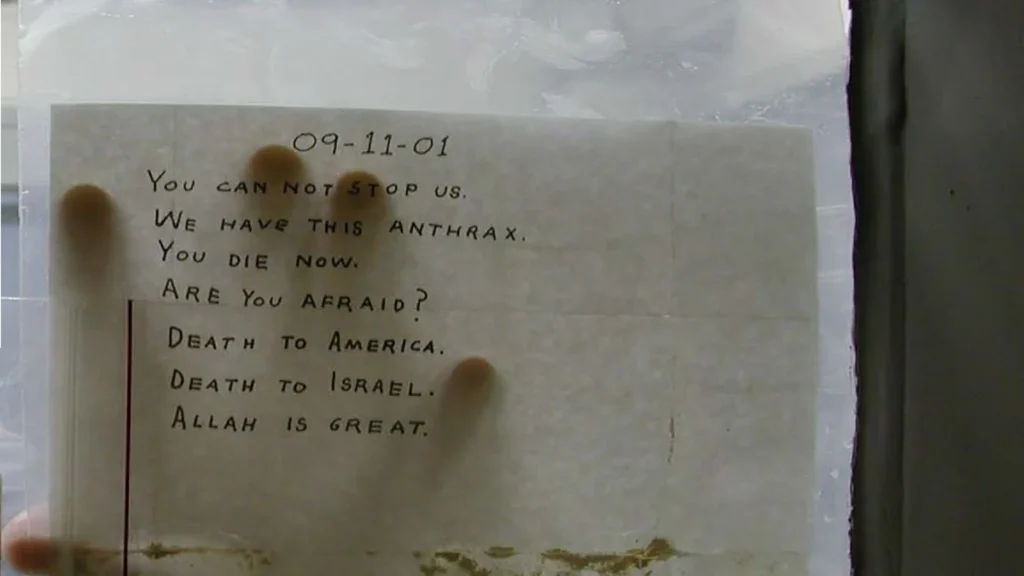

BARDA was created in the backdrop of a post-Amerithrax United States. The false flag that associated Iraq with Al Qaeda without evidence injected panic into the American psyche, and it was in this period of trepidation that the HHS head Tommy Thompson began warning of a flu pandemic and vaccine shortages, calling for the funding of an American “stockpile of emergency vaccines for smallpox and anthrax.” Over the next few years, this stockpile funding was achieved, primarily through the Project Bioshield Act of 2004, and eventually managed by BARDA. The history of the stockpile’s and BARDA’s inception, however, ties its origins deeply to the world of national security and the paranoia surrounding the War on Terror.

The stockpile was the result of a years-long effort that had been cooked up by bioweapons-focused and Big Pharma-connected Cold Warriors — namely the Air Force doctor and intelligence officer Robert Kadlec, along with some of his mentors like William Patrick III. Kadlec had been advocating for this stockpile as far back as 1995,9 notably in between the trips he’d taken to Iraq along with Patrick in search of the Iraqi government’s weaponized anthrax program. Though the pair never found any evidence of such a program, throughout the 90s Kadlec was drafting hypothetical scenarios at the National War College of potential ways in which American adversaries could use bioweapons to wage war against the US,10 and Patrick was participating in private meetings with Clinton on biological weapons. In these meetings, Patrick described their use as inevitable and emphasized that a terrorist could make even the most dangerous pathogens in their “garage.”

With the prospect of terrorist-waged biowarfare marinating in Clinton’s mind, in this period the Arkansas-native President claimed that Saddam Hussein was “developing nuclear, chemical and biological weapons and the missiles to deliver them,” despite a lack of any intelligence to prove so. Clinton’s fear eventually materialized into legislation when he requested an emergency budget supplement request in 1998. In it was “$51 million for pharmaceutical and vaccine stockpiling activities at CDC.” It soon passed, and the Strategic Pharmaceutical Stockpile (SPS) was born.

A few years later, the fear that the prospect of bioterror instilled in Clinton spread like a virus to the entire American population in the wake of an actual “bioterror” attack; Amerithtrax. While 9/11 showed that an anomaly like a plane-hijacking could destroy critical infrastructure of the normally protected United States, the anthrax attacks made Americans perceive terrorism as a new element of daily life, something that could be covertly unleashed through an item as innocuous as a letter, and wreak havoc and death through invisible spores and contamination.

Sometime before the anthrax attacks in the wake of 9/11, Kadlec became the special advisor on biological warfare to George W. Bush’s Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld. It was that very month that Rumsfeld went on to announce that “he expected America’s enemies would try to help terrorist groups obtain chemical and biological weapons” — echoing Patrick’s concerns of the previous decade. In late November, with Kadlec still in his ear, Rumsfeld and his Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz would draw up strategy for regime change in Iraq, and among the ideas they pondered to launch the effort included the US discovering “Saddam connections to Sept. 11 attack or anthrax attacks?” Indeed, though indirectly and often through hints and nudges as opposed to official statements from the executive branch, a group of Bush-era bureaucrats in Washington made this exact connection in the aftermath of Amerithrax and 9/11.

It was in this climate of mass paranoia and fear of an invisible enemy — be it terrorists in plainclothes or hidden anthrax spores — that the stockpile was expanded and funded with billions of taxpayer dollars. While several pieces of legislation increased funding for this pandemic response measure, the 2004 Project Bioshield Act most significantly authorized $5.6 billion for the «for the advanced development and purchase of security countermeasures for the Strategic National Stockpile (SNS)” — a gargantuan subsidization compared to Clinton’s 1998 legislation. And finally in 2006, the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act of 2006 established the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) to manage the stockpile. With the help of Kadlec, the legislation established BARDA within the ASPR, and made the new agency responsible for granting Big Pharma contracts to create medical countermeasures for pandemics and bioterror attacks (including countermeasures for the stockpile).

It was at Kadlec and company’s brainchild, BARDA, where Monarez entered the public sector in 2006, where she served under the leadership of Carol Linden, a scientist long embedded at the Pentagon who from 1979 through 2000 worked at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) lab in Fort Detrick as “Chief Research Plans and Programs” — overlapping with William Patrick III’s tenure at USAMRIID as its Plans and Programs Officer.

The following year in 2007, Monarez drafted the first ever HHS Public Health Emergency Medical Countermeasures Enterprise Strategy and Implementation Plan which, according to her LinkedIn, “defined the acquisition plan for the Department’s medical countermeasures program using the $5.6 billion Project BioShield Special Reserve Fund.”

In this capacity, Monarez shaped HHS funding for pandemic preparedness for years to come, subtly influencing the responses to future pandemics. She also codified a pledge that made clear what the nature of pandemic preparedness in a post-Amerithrax world would be; namely, a partnership between the world of academia/public health and the Pentagon:

“HHS [will] continue to coordinate medical countermeasure development and acquisition with DoD…”

One of the joint DoD/HHS ventures that this implementation plan set in motion was the funding of Ebola research and medical countermeasures for it. These funds trickled into several places; the USAMRIID lab in Fort Detrick, to members of the Viral Hemorrhagic Fever Consortium (VHFC) who worked at Fort Detrick — the organization which may have played a role in the 2014 Ebola outbreak — and the pharmaceutical company Gilead. Of the $1 billion that went into Ebola and Marburg virus research from 1997 to 2015, “public sources of funding invested $758.8 million” and “joint public/private/philanthropic ventures accounted for $213.8 million,” accounting for over 90% of total funds.

While the mainstream account of the 2014 Ebola outbreak postulates that the virus broke out zoonotically in Guinea, journalist Sam Husseini and virologist Jonathan Latham wrote a lengthy investigative report in 2022 arguing that the outbreak may have been the result of a lab leak from the VHFC’s only permanent lab in Sierra Leone. Since their report, the case for a lab leak has only become stronger as one VHFC member that has long researched the Ebola virus, Kristian Andersen, admitted that the VHFC lab in Sierra Leone was conducting Ebola research before the outbreak. While this had been suspected by researchers before, it had yet to be confirmed before Andersen’s claim.

If it is true that a leak from the VHFC Sierra Leone lab caused the 2014 Ebola outbreak, then some of the $5.6 billion in investments from Bioshield that Monarez helped define may have indirectly led to the devastation that occurred in West Africa that year. Monarez listed the Ebola virus as a top priority threat in her Implementation Plan, and defined antivirals, diagnostics and filovirus vaccines as the “projected future top priority medical countermeasure programs” to combat Ebola virus.

Based on accounts of Ebola researchers who were members of the VHFC and studied Ebola at Fort Detrick, the funding plan put forth by HHS had tangible effects for Ebola research. Former Fort Detrick scientist Thomas Geisbert, who in 2014 was selected as one of Time Magazine’s “Ebola fighters” of the year, has detailed how Fort Detrick received lavish funding for Ebola research as a result of post-9/11 and Amerithrax hysteria:

«[there] wasn’t money or interest or time to take those products across the finish line. “But after 9/11, everything changed. There was increased funding. It was fortunate for me, because Ebola was my main area of interest. When all the money became available, we started looking at developing a vaccine.»

This HHS funding was detailed further in the book, The Ebola Outbreak in West Africa by Constantine Nana:

«[Geisbert] has studied the Ebola virus for more than two decades and spent several years working with USAMRIID at Fort Detrick. In March of 2014, he was awarded (together with Profectus Biosciences, Tekmira Pharmaceuticals, and Vanderbilt University Medical Center) $26 million (to be distributed over five years) by the NIH to ‘advance treatments of the highly lethal hemorrhagic fever viruses Ebola and Marburg.’”11

Further, according to Crunchbase, a $15 million contract awarded to Tulane University by the HHS-housed NIAID created the VHFC, and thus led to the incarnation of the Sierra Leone laboratory as a permanent site of VHFC. Importantly, VHFC member Robert Garry is a professor at Tulane university. Just a year before the virus ravaged thousands of West Africans, Garry co-authored a paper on “a novel treatment for Zaire Ebola” along with eleven other authors who all hailed from USAMRIID at Fort Detrick. The study was funded by the Pentagon, including its Defense Threat Reduction Agency, which focuses on countering weapons of mass destruction.

In the aftermath of the outbreak, Andersen, Garry, and others would go on to issue articles that placed the origin of the outbreak in Guinea, providing a convenient scientific consensus for those handling Ebola research at the Sierra Leone lab. Yet, as Husseini and Latham noted, there was considerable overlapping authorship between these papers:

“One or more of just six researchers are represented on all of them: Robert Garry, Andrew Rambaut, Stephan Gunther, Kristian Andersen, Pardis Sabeti, and Edward Holmes are lead authors on almost all of these publications.”

Furthermore, “most of the senior authors of the phylogeny papers (notably, Robert Garry, Kristian Andersen, Pardis Sabeti, Erica Ollman Saphire, Daniel Park, and Stephen Gire) and plenty of less well-known authors, are directly connected to the VHFC and its Kenema lab. These authors in particular, have a career-sized conflict of interest, which they may also think is dwarfed by the possibility of being implicated in 11,000 deaths.” In other words, if the lab leak theory is true, then many of the scientists who penned the papers that allegedly proved the virus originated in Guinea had a direct conflict-of-interest in making those claims. As Husseini and Latham note in their investigation, these authors did not account for a plethora of evidence against a Guinean origin point in order to draw their conclusions.

Notably, Andersen, Rambaut and Garry later became some of the earliest peddlers of the theory that the COVID-19 pandemic emerged as the result of a zoonotic origin, as all of them co-authored the now notorious “The Proximal Origins of SARS-COV-2” paper in March 2020. The paper, published in the prestigious Nature scientific journal, downplayed the potential of a lab leak — a theory that has now become increasingly mainstream since.

Importantly, by virtue of their connections to VHFC and the consortium’s Ebola research, many of these scientists were targets of the government funding that Susan Monarez helped define in the post-9/11 construction of biosecurity infrastructure.

Where there is crisis, however, there is also opportunity. Monarez’s Implementation Plan also seems to have played a role in funding the drug that the pharmaceutical giant Gilead attempted, and failed, to make the antidote to Ebola — remdesivir, the antiviral medication now used to treat COVID-19.

Remdesivir emerged as the result of a collaboration between “Gilead, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID).” In 2009, developers saw the drug “as a potential treatment for hepatitis C,” but it unfortunately “didn’t work as hoped.”

Thankfully for Gilead, Susan Monarez was serving on the White House Ebola Task Force at the time of the outbreak in West Africa. There, she was responsible for “evaluating investments in Ebola-related pharmaceuticals and diagnostics.” It just so happened that the failed hepatitis C drug, remdesivir, would be one of the targets of these Ebola-related government investments.

According to Public Citizen, remdesivir’s potential as an Ebola countermeasure began when federal scientists screened “a thousand compounds from a Gilead library in search of a molecule to target Ebola virus.” They identified remdesivir as useful, and soon “U.S. Army scientists worked with the corporation to ‘refine, develop and evaluate the compound.’” This began a years-long public-private venture with the HHS, DoD and Gilead to bring remdesivir to market as a treatment for Ebola.

In 2014, the CDC, DoD and Gilead began “antiviral testing of remdesivir for Ebola and other viruses” and in 2016, the NIH and Gilead began “antiviral testing for coronaviruses and other viruses.” Yet the drug seemingly went nowhere, and by the second Ebola outbreak in 2019 a NIAID study showed the drug to be ineffective and it was ultimately dropped from the trial.12

Still, however, this public-private collaboration persisted. In 2020, the NIH funded “a multi-stage clinical trial of remdesivir for COVID-19” and the FDA issued an emergency use authorization for the unapproved drug, bringing it to market despite it still showing to be ineffective based on the results of a World Health Organization trial that found the drug did not “reduce mortality or the time COVID-19 patients take to recover,” a decision that reportedly “baffled scientists” who had been watching the trials unfold.

Even more oddly, the FDA never consulted the Antimicrobial Drugs Advisory Committee (AMDAC) to discuss the emergency passage of remdesivir. The AMDAC is a “group of outside experts that [the FDA] has at the ready to weigh in on complicated antiviral drug issues.” Had the FDA consulted this group, its representatives would have reviewed all available data on remdesivir and made a recommendation based upon it — yet at the time of remdesivir’s emergency rush to market, “it [had] not convened once during the pandemic.”

Nonetheless, the EUA paved the way for Gilead to rake in $873 million from remdesivir sales, topping Wall Street estimates at the time by over $100 million.

Yet another interesting investment that the White House made during the Ebola response period was a vaccine candidate developed jointly by National Institute for Allergies and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and a subsidiary company of the pharmaceutical giant Glaxosmithkline. This candidate, called the ChAd3 vaccine, underwent trials at a few institutions, one of them being the Oxford Jenner Institute, and received €200 million in funding from an organization known as the Wellcome Trust.

The Wellcome Trust and the Jenner Institute are intimately linked as Unlimited Hangout has previously reported — most directly through the funding Wellcome provides the Institute. Also, the Jenner Institute’s director since 2005, Adrian Hill, leads a research group at the Wellcome Trust, and previously helped found the Wellcome Trust’s Center for Human Genetics.

The Wellcome Trust, notably, has deep ties to the eugenics movement via its connections to the organization formerly known as the British Eugenics Society, now called the Adelphi Genetics Forum, as multiple members of Adelphi’s governing board hail from the Wellcome Trust. Furthermore, when Wellcome set up its Contemporary Medical Archives Centre, the first organizational archive it acquired was that of the Eugenics Society. The records contain “a good deal of material on subjects such as the treatment of the mentally and physically defective, the development of birth control methods, the legalisation of sterilisation, [and] the use of artificial insemination…”

Francis Galton, the godfather of eugenics who “constructed a racial hierarchy, in which white people were considered superior,” was described rather uncontroversially by the Adelphi Genetics Forum as an “eminent late nineteenth century polymath.” This may be due in part to the fact that Galton was the honorary president of the first incarnation of the Eugenics Society/Adelphi Genetics Forum, according to A Life of Sir Francis Galton: From African Exploration to the Birth of Eugenics.13

Furthermore, Adrian Hill — the director of the Jenner Institute and a Wellcome employee — has an early connection with a longtime associate of the Eugenics Society, the late David Weatherall. Weatherall was Hill’s doctoral advisor, and had a lengthy history with Walter Bodmer, the man who made the first proposal for The Human Genome Project in 1986, and at that point had already been a decades-long affiliate of the Eugenics Society. Weatherall’s work was being funded by Bodmer around 1989, and this relationship persisted for decades after. During the period that Bodmer was president of the Eugenics Society (then called the Galton Institute) from 2008-2014, Weatherall spoke at one of their conferences in 2014. Furthermore, in 2008, the same year Bodmer became president, Weatherall joined Bodmer as a speaker at the Galton Institute centenary symposium — celebrating “100 years of medical genetics.”

While the Glaxo-Jenner vaccine never came to fruition, the Jenner Institute would go on to develop a vaccine in collaboration with AstraZeneca for COVID-19 a few years later. That vaccine was brought to market via emergency use authorization, and was heralded as the vaccine for low- and middle-income countries during the pandemic, as it was cheaper to develop and easier to store than its mRNA alternatives. Yet the vaccine’s use was eventually halted in multiple countries after “fears the shot may have caused some recipients to develop blood clots,” and was eventually withdrawn by AstraZeneca entirely.

Importantly, the precedent regarding the authorization of the unapproved AstraZeneca vaccine to market had been partially established back during the 2014 Ebola outbreak. In the heat of Ebola ravaging West Africa, the Glaxo vaccine — which Monarez’s funding targeted — was rushed to trials in an “unprecedented” way. As Science reported, the early injection of the Glaxo vaccine into humans was an “extraordinary, unprecedented gamble” because of how quickly the process was moving. “Normally, vaccines take many years to advance from small phase I studies, which look at safety and immune responses,” the journal stated. From there, they move to“phase II studies, which do the same in larger groups; to phase III, in which efficacy is tested in large populations at risk of the disease. An earlier WHO consultation made the startling announcement on 5 September that this crisis required compressing the timeline, which effectively does away with traditional phase III studies” (emphasis added).

Furthermore, Jeremy Farrar, who at the time headed the Wellcome Trust, advocated for a “step-wedge trial” to avoid a randomized control trial. The step-wedge, notably, automatically gives every study participant the vaccine (just at different times). Yet this tactic “makes it more difficult to control for biases like differences in rates of new infection, behavior, and availability of protection suits” — thus making the trial less objective and its data less indicative of the vaccine’s efficacy. Farrar’s advocacy here is unsurprising; this kind of disregard for thorough and long testing of drugs pervades the Wellcome Trust. The organization has since pursued projects that seek to use lab-grown human organs to test pharmaceutical products on to replace animal trials altogether.14 Nonetheless, this acceleratory attitude still could not achieve the task of getting the Glaxo vaccine to market.

Despite the failure of the Glaxo-Jenner Ebola vaccine, however, remdesivir was not the only drug that made Big Pharma massive profits as a result of Monarez’s 2014 Ebola Task Force funding. The rest of her investments, such as vaccines from Johnson & Johnson and Merck, as well as monoclonal antibody treatments from Regeneron and the DoD-funded Mapp Biopharmaceutical Inc., would come to fruition in 2017 when they were added to the Project Bioshield stockpile with an investment of $170.2 million. It was a full decade earlier that Monarez penned the HHS Investment Plan to allocate $5.6 billion in BioShield funds across the public and private sectors, including for vaccines and antivirals against the Ebola virus. More than ten years later, after working in two different government offices since her time at BARDA, she’d completed a critical funding component of that Implementation Plan. It took, however, a potential lab leak, a deadly epidemic and bringing an unapproved drug to market, to achieve this goal.

Monarez’s role in the Ebola response, however, was likely not limited to her influence on drug investments. Her Linkedin states that she was an «instrumental member” of the Task Force, “responsible for developing the Nation’s public health response plans to the Ebola outbreak in West Africa…” Beyond pharmaceutical investments, the nation also embarked on a massive biosurveillance campaign to monitor the outbreak of the virus.

Much of the technology deployed to surveil and combat the Ebola virus in this period — by both private contractors and the Pentagon — would later be deployed, and likely refined beforehand, during the COVID-19 pandemic. The U.S. Government’s Ebola surveillance operation utilized a form of digital surveillance reliant on collecting a vast array of data from different sources in order to string together those broad samples into a precise narrative, such as where Ebola might potentially break out, and where a particular strand’s origins might trace back to. This form of surveillance is an age-old method of the national security state, and its implementation into the public health/pandemic preparedness model is not something that has occurred in parallel to national security usage, but in symbiosis with it.

For example, the Ebola Task Force issued $60 million to the Pentagon to create a Cooperative Threat Reduction program to “address urgent…biosurveillance needs in the three countries most affected by the Ebola outbreak.” The DoD addressed these needs at least in part by repurposing a system traditionally used to detect weapons of mass destruction to “instead flag the onset of Ebola outbreaks.” The system, which in 2014 was described as a “next-generation information gathering, sharing, analysis, collaboration and visualization system” harvested “data of interest across the military and intelligence communities.” Its name, complimenting its multi-source data harvesting likely picking from satellite imagery, social media data, phone call locations, medical records and more, was “Constellation.”

Assistant secretary of defense for Nuclear, Chemical and Biological Defense Programs Andrew C. Weber touted Constellation in 2014, advocating for “a shared biosurveillance system that integrates local disease information, civilian disease information and DoD information about its own military forces.” He also called for the use of information technologies such as social media to enable “real-time disease detection that allows countries to prevent outbreaks or contain them.”

Constellation quickly developed into a public-private partnership used by “nongovernmental organizations, governments most affected by the Ebola outbreak, and Defense Department laboratories involved in the outbreak response,” expanding its use, and likely the data the program could aggregate and analyze.

Another biosurveillance operation that was being used during the Ebola outbreak was the GDELT Project database, which, according to Defense One, once competed for funding from the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Agency (IARPA). Supported by the Google incubator Google Jigsaw –– a client of Antony Blinken’s consulting firm WestExec –– during the 2014 outbreak, GDELT claimed that it predicted an Ebola outbreak based on “a French language newswire article that observed, amazingly, not the keyword Ebola but ‘a disease whose nature has not yet been identified has killed 8 people in the prefecture of Macenta in south-eastern Guinea … it manifests itself as a hemorrhagic fever…’” Interestingly, the following year in 2015 Google Jigsaw was working with the State Department to “identify Google users interested in Islamic extremist topics” in order to de-radicalize them, engaging in “digital counterinsurgency.” In 2012, they were working with Hillary Clinton to oust Bashar al-Assad from power in Syria. 15

While it is not clear in what way the Peter Thiel-founded mass surveillance company Palantir aided the government response to the 2014 Ebola outbreak, the company has touted its role in “countering Ebola” with the CDC in two different press releases. These press releases state that this partnership took place not long after Palantir and the CDC “initially partnered,” implying that the Ebola outbreak may very well have been one of Palantir’s first forays into a real pandemic biosurveillance scenario.

During the Ebola outbreak, the CDC conducted a direct biosurveillance effort in West Africa in which they tracked the “approximate locations of mobile phone users” who dialed emergency call centers in order to predict outbreaks before they occurred and where they might spread.16 It is unclear whether or not Palantir aided this effort, though the program is strikingly similar to past Palantir projects. Yet, in whichever capacity the surveillance contractor aided the Ebola response, Monarez was not far from it.

Since then, via massive government contracts across HHS agencies, as well as former Palantir employees being installed at HHS, the company has become a vital component of the US government’s biosecurity infrastructure.

Before Monarez served in the White House, however, she joined the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in 2009 and would remain there until 2013. There, she was the Branch Chief and Chief Science Advisor of the Homeland Security Advanced Research Projects Agency (HSARPA) where she reported to biosecurity veteran, Tara O’Toole.

HSARPA, DHS and Tara O’Toole

Tara O’Toole is perhaps best known for writing a pre-pandemic disaster simulation of a smallpox bioterror attack just months before Amerithrax seeded a deep sense of paranoia and pro-war fervor into American consciousness. The simulation was conducted at the Andrews Air Force Base in Washington, D.C. and was in part presented by the Johns Hopkins Center for Civilian Biodefense Studies, which O’Toole was the director of at the time. It was ominously titled “Dark Winter.”

While O’Toole chose smallpox as the pathogen that would infect Americans in her simulation, the exercise eerily predicted key elements of the actual anthrax attacks that occurred only months later.

As occurred in the real attacks, O’Toole’s script had threatening letters delivering to prominent members of the American media class, and predicted that such an event would transform the public’s affinity for peace into a thirst for revenge. Perhaps most importantly, Dark Winter established the narrative that Al Qaeda and Iraq were working as partners to carry out these attacks.

The simulation began with a geopolitical context briefing which contained a section titled “Suspected Bioweapons Production – Iraq,” in which it suggested that Saddam Hussein was using a vaccine plant as a front for bioweapons production, as Hussein had “imported equipment and materials that might be used to build chemical or biological weapons.” Later in the simulation, the National Security Council in Dark Winter deduced that the bioterror attack was “related to decisions [the U.S.] may make to deploy troops to the Mid-East.” Further, in one of the exercise’s fictional news reports, the reporter claims that “Iraq might have provided the technology behind the attacks to terrorist groups based in Afghanistan.”

As Robbie Martin and Abby Martin recounted in their audio documentary, Schrodinger’s Super Patriots: The 2001 Anthrax Mystery, multiple participants of the Dark Winter simulation as well as officials adjacent to them went on to make conspicuous connections between the 9/11 attacks, anthrax and Iraq. These included Dark Winter participants James Woolsey and Jerome Hauer, Bush official Richard Perle, and Dark Winter participant/disgraced New York Times reporter Judith Miller. Miller later released a book at the beginning of Amerithrax hysteria that, according to Whitney Webb, “asserted that the U.S. faced an unprecedented bioterrorism threat from terrorist groups like Al Qaeda and [nation states like] Russia.” In their audio documentary, the Martin siblings also dug up a slew of old news reports from the time citing anonymous U.S. government officials suggesting a connection between the anthrax attacks, 9/11, Al Qaeda and Iraq — eerily echoing the simulated predictions of O’Toole’s Dark Winter. Later, the anthrax used in those attacks was found to have originated from strains held only by the U.S. military.

Given the proximity of O’Toole’s Dark Winter simulation to the Bush administration, and the ways in which it seemed to inspire the P.R. tactics the administration later employed in response to the anthrax attacks, the question has been raised as to whether or not someone who attended the Dark Winter simulation — or was familiar with the fictional trajectory it laid out — was the person who reportedly instructed Dick Cheney’s staff to begin taking Cipro, the antibiotic used to combat anthrax infection, the night of the 9/11 attacks. Based on this seemingly prophetic suggestion, it appears that this person had foreknowledge of the anthrax attacks. The prospects of this possibility become even more worth considering given that, as reported by The New York Times Magazine, O’Toole herself attended a meeting with Dick Cheney just days after 9/11 with former Air Force colonel, Dark Winter author and colleague of Robert Kadlec, Randall Larsen, in which they stressed that the U.S. was underprepared for a biological attack. To make this point, Larsen allegedly smuggled a sample of weaponized Bacillus globigii into the meeting, which is “almost genetically identical to anthrax,” in order to demonstrate the lack of government security surrounding bioweapons.

A few years later in 2009, shortly after Barack Obama became president, O’Toole went on to become the Under Secretary of Science and Technology (S&T) at DHS, “the principal adviser to the Secretary on matters related to science and technology.” It should be noted that the tenures of both Monarez and O’Toole at DHS seemingly overlap perfectly with each other, both joining the agency in 2009 and leaving in 2013. The two worked closely together, as Monarez played a significant role in allocating funds for HSARPA. HSARPA reports directly to the Undersecretary of S&T, which at the time was O’Toole.

An integral part of O’Toole’s focus during her time at the agency was the development of “Apex initiatives” which “pioneered new partnerships between S&T and DHS operations, and successfully delivered innovative technologies to meet DHS’ urgent operational needs, including the use of advanced ‘Big Data’ analytics by ICE.” ICE notably bought Palantir software during O’Toole’s tenure allegedly in order to track down and take “revenge” against drug cartel members who murdered an ICE agent in Mexico.

Another part of O’Toole’s reforms involved shifting most research and development (R&D) within S&T to HSARPA, making the agency encompass “the vast majority of the R&D activities in the S&T Directorate.” This change obviously made Monarez’s role vital to the S&T directorate. According to her LinkedIn profile, she was overseeing $300 million in federal contracts — presumably funding the majority of the entire directorate’s research.

Monarez utilized these funds for research of border-security and counterterrorism technology. One of the most startling programs injected with this money appears to have been the testing of a “real-time malintent detection capability” called Future Attribute Screening Technology (FAST). Reveal News described this malintent detector as “machinery that can measure things like heart rate, micro-facial expressions, breathing patterns and body heat as an individual walks through a security portal.” Using the data harvested from this technology, software algorithms would then “determine if a combined set of behaviors and physiological qualities amounted to someone hiding plans to carry out a terrorist attack.”

According to National Defense Magazine, during a testing of the technology in 2009, “a laser measured [participants’] heart and respiratory rates, an eye tracker measured their blink rates and pupil dilation, a thermal camera measured the heat on their skin and a reconfigured Nintendo Wii Balance Board measured their fidgeting. Nearby computers processed the data, and the system’s software recommended to the security guard which participants should be taken aside for follow-up questioning.”

In a 2011 DHS budget paper, the agency claimed that, in 2009, they “demonstrated a real-time malintent detection capability at a simulated speaking event using indicators such as heart beat, respiration, and pore count to develop a screening facility and a suite of real-time, non-invasive sensor technologies to rapidly, reliably, and remotely detect indicators of malintent.”17 In 2011, notably, HSARPA was building on the FAST project to include “passive stimuli” in its screening procedures in order to better detect malintent.

Monarez also seems to have funded a Lockheed Martin-partnered border-security program called the Tunnel Detection Project –– an invasive surveillance effort to utilize “ground penetrating radar” to construct digital images of underground tunnels. The project was meant to provide DHS with the surveillance capacities to detect tunnels built by criminals for the illicit trafficking of drugs, humans and other contraband.

HSARPA scanned these tunnels using “radar antennas in a trailer…towed by a Border Patrol truck.” The antennas shot “a signal directly into the ground and [used] it to construct a multi-colored picture of the earth.” In 2011, National Defense Magazine reported that DHS and the Pentagon were deploying “sensors and robots” in the Southwest to detect and map out “illegal tunnels being built underneath the U.S.-Mexico border.”

Monarez left the agency in 2013 and returned to DHS three years later after her stint in the White House, this time as the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Strategy and Analysis. There, she chaired a DHS Technical Advisory Board and served as a member of the Homeland Security Advisory Group — influencing policy and resource planning of DHS’s “$2 billion science and technology portfolio.”

Notably, in DHS’ 2017 budget proposal, the S&T Directorate requested “$94.9 million for R&D on Biological and Chemical Capability for the BioWatch program including S&T funding to test and identify technology enhancements to the existing operational system” (emphasis added). The BioWatch program is a public-private national biosurveillance effort that “provides early warning of a bioterrorist attack in more than 30 major metropolitan areas across the country” that is managed by the DHS Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Office. The effort “involves a large network of stakeholders” from a myriad of industries, including law enforcement, “who collaborate to detect and prepare a coordinated response to a bioterror attack.” Among Biowatch’s present goals are “providing real-time data across the Homeland Security Enterprise” and “improving information-sharing between federal, state and local operators.”

It has worked to achieve these goals in part by developing “autonomous biodetection instruments” with aerospace defense contractor Northrop Grumman. The autonomous instruments operated “24 hours per day, 365 days per year” and utilized bio-detectors placed in U.S. population centers to “continuously monitor the air for agents of biological concern” — providing DHS with a constant surveillance-based early detection system.

Monarez’s influence on a DHS budget portfolio that funded efforts such as this seemingly foreshadowed a later career move she would make — that which she is now most known for. In 2022, Monarez became the first official Deputy Director of ARPA-H, where she would spearhead the development of invasive biotechnology ripe with mass surveillance potential. In addition, ARPA-H’s origin story as a predictive crime “mental health” detector turned biotech procurement program sheds light on the symbiotic relationship between the technocratic nature of modern public health infrastructure, and the dystopian national security-based system of mass surveillance that continues to expand globally. Monarez’s roots, as well as her time at ARPA-H, make clear that virtually her entire career has existed at the cutting edge of this intersection.

ARPA-H

While ARPA-H was established under the Biden administration, it was initially pitched to Donald Trump during his first term. In the aftermath of two mass shootings that left 31 people dead in their wake, the ARPA-H sell to the Trump administration included a program called “Safe Home,” or Stopping Aberrant Fatal Events by Helping Overcome Mental Extremes.

Though the concept of a “health” focused iteration of DARPA –– conceived of and lobbied for by the Suzanne Wright Foundation –– was originally meant to be a “project to improve the mortality rate of pancreatic cancer through innovative research to better detect and cure diseases,” this new proposal to the Trump administration highlighted a different, less obvious, function of the program.

As The Washington Post described it, the program would utilize “volunteer data to identify ‘neurobehavioral signs’ of ‘someone headed toward a violent explosive act.’” A person familiar with the discussions surrounding ARPA-H told WaPo something eerily revealing regarding the true nature of ARPA-H: “There is no doubt that addressing this issue helps the president deal with two issues he has to find real success on: one is the health-care front and one is the gun-violence front.” This account implies that no matter what pretext the predictive medicine-focused ARPA-H would be launched under, its purpose going forward would always remain dual-use: both for “health” and national security.

Indeed, while Safe Home has not been outwardly pursued by ARPA-H, Monarez has since made it clear that one of her primary objectives at the agency was something similar. In an interview with One Mind, Monarez asked “What can we do through all of this harnessing of the data that has been generated for decades and decades, and it’s dispersed in so many different places?” With “generative AI capabilities,” she continued, we can “combine all of that [data]” to replace in-person mental health screenings of patients presumably with AI-generated ones instead — utilizing a myriad of datapoints about a patient to diagnose and treat them for a host of mental conditions, as opposed to the in-person guidance and analysis of a real doctor. This, Monarez said, will conveniently bring traditional medical experience “to the home,” providing “empowerment” to patients dealing with the “prohibitive” problems of “mental health issues.”

At the time Monarez made these statements, she was serving as Deputy Director of ARPA-H. A press release announced her selection as Deputy Director of ARPA-H in January 2023 and noted that she would work under the leadership of director Renee Wegrzyn, a former program manager in the DARPA Biotechnologies Office. In this role, Monarez shaped “the strategic vision” and executed the agency’s programs, and also oversaw “the development and management of groundbreaking health research initiatives.” She also worked with “multidisciplinary teams” to “evaluate and select” research proposals for ARPA-H to tackle. Furthermore, she fostered “strong partnerships with leading academic institutions, industry stakeholders, and government agencies to leverage expertise and resources for joint research efforts.” In other words, Monarez shaped much of ARPA-H’s catalogue of biotechnology research and development, and directly worked with contractors and “stakeholders” to facilitate the execution of these projects.

