When Robert Maxwell’s body plunged into the cold waters of the Atlantic on November 5th, 1991, he left in his wake a seemingly endless parade of unanswered questions about the many lives he had led. In his outward facing persona, he was a giant in the world of media, controlling everything from major publishing houses to newspapers. Towards the end, this facade had crumbled under the weight of revelations that he had systematically looted the pension funds of his employees. This points towards Maxwell’s other life: that of a serial criminal, whose crimes escalated from theft to involvement with a worldwide network of organized crime outfits— with the Russian mafia, the Japanese Yakuza, and Chinese Triads just being some key examples.

There was the life of Robert Maxwell the arms merchant, thanks to the globe-trotting activities of his close business partner, Nick Davies. This life was overshadowed by that of Robert Maxwell the spy, with an espionage career stretching back to jaunts with British intelligence during the Second World War. Work for MI6 seems to have been long-running for Maxwell, but he tirelessly collected fellow—and rival—intelligence agency contacts throughout the years. The most important of these was his connections to the Israeli intelligence apparatus, though he also nurtured ties to American intelligence, and to the Soviet KGB.

This impressive range of contacts saw Maxwell embroiled in the infamous PROMIS affair, a joint CIA-Mossad operation that involved a case management database software, developed by Bill Hamilton and his company Inslaw, which had been stolen by a joint effort involving Israeli spymaster Rafi Eitan and President Ronald Reagan’s Justice Department. One of the versions of PROMIS that was fitted with a “trap door” was weaponized by Systematics, a bank data processing firm owned by Arkansas financier Jackson Stephens, and by figures operating at a weapons development facility located on the Cabazon Indian Reservation in Indio, California. This trap door allowed intelligence agencies to peer into users of PROMIS, and so the software was sold to enemy and ally alike. Maxwell was selected as one of the ‘salesmen’ to peddle PROMIS abroad.

The entire operation advanced along several parallel tracks. Maxwell, working for the Israelis, marketed PROMIS to intelligence agencies and national security installations around the world and within the US, including to Los Alamos and Sandia laboratories. The version of PROMIS marketed by Systematics, meanwhile, was sold to large banking institutions, particularly those in Switzerland. This appears have to be been part of the CIA’s “follow the money” program, which tracked and monitored the financial flows of rival nations.

Against this backdrop there are lesser known, but by no means unimportant, activities that Maxwell engaged in. One of these was his attempted purchase in 1988 of a Texas savings and loan (S&L) institution that became known as Bluebonnet. Since his involvement with the company was brief, sputtering out at about four months of negotiations, it would be tempting to write it off as a footnote in the broader Maxwell story—except for the fact that effectively every person involved in the story of Bluebonnet and its sale was connected, in one way or another, to serious financial crime, arms dealing, and the theft and distribution of the PROMIS software.

Understanding Bluebonnet requires unpacking a tangled and diffuse web of fraudsters, intelligence assets, bankers and real estate developers who together rampaged across Texas and surrounding states during the mid-1980s, bilking and crashing a near-limitless number of thrifts and related lending institutions in a then-unprecedented spree of brazen financial crime. Much of this was exactly what the mainstream narrative of the S&L crisis said it was: runaway greed enabled by deregulatory fever, which allowed crooks to spirit away untold sums. Yet, this isn’t the full picture. In many instances, it seems that money was siphoned off into offshore accounts, where it was then used to help finance covert intelligence operations—support for the Contras of Nicaragua, and for the transfer of arms and sensitive technology to the Middle East.

It also requires understanding Maxwell’s unique relationship to Texas. The state and its long history of political corruption rumbles quietly below the story of Maxwell and many of his most notorious affiliates. Take Jeffrey Epstein, for example. His involvement with the Maxwells likely began with his introduction into the world of arms dealing, forged in large part by his alliance with British arms dealer Douglas Leese. According to Leese’s son, Julian Leese, Epstein reportedly first connected with Leese after meeting him at a party that was hosted by a person described as “a well-known oil baron down in Texas.” Per this account, Epstein had first met Leese’s other son, Nicholas, who then brokered the subsequent introduction between Epstein and his father.

The identity of this “oil baron” remains unknown, but ties made in Texas proved enduring for Epstein. In 1982, Epstein placed—and subsequently stole—hundreds of thousands of dollars from Chicago businessman Michael Stroll, which had been for the ostensible purpose of investing in Texas oil producers. As for his Texas-born relationship with Douglas Leese, arms trafficking wasn’t the only door opened for Epstein. Leese reportedly introduced Epstein to Steven Hoffenberg, who then brought him to work for his company, Towers Financial. In 1993, Towers Financial was unveiled as the operator of a massive Ponzi scheme—though the late Hoffenberg has more recently alleged that Epstein was using the company to wash profits from the lucrative arms trade.

Mark Thatcher, son of British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, was another associate of Robert Maxwell who arrived in Texas in this same period. He began visiting the state in 1983, and relocated his operations there three years later. Former Israeli intelligence officer Ari Ben-Menashe has charged that during his time in Texas, Thatcher was involved in the clandestine shipment of arms to Iraq—an allegation that spawned a spirited debate in the halls of British Parliament. Perhaps more importantly, Thatcher did have dealings with arms dealer Ian Smalley (also known by the pseudonym “Doctor Doom”), a known provider of weapon systems to both Iran and Iraq. Smalley, at the time, lived on a cattle ranch not far from Dallas, Texas.

Thatcher enjoyed the protection of powerful Texan political figures during his time in the Lone Star state. In 1986, he was facing eviction from his Dallas condominium due to “security requirements” put in place because of his fear of “terrorism.” The eviction was continuing apace until former Senator John Tower intervened, and apparently arranged for Thatcher to receive Federal protection.

It was notably John Tower himself who was Maxwell’s most important Texas contact. Tower had been brought to Maxwell’s attention by none other than Henry Kissinger, who had suggested that the former senator would be the person most suited to open doors necessary for Maxwell’s sale of PROMIS to specific state-run facilities in the United States. Kissinger reportedly made this suggestion to Maxwell sometime in early 1984, while Tower was still in office and serving as head of the Senate Armed Service Committee. Tower would act as Maxwell’s agent until 1986 when, having left office, he joined the board of Pergamon, Maxwell’s scientific publishing press. Throughout the period of his involvement with Maxwell, Tower was reportedly on Mossad’s payroll.

Tower’s impressive roster of contacts connected Maxwell to the commanding heights of the Reagan administration and the prevailing conservative establishment. He also placed the media mogul and spook into the direct proximity of a powerful network in Texas, one with deep complicity in both savings and loans fraud and shadowy covert operations.

Savings and Loans and “Off-the-shelf Operations”

John Tower’s political career long enjoyed the backing of one of Texas’ great political king-makers: construction magnate, land developer and banker Walter Mischer. Though it’s not exactly clear how Tower and Mischer first connected, Mischer headed up the Democrats for Tower, a Democratic Party outreach arm of Texans for Tower, in 1978. Mischer and Tower also moved in the same social circles. For example, mutual associates of each included Robert F. Stewart III, a prominent Texas businessman, and Eddie Chiles, the owner of a large petroleum industry services concern.

Besides Tower himself, Mischer had his own ties to the business circles around Robert Maxwell. One partner of Mischer’s in a major land development project in west Texas was a man named Robert O. Anderson, the figure behind the powerful Atlantic Richfield oil company. Anderson, in turn, was a frequent business partner of Tiny Rowland, a British businessman who counted Maxwell among his circle of closest friends (there are rumors that Rowland helped broker the sale of PROMIS to African countries where his company, Lonrho, had considerable sway). Among the ventures where Anderson and Rowland could be found together was at the British media company The Observer. In 1984, Rowland initiated talks with Maxwell to sell The Observer, though their negotiations bore little fruit.

Mischer’s flagship corporation was Allied Bank, a consolidated banking combine that had been set up in the 1970s and subsequently grