In the roughly two years since Jeffery Epstein’s “suicide” in a Manhattan jail cell, some of his closest associates, friends, and “clients” continue to scramble to salvage their carefully crafted public images from the fallout of having had links to Epstein and/or the network that enabled his sex-trafficking and blackmail activities. Chief among those who have labored to keep their names out of the press is arguably Epstein’s closest associate alongside Ghislaine Maxwell, the retail billionaire Leslie Wexner.

Wexner, the richest man in Ohio, has had his well-crafted public persona irrevocably tarnished by the association, but he has used his influence and power to keep his name largely out of the press, despite the clear ties between him and Epstein as well as the many sordid acts that are now synonymous with Epstein’s name.

One obvious consequence of keeping Wexner’s name mostly out of the headlines has been a lack of journalistic scrutiny applied to his dealings, both past and present. While some Ohio journalists, Bob Fitrakis chief among them, have critically reported on Wexner for decades, there has been little attention given to the dark underbelly of Wexner’s empire by the mainstream press, despite his obvious and extremely close connection with Jeffrey Epstein.

There are several historical moments when Wexner’s made-to-order persona of the “rag trade revolutionary” unravels, with the most critical being the murder of Arthur Shapiro and its subsequent cover-up. While some mainstream outlets, such as the Daily Beast, have recently attempted to dig slightly deeper into Shapiro’s death and what it reveals about Leslie Wexner, in this article reveals previously unreported implications of Shapiro’s death and how it relates to the billionaire who was Epstein’s most obvious, yet unindicted, accomplice.

The following article is adapted from a chapter on Leslie Wexner from my upcoming book One Nation under Blackmail. You can preorder the book, due out in early 2022, from TrineDay (the book’s publisher), Amazon, or Barnes & Noble.

The Hit

In March 1985, Arthur Shapiro, a lawyer in Columbus, Ohio, was murdered in broad daylight. Per police reports, he had been eating breakfast in his car with an unidentified man. Shortly after 9:30 AM, Shapiro sprang from his car with the unknown man also abruptly leaving the vehicle, giving chase. The man fired his handgun at Shapiro, grazing his hip and arm, before Shapiro reached a condominium and began pounding on the door. The unidentified man, described as wearing all black and running with a limp, then shot Shapiro twice in the head at point-blank range before fleeing the scene in Shapiro’s car. The car was found the next morning in a mall parking lot. It had been wiped clean of fingerprints. The killing was regarded by police as a professional hit and likely tied to organized crime.

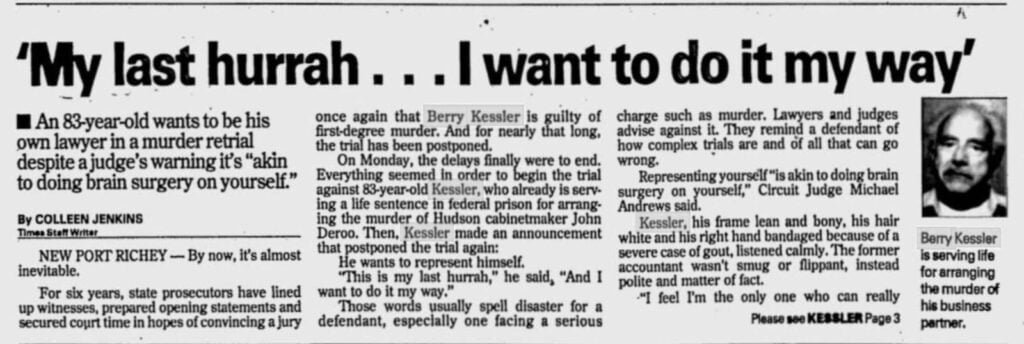

Local authorities suspected at the time that Shapiro’s murderer may have been hired by Columbus-based tax accountant Berry L. Kessler. Two of Kessler’s then employees “later” alleged to the Columbus Dispatch that they had seen a man matching the killer’s description visit Kessler’s office the day after the shooting and that they had seen Kessler counting a large pile of money before this man had arrived. Since the killer’s description was mainly based on his clothing, however, it means the killer showed up to receive a presumed payment for a contract killing in the same attire in which he had committed the killing a day earlier, which seems unlikely given the professional nature of the hit and hitman per the police. It is also not clear how long after the murder these former employees of Kessler relayed this information to the Dispatch, but other Dispatch reporting suggests that such claims were not made until many years later, in the early 1990s, when Kessler was arrested for a contract killing that also involved the FBI.

In 1991 Kessler was charged in Florida with arranging the slaying of a business partner, John Deroo. He was convicted of that crime in 1994 and died in prison in 2005. Kessler was caught in the Deroo case through information provided by an FBI informant, which led to Kessler’s attorney arguing that Kessler had been “tricked by a government informant into complicity in a criminal act.” Per a Columbus Dispatch article entitled “Informant Led Way in Florida Arrest,” it was only when Kessler was charged in connection with Deroo’s slaying in 1993 that he became the “prime suspect” in the Shapiro case, though he had initially been a suspect but was never charged in connection with that murder. Police later stated that no suspect in the Shapiro murder had ever been eliminated from their suspect list.

In 1986, however, Kessler was convicted along with two co-conspirators of having helped Arthur Shapiro file false tax returns. Shapiro, shortly before his death, had been named an unindicted co-conspirator in the same tax case and was due to testify the day after he was killed.

As an unindicted co-conspirator, Shapiro would not have been indicted himself, but he could have provided damaging information regarding those who had been indicted, giving considerable motive to Kessler and the other co-conspirators—unnamed in the Dispatch or other media reports at the time—to see that Shapiro did not testify. What is odd about this court case, beyond the significant fact that a key witness had been shot in what police referred to as a “mob style murder” or “mafia hit,” is that Kessler and his co-conspirators were only sentenced to probation and did not serve prison time for the crime of helping Shapiro file false tax returns in 1971 and 1976.

This raises several questions: Why was Shapiro an unindicted co-conspirator if he was the one who filed the fraudulent tax returns, while those charged were convicted of aiding Shapiro file the false returns? Does that mean Shapiro had planned to testify about other individuals involved in a bigger scheme, who were not part of this particular case, in exchange for avoiding tax-fraud charges against himself? Also, why were those convicted given such lenient sentences despite Shapiro’s planned testimony being the most likely motive for his high-profile murder?

The Mystery Deepens

Other questions are raised by Kessler’s history prior to the Shapiro slaying. Kessler had previously come under suspicion after the murder of his business partner Frank Yassenoff and Yassenoff’s fiancée Ella Rich in 1970, but Kessler was never charged with that crime. Yassenoff and Rich were found dead in Yassenoff’s car in his driveway. Two years later, Kessler was taken to court by the IRS for failing to provide records of an Ohio-based construction company, Brittany Builders, where Kessler was secretary and thus custodian of those records. Kessler was first ordered to provide the records, but the order was dismissed in 1973. One of the lawyers defending Kessler in both of these cases, Joseph F. Dillon of Detroit, Michigan, represented Detroit mafia figure Anthony Giacalone on federal tax-evasion charges in 1976. A decade later, Dillon was also involved as a lawyer for Arthur Shapiro’s estate in another case involving his fraudulent tax returns.

In 1972, the records of Brittany Builders were wanted in connection with a tax-liability investigation involving Carl and Sandra Neufeld; and the requested records covered the period from 1967 to 1969. Brittany Builders was incorporated in 1967 by Joseph L. Eisenberg, a Columbus-area lawyer and B’nai B’rith member, and was cancelled as a company in 1970, the year of Yassenoff’s death. Local media reports cite Yassenoff as having been president of Brittany Builders. Yassenoff’s son, Solly Yassenoff, later told the Columbus Dispatch that he knew for a fact that his father had been involved in bribing public officials in connection with real estate deals at the time he was president of Brittany Builders.

A year after the Brittany Builders case, Columbus police claimed that Yassenoff and Rich were killed during a robbery, a claim they had not made at the time of the victims’ deaths. The police also claimed that the prime suspect in the “robbery” and murders, Joseph Bogen, had been killed by his partner, Rudolph Glenn, by the time the claim that Bogen was the murderer was made. Police also stated that Bogen, Yassenoff, and Rich had all been killed with the same gun due to ballistics tests they had conducted, meaning that the gun Glenn had used to kill Bogen was also the weapon responsible for the deaths of Yassenoff and Rich. Yet, police also claimed that the gun in question was “never recovered,” even though they could have obtained it from Glenn. Glenn was cleared of any wrongdoing in Bogen’s death due to his claiming self-defense. The murders of Yassenoff and Rich are still classified as unsolved.

It later emerged that accountant Kessler was involved in resolving issues related to Yassenoff’s estate after his death, with Arthur Shapiro also being involved as the attorney for the executor of Yassenoff’s will. Kessler and a woman named Marjorie Dyer were the only witnesses who had signed Yassenoff’s will, and Kessler had come under suspicion when she died in a questionable automobile accident. It was later reported by the Columbus Dispatch that Kessler, Shapiro, and Yassenoff had all been “connected through a maze of business dealings.” Perhaps most unsettling of all was, when police investigators were looking for the files on the Yassenoff murder case during the investigation into Shapiro’s murder, they were unable to locate them, which suggests that some police official or officials had deliberately removed or destroyed those documents. The interconnectedness of Yassenoff, Shapiro, and Kessler and the aforementioned information suggests that law enforcement was involved in a series of cover-ups in Yassenoff’s, Rich’s and Shapiro’s murders and potentially in the death of Marjorie Dyer as well. Did Berry Kessler, an accountant, really wield enough influence in Ohio to avoid being heavily scrutinized for not just one but three murders? It seems unlikely.

No Ordinary Cover-Up

In the case of the Shapiro murder, more evidence that a cover-up had indeed taken place emerged in 1996, when the then Columbus police chief James Jackson was under investigation for corruption. As a part of that investigation, Jackson was charged with the “improper disposal of a public record for ordering the destruction of a report on the Shapiro homicide.” The homicide report had been written by Elizabeth A. Leupp, an analyst with Columbus police’s Organized Crime Bureau, and sent to the commander of the Intelligence Bureau, Curtis K. Marcum, on June 6, 1991. Jackson quickly suppressed the document and then ordered its destruction less than a month after it had been written. According to reports, Marcum bypassed protocol in carrying out Jackson’s order. The charge against Jackson was upheld by the Civil Service Commission, and he received a five-day work suspension for destroying a public record. Jackson had justified his actions by claiming that the report was “filled with wild speculation about prominent business leaders” and was “potentially libelous.”

Though the homicide report was believed to have been destroyed, it was obtained by Bob Fitrakis—attorney, journalist, and executive director of the Columbus Institute for Contemporary Journalism—in 1998 when Fitrakis was accidentally sent a copy of it as part of a public records request. When confronted with the document after Fitrakis reported on its contents, Jackson responded, “I thought I got rid of it,” adding that the report was “scandalous.” However, another high-ranking law enforcement official familiar with the Shapiro murder investigation told Fitrakis at the time that “the report is a viable and valuable document in an open murder investigation.”

The report is officially titled “Shapiro Homicide Investigation: Analysis and Hypothesis,” (hereafter in this article, the Shapiro Murder File). The report was most likely suppressed to protect Ohio’s two wealthiest men, who were both named in the document—Leslie Wexner and Edward DeBartolo Sr. Notably, the document does not once mention Berry L. Kessler. It does, however, mention John W. “Jack” Kessler, former Columbus City Council president and cofounder of the New Albany Company along with Leslie Wexner. It also mentions former Columbus City Council president Jerry Hammond and former Columbus City Council member Les Wright. Kessler later became a board member of Banc One and still later of JP Morgan and was involved in selecting Jamie Dimon as CEO of that bank.

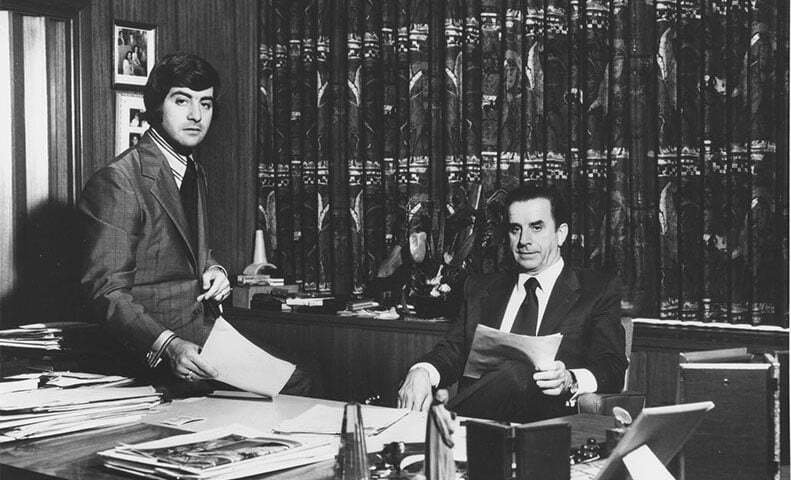

The document notes that the law firm where Shapiro worked, called Schwartz, Shapiro, Kelm & Warren at the time of his murder but later called Schwartz, Kelm, Warren & Rubenstein, was representing Wexner’s company The Limited. Arthur Shapiro, prior to and at the time of his death, managed The Limited’s account at the law firm and was in direct contact with Robert Morosky, the top man at The Limited after Wexner. Stanley Schwartz, a senior partner at Shapiro’s firm, took over The Limited account following Shapiro’s murder.

Shortly after Shapiro was killed, per the document, Schwartz incorporated Samax Trading Corporation, which was controlled by Wexner with the express purpose of engaging in “business liquidation.” Through Samax, the report notes, Wexner acquired 70 percent of Omni Oil/Omni Exploration and was elected to its board of directors along with Schwartz that same year.

However, Ohio state records show there is more to the story. Schwartz incorporated the Samax Trading Corporation and Samax Trading Company within one month of each other in 1987, per state records. Samax Trading Company did not adopt the name Samax until 1987 and had previously been called JAS Liquidation Inc. Company records include a consent letter stating that the board of directors of Lewex Inc., another company controlled by Wexner, had given its consent for JAS to adopt Samax as its trade name. Thus, it was JAS, not Samax, that was incorporated in 1985, but the company does not appear to have been incorporated in Ohio as it does not appear in that state’s records even though its address is listed as existing in Columbus, Ohio. It is possible that the company was reincorporated in Ohio under the name Samax two years after its initial creation, potentially to obfuscate its previous activities in liquidating “distressed businesses.” One month after JAS became the Samax Trading Company, the Samax Trading Corporation was also incorporated as an Ohio corporation by Stanley Schwartz as a holding company for shares in Omni Oil. Company records note that the trade name Samax Trading Corporation had been used by Schwartz and Wexner since July 1985.

The year that JAS became Samax, 1987, Schwartz also incorporated the Wexner Investment Company. Harold Levin, Wexner’s neighbor and top money manager from 1983 to 1990, was its initial president, according to the Shapiro Murder File. Levin was also listed as vice president of PFI Leasing, which shared the same telephone number and address as the Wexner Investment Company. PFI Leasing was incorporated by Levin in 1983, the year he began managing Wexner’s fortune. Records show the address of PFI Leasing as Schwartz, Kelm, Warren & Rubenstein (at the time listed as Schwartz, Shapiro, Kelm & Warren). The Shapiro Murder File also notes that, in 1986, Richard Rubenstein of Schwartz, Kelm, Warren & Rubenstein was given a speeding ticket while driving a vehicle registered to PFI Leasing Company.

The Wexner Investment Company, at the time the Shapiro Murder File was written in 1991, also shared an office with Omni Oil and Intercontinental Realty. Intercontinental Realty was incorporated the same year as the Wexner Investment Company with the involvement of Dorothy Snow, an attorney at Schwartz, Kelm, Warren & Rubenstein. The realty name, notably, is similar to the name of Epstein’s main company at the time—Intercontinental Assets Group.

At the time the Shapiro Murder File was written, the head of Wexner Investment Company and Wexner’s new money manager was Jeffrey Epstein, whose name is not mentioned in the Shapiro Murder File. Crucially, the year 1987, when many of these changes with Samax and the creation of the Investment Company took place, is the very year that Jeffrey Epstein officially began to serve as a financial adviser to Wexner. Levin was forced out of the Wexner Investment Company in 1990 after Epstein was put in charge, effectively demoting Levin and prompting him to resign a few months afterward. It is unknown how involved Epstein was in these different entities from 1987 until he formally became Wexner’s money manager in 1990. However, Epstein must have significantly benefitted Wexner in some major way during this period to warrant such a rapid and dramatic promotion within a three-year span.

Notably, once Epstein had taken over as Wexner’s top money manager, PFI Leasing was dissolved. Records of its dissolution list Wexner as director and president of PFI Leasing and Epstein as vice president. Levin had been delisted as the company’s agent just a few weeks earlier. Both Samax companies were similarly dissolved in 1992, though the records of their dissolution are not publicly available.

Around the time Epstein became involved with Wexner’s inner circle, in 1986, John W. Kessler and Wexner cofounded the New Albany Company. The Shapiro Murder File notes that the Wexner Investment Company and PFI Leasing shared a telephone number and office on the 37th floor of Columbus’s Huntington Center, which is also the address listed for John W. Kessler Company and the New Albany Company. A 1993 article in the Cleveland Plain Dealer and cited by Bob Fitrakis describes the origins of the New Albany Company as follows:

“Legend has it that in 1986 or so, Jack and Les were cruising in Les’ Land Rover near New Albany, about 12 miles from downtown Columbus. They saw acre after acre of empty farmland. Virgin soil. And thus the billionaire, getting a vision thing, declared to his buddy, this will be my new home.”

That same report states that “Wexner and Kessler formed the New Albany Co. and spun off a bunch of paper corporations to cover their footprints. Then their minions knocked on doors and made the proverbial offers you couldn’t refuse.” The business linkages between the New Albany Company, PFI Leasing, the Wexner Investment Company, the Samax companies, Omni Oil, and Intercontinental Realty are worth reconsidering given this context.

Per Fitrakis, New Albany’s success required changes be made to Columbus city policy and zoning laws. This is alluded to in the Shapiro Murder File as having been accomplished through questionable investments made by a Wexner-controlled entity in a jazz club run by former City Council member Jerry Hammond and his successor on the council, Les Wright. The Wexner-controlled entity in this case was called SNJC Holding Inc., incorporated in 1987, and gives the same address as the Wexner Investment Company at the Huntington Center. It then cites circumstantial evidence regarding how it was that Hammond was mysteriously able to make payments on a luxury apartment despite not having enough known income for such payments, suggesting a bribe had been paid. Hammond had also been “swept up in an emotional debate about the Wexley luxury housing project [i.e., the New Albany project] in 1988” and was accused by local officials of selling out the city’s interests to benefit his “friend” Leslie Wexner.

Even though the New Albany Company managed to secure this local policy change— however that was actually accomplished—other company projects were later accused of violating existing state and city laws, though no action was taken against the company.

Wexner and the Mob

The Shapiro Murder File also notes that a motive for Shapiro’s murder could be found in the IRS investigation, stating that Shapiro was due to appear before a grand jury in connection with that investigation the day after his murder. It states, “While the motive remains unclear, the suspect is an individual who (a) knew Shapiro and had some personal/professional contact with him; (b) would benefit from his death or from ensuring his silence; (c) had close contact with LCN [i.e., La Cosa Nostra: the Mafia, organized crime] figures or trusted LCN associates; and (d) had the personal financial resources to afford the cost of the contract (“hit”).”

The Shapiro Murder File strongly suggests that Wexner and/or his associates were involved in ordering and financing the “hit” on Shapiro. It discusses several transactions of questionable ethics and legality involving associates of Wexner, specifically Kessler, Wright, and Hammond, and some involving Wexner himself. Regarding these transactions, the report states, “Arthur Shapiro could have answered too many of these sort of questions, and might have been forced to answer them in his impending Grand Jury hearing; Stanley Schwartz might now be able to answer some of the same questions for the same reason, but does not face a Grand Jury, is immersed in the pattern [of questionable Wexner-linked/Wexner-adjacent transactions] himself, and now has a powerful incentive to maintain discretion.”

One important part of the Shapiro Murder File is related to the report’s discussion of Wexner associates with ties to organized crime, specifically the Pittsburgh Genovese-LaRocca crime family, which is associated with the National Crime Syndicate founded by Charles “Lucky” Luciano. Those named Wexner associates are Edward DeBartolo Sr. and Frank Walsh.

Edward DeBartolo Sr. was born in 1909 and got his start working for his stepfather’s construction business, Michael DeBartolo Construction. In the 1940s, DeBartolo founded his own company, Edward J. DeBartolo Corporation, and eventually became a real estate baron, particularly of suburban shopping malls and complexes. Some of his earlier ventures, such as the 1960 purchase of the Thistledown racetrack near Cleveland, Ohio, involved the Emprise Corporation, which was indicted and convicted in 1972 for racketeering and serving as a front for organized crime. In 1976, Cleveland Magazine described DeBartolo’s business empire as “deliberately labyrinthian” with each venture encapsulated as a separate corporation, some of them joint ventures with the real estate arm of a major retailer.

DeBartolo is described in the Shapiro Murder File as a Youngstown, Ohio–based real estate developer associated with Leslie Wexner. The report states that the two men “have a well-known history of business and investment partnerships, and in the late 1980s, twice attempted jointly to acquire Carter-Hawley-Hale Department Stores,” with that partnership having received considerable press attention at the time. The report goes on to state that DeBartolo is an “associate of the Genovese-LaRocca crime family in Pittsburgh,” information that—per other indications in the report—seems to have been sourced from the Pennsylvania Crime Commission. At the time of the Shapiro murder, the boss of the Genovese crime family in New York, which represented Pittsburgh on the Mafia Commission, was Tony Salerno, who was represented in legal matters by Roy Cohn.

There is much more to DeBartolo’s links to organized crime, however, than those mentioned in the Shapiro Murder File. According to investigative journalist Dan Moldea, a 1981 report from US Customs Service special agent William F. Burda asserted that DeBartolo’s business empire was “operating money-laundering schemes, realising huge profits from narcotics, guns, skimming operations, and other organized crime–related activities” through Florida-based banks in which DeBartolo had controlling interests.” Burda further stated that DeBartolo’s organization, specifically those parts of his empire based in Florida, had reported “ties to [Carlos] Marcello, [Santos] Trafficante, and [Meyer] Lansky and, because of its enormous wealth and power has high-ranking political influence and affiliations.”

An earlier report authored by Burda and cited by Moldea stated that “Meyer Lansky, the financial wizard of OC [Organized Crime], is now considered by most to be almost senile and getting out of the business. His successor and new financial wizard is recognized as Edward J. DeBartolo.”

The ties of DeBartolo to criminal activity as mentioned in Burda’s reports are supported by other documents. For instance, a confidential report from the Florida Department of Law Enforcement stated that the “WFC Corporation is a cover for the largest narcotics operation in the world” and further states that the organization, under federal and Florida state investigation in the late 1970s, had been heavily influenced by Santos Trafficante. In 1979, Florida authorities were investigating “spurious loans made by WFC Corporation from its Grand Cayman Island subsidiary, through Metropolitan Bank and Trust Company of Tampa, a banking institution whose majority stockholder is Edward DeBartolo Sr.” DeBartolo had bought Metropolitan Bank in 1975 and held such a strong position that he was able to unilaterally force the resignation of the bank’s president in 1981, with other board members having no say in the matter whatsoever. The bank collapsed a year later, which bank leadership attributed to bad real estate loans. At the time, it was the largest bank failure in Florida history.

Furthermore, DeBartolo appeared on the Justice Department’s 1970 Organized Crime Principal Subjects List, which listed individuals with suspected links to organized crime. In the late 1970s, a FBI wiretap of Los Angeles-based mob figure Jimmy Fratianno picked up Fratianno’s discussions about DeBartolo being “very friendly” with Ronald Carabbia, the mob boss of DeBartolo’s hometown of Youngstown, Ohio.

Wexner’s cozy association with DeBartolo is thus highly significant. While the Shapiro Murder File reports there is a connection between DeBartolo and organized crime, it offers little in the way of specifics, whereas other sources, including Dan Moldea, further elucidate this connection. Indeed, this additional information shows that DeBartolo worked with known mob figures throughout the country and was close to several high-ranking members of the National Crime Syndicate, in addition to allegations that he had taken on the mantle of Meyer Lansky himself. As discussed in my original series on the Epstein case for MintPress News, Meyer Lansky was a key figure in the organized crime–intelligence alliance that later gave rise to Epstein and his sex-blackmail activities.

DeBartolo was one of Ohio’s richest men during his lifetime and, like Wexner, lived his life above the law, having investigations and charges dismissed left and right due to his power and political influence. That legacy has continued with DeBartolo’s son and heir, Edward J. DeBartolo Jr., who was pardoned by Donald Trump for gambling fraud right before the president left office.

Another close business partner of Wexner’s mentioned in the Shapiro Murder File, Francis J. “Frank” Walsh, similarly had ties to organized crime, specifically the “Genovese crime family.” As the Shapiro Murder File notes, Walsh was “owner and chief executive officer of Walsh Trucking Company out of New Jersey” and “Walsh Trucking is/was the major transporter for The Limited” in Columbus. The document goes on to note that Walsh was under investigation by the New York Organized Crime Task Force in 1984, and all notices sent to Walsh in connection with this investigation were addressed to Frank Walsh Financial Resources at One Limited Parkway, Columbus, Ohio—the same address as Wexner’s The Limited.

In addition to what is mentioned in the Shapiro Murder File, Frank Walsh was charged in 1988 by then US Attorney Samuel Alito Jr., now a US Supreme Court judge, with paying thousands to officers of a corrupt Teamsters union as was well as members of the Genovese crime family in exchange for a sweetheart union contract. This supports the claim in the Shapiro Murder File, though that document does not mention this incident, that Walsh had ties to the Genovese crime family. Per Alito, the case “illustrated how certain seemingly legitimate businesses are able to get a jump on their competitors by entering into an agreement with organized crime and it illustrates how organized crime is able to get enormous profits by entering into an agreement with seemingly legitimate businesses.” Tony Salerno, the Genovese crime boss, was listed as an unindicted co-conspirator in the case.

After the charges were filed, Walsh was arrested at his home. According to his lawyer, Walsh by then had somehow become a real estate developer worth between $60 and $100 million, while Walsh Trucking, among other companies of his, had been forced into bankruptcy by an antitrust suit. Walsh pled guilty to the charges and was sentenced to four years in prison in 1990.

Similar charges surrounding Walsh and a corrupt Teamsters union local surfaced years later, in 2003, when the Teamsters union filed internal charges against a member of their executive board, Donato DeSanti, for “helping Walsh, whom he knew to be a convicted labor racketeer with ties to organized crime, manipulate officers of [Local]107 into cooperating with a scheme DeSanti knew or should have known was of questionable legality.” The union further charged DeSanti with hiding Walsh’s past conviction and organized crime association from union members.

Whitewashing Wexner

While Berry L. Kessler may well have had a role in Arthur Shapiro’s death, it seems unlikely that he had the political pull to get police to cover up several, apparently connected, murders—those of Arthur Shapiro, Frank Yassenoff, Ella Rich, and potentially Marjorie Dyer—or the financial resources to pay for a professional contract killing. Given the evidence, it appears that Kessler was a deeply corrupt operator, but most likely only a middleman for the dirty deed if he was involved in the “hit” on Shapiro.

Concerns about the deeper forces at work in these cases appear to be what led Columbus police investigators to produce a document like the Shapiro Murder File in the first place, and its suppression and attempted destruction suggest that the scrutiny was aimed squarely at Leslie Wexner, which was too close for comfort for those in Ohio law enforcement who sought to protect the criminal nexus ultimately responsible for Shapiro’s death. Wexner’s involvement with suspect entities and actors came to light well after the Shapiro case, but the blatant murder of The Limited’s lawyer is the first documented instance of this connection and, arguably, one of the most important.

Wexner and many other wealthy “clients” of Jeffrey Epstein have taken great pains to develop sophisticated PR strategies aimed at keeping their reputations unscathed from the continuing fallout in the Epstein case. Wexner and others, such as Bill Gates, have pursued a narrative where all bad deeds are attributed to the now conveniently dead Jeffrey Epstein, while his enablers, accomplices, and close associate were merely duped by Epstein’s charisma or manipulated by his wiles. Many of these individuals, however, and particularly Leslie Wexner, clearly have something to hide.