Yet, to totally understand Monarez’s objectives and role at ARPA-H, the dual-use nature of the agency itself — as well as Monarez’s work at DHS — must be considered when analyzing the programs she helped select and execute.

ARPA-H’s REACT program, for example, is currently developing two chips that would be surgically implanted into patients during surgery that would “interface with a simple software platform or app that allows users to track their condition directly.” One chip would act as a “Living Sentinel” that would mine patients for data to track “key bio markers” in order to identify “markers for disease.” The other chip would act as a “Living Pharmacy” to deliver “therapeutic molecules” to patients on demand — leaving medicine intake, and presumably medical advice regarding drugs, up to AI technology. The REACT program manager previously worked at DARPA in the same position within the Biological Technologies Office. Before DARPA, he was at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory working as the head of “surface nanoscience and sensor technology.”

To pursue this project, ARPA-H awarded millions of dollars to different “teams” at different institutions each focused on developing specific parts of the treatment technology. The institutions awarded contracts were the Mayo Clinic, Carnegie Mellon University and Columbia University.

Notably, Carnegie Mellon University was established by the steel tycoon Andrew Carnegie in 1900 — the same man that was the head of the Carnegie Institute of Washington which Charles Davenport persuaded to establish his Eugenics Records Office at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.18 To work on REACT, Carnegie Mellon University brought in through a subcontract an external company to aid their research effort; Ginkgo Bioworks, a partner of the World Economic Forum that is primarily funded through an investment firm controlled by Bill Gates. Considering Monarez’s role in fostering “strong partnerships” with outside collaborators at ARPA-H — as well as Renee Wegrzyn’s, the ARPA-H Director whom Monarez worked under, previous role as vice president of business development at Ginkgo — it is very possible that Monarez played a role in cultivating this partnership.

Indeed, REACT is not the only partnership involving Ginkgo Bioworks and ARPA-H. Since Monarez left the agency to head the CDC, the agency has granted $29 million to a Ginkgo-led consortium to create “new and efficient biomanufacturing processes to strengthen pharmaceutical supply chains” utilizing “wheat germ cell-free expression systems.”

The joint venture is aimed at “improving the speed, scale, and access to medical treatments and enhancing health security in the US,” echoing the rhetoric of the ARPA-H program CATALYST which seeks to accelerate the time from which drugs are developed to when they’re brought to market. This is important to note in this context, as even though this Ginkgo partnership was established after Monarez left ARPA-H to take up her role as the interim Director of the CDC, her LinkedIn states that she shaped “ARPA-H’s future research agenda by identifying emerging trends and gaps in health innovation.” One of these “gaps,” based on this partnership and other ARPA-H projects, appears to be the lack of regulatory and manufacturing infrastructure that would enable drugs to be rapidly brought to market. The procurement of a more “accelerated” development-to-market paradigm is a major objective of the biotechnology industrial complex, which often suffers substantial losses within the current regulatory framework.

Yet this relationship between Ginkgo and ARPA-H warrants mentioning for the links it creates to another network deeply entrenched in the biosecurity apparatus — Palantir, and more broadly the “Thielverse.” Multiple members of Ginkgo’s board of directors are tied to Thiel’s sprawling business and investment empire.

Board member Ross Fubini, for example, founded a venture capital firm that invested heavily in the Thiel-backed AI defense contractor Anduril, founded by Oculus founder and Thiel Fellow Palmer Luckey. Beyond this, according to Forbes, Fubini has “solo invested” in as many as 15 Palantir alumni startups which “propelled [him] onto all three annual editions of the Forbes Midas Seed List of the world’s top earliest-stage investors.” Rubini’s Anduril investment is «now worth tens of millions at Anduril’s most recent valuation, enough paper gains to return its first fund several times over.”

Fubini’s induction into this network of Palantir associates continued to grow after his backing of Anduril. In 2020, Fubini invested in a “Medicare-focused” startup called Chapter, and soon after, “two of Chapter’s three biggest partner institutions” hopped on the fundraising train — Peter Thiel himself, and JD Vance’s Narya Capital.

However, Fubini’s connections to Palantir actually date back to 2006, when he introduced “Palantir’s first business hire to its first engineer.” That engineer was Akash Jain, “a former colleague of Fubini,” who is now the CTO of Palantir government business. The business hire, meanwhile, was Shyam Sankar, who is now the CTO and Executive Vice President of Palantir — and who also serves on the board of directors of Ginkgo Bioworks with Fubini. At Ginkgo, Sankar is the Nominating and Corporate Governance Committee Chair, meaning Sankar plays a significant role in selecting who is on the board. Sankar’s influence appears prevalent, as Fubini and him are not the only Thielverse associates at Ginkgo.

Another board member is Christian Henry, who was previously the COO and CFO of the biotechnology company Illumina. Though Henry is no longer part of Illumina governance, he is still a major shareholder of the company. Recently, Illumina partnered with DNA test company Nucleus Genomics which is currently “realizing the dream set into motion long ago by The Human Genome Project” with its application that “harnesses the power of whole-genome sequencing.” Two years before this team-up, Nucleus raised $14 million in funding from a group of investors that included Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund.

And finally, there is Sri Kosuri on Ginkgo’s board of directors, who is the CEO of the fin-tech company Octane — which has been financed to the tune of $50 million by Peter Thiel’s Epstein-funded Valar Ventures.

Yet ARPA-H also boasts more direct ties to Palantir, as Palantir runs the agency’s core data infrastructure, enabling ARPA-H to “rapidly collect, synthesize, analyze, and make decisions from a range of data sources…” This closeness to Palantir –– a company built on the practice of making the retrieval and analysis of data from disparate sources seamless –– should also be considered as we examine more of ARPA-H’s projects, which mine bio-data under the pretext of health and wellness.

One of these programs harkens back to the HSARPA tunnel-penetrating technology that was worked on during Monarez’s time at DHS. Yet, rather than scanning and building three dimensional constructs of tunnels, this ARPA-H project seeks to scan and construct digital models of the human body. Called PSI, it aims to create detailed imaging technology capable of generating images of “hard-to-see nerves, blood vessels, and other structures, even if they are buried under other tissue” in order to provide 3D visualization of “critical anatomy” during surgery.

The ARPA-H program INDEX, meanwhile, focuses on how images generated by imaging technology (such as that which PSI aims to create) can be stored and harnessed for later use. INDEX is based on the premise that AI and machine learning algorithms currently lack the imaging data required to sufficiently train their models. This apparently leaves huge medical potential untapped, as the program claims that these algorithms “can help radiologists and pathologists make faster and better diagnostic decisions.”

INDEX provides a solution to this problem. It aims to create a massive, easily accessible bank of imaging data that links “data providers, data users and service providers with high quality images” to enable “AI tool development for pathology and radiology.” The range of data it seeks to provide will be vast, as the program aims to “increase the number, type, and quality of images available for machine learning models, as well as boost geographic, racial, and ethnic diversity of images.”

Interestingly, ARPA-H recognizes the regulatory hurdles of accumulating this sprawling dataset, and is already collaborating with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to “reduce barriers in obtaining data needed for INDEX.” It is likely that Monarez worked directly on diminishing these regulatory obstacles restricting the program’s aspirations of unfettered data access. According to her LinkedIn, at ARPA-H she provided “strategic guidance on regulatory and go-to-market matters, working closely with FDA, CMS, external investors and other stakeholders.”

Just as ARPA-H’s dual-use nature places the beneficial and convenient aspects of the program’s biotechnology development into a larger context, INDEX places programs such as PSI into a broader one as well. While enhanced imaging data could presumably have immediate positive effects during surgical operations, programs such as INDEX raise important questions; will those images be stored in databases? Will they be utilized later, and by whom, and for what purposes?

Just recently, the vast Center for Medicaid Services (CMS) database with information on more than 140 million Americans was handed over to ICE, the Palantir-powered deportation authorities. ICE is currently constructing a master database, reportedly with Palantir, to collect data from a myriad of sources to carry out their deportations. Among other agencies such as the IRS, this “master database” will also pull information from HHS — the parent agency of ARPA-H, and the CDC. So, more specifically; will data from programs like INDEX be utilized for purposes beyond public health?

Virtually all of ARPA-H’s catalogue of programs raises the same question. From PARADIGM, a project that seeks to use patient location data collected via satellite to build a de facto portable hospital system, to OCULAB, which aims to harness wearables to constantly scan patient “biomarkers,” specifically in the tearduct, to predict disease before onset, to PRINT, which seeks to utilize a massive database of genetic information to print vital organs for patients, to RAPID and POSEIDON, which plan to expand at-home COVID-19-style diagnostic testing to other conditions such as cancer — all of these programs, beyond their direct medical potential, pursue innovative methods of biodata collection.

POSEIDON seeks to integrate at-home cancer screenings “securely with electronic health records.” RAPID’s pursuit of AI technology capable of detecting rare diseases at home prioritizes “data interoperability and integration into existing clinical workflows” in order to ensure “scalability across healthcare organizations.” In order to enable this AI technology to make its diagnoses, it “aims to integrate data from a fragmented landscape” in order to construct “the largest curated dataset of…rare disease patient data…” The very premise of PRINT, which plans to utilize a biodata bank to print organs, would inherently require a vast amount of detailed genetic data to achieve its goal. Will the biomarkers that the wearables in OCULAB scan for also be used to train the AI-diagnostic tools it relies on? It is hard to imagine a scenario in which it would not.

This question of data privacy becomes all the more important when contextualizing all of these programs in the background of ARPA-H’s BDF Toolbox — a project that seeks the unification of disparate health datasets, making vast amounts of data readily available by making it interoperable.

The program page remarks that all the research health datasets spread out around the medical field “could be so much more useful when pooled together…” Yet, privacy restrictions and dated technology that use “different platforms to store different datasets” make this goal difficult. The BDF Toolbox aims to solve this problem by making “it easier to connect biomedical research data from thousands of sources and overcome barriers caused by incompatible data dialects” through methods such as “lower[ing] barriers to high-fidelity timely data collection in computer-readable forms” and “improving stakeholder access while maintaining privacy and security measures.” How the program will “lower barriers” to obtaining and collecting this data while at the same time “maintaining privacy” measures is not specified.

The Toolbox also seeks to make this data integrable, presumably into both research and maybe even government policy, as the program page states that the technological innovations it plans to make will “reduce the time needed to integrate new data sources, and improve data usability by community members across disciplines and biomedical literacy levels.” Furthermore, the analysis and integration of this data will be conducted not only by humans but by AI algorithms, and fed into machine learning programs. Whether by human or AI, the Toolbox enables the harnessing of data from “thousands of labs, hospitals, and centers…”

The concept of the BDF Toolbox — creating a single location for vast amounts of data to be stored — is not a new one. It harkens back to Charles Davenport’s Eugenics Records Office and to the George W. Bush-era pre-crime Total Information Awareness program that sought to funnel huge amounts of data into a single, “ultra-large-scale’ database.” Most recently, this type of effort can be seen in the formerly Elon Musk-led Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) objective to construct a “mega-API” that can access huge swaths of data by making “software systems talk to one another.” This DOGE effort is carrying out an executive order from President Trump to “eliminate information siloes.” Importantly, the company that the Trump administration turned to to build out this mass surveillance infrastructure was Palantir — the same company that runs ARPA-H’s core data infrastructure.

These partnerships, as well as the simultaneously occurring efforts to expand data sharing, cast serious doubt on ARPA-H’s claimed commitment to privacy rights. Furthermore, Monarez’s essential role in the development of these programs, contextualized with her layered history within the biosecurity apparatus, suggests that she will take the CDC — which is currently already building out a massive biosurveillance program with Palantir — even further into the shadowy world of surveillance and militarized science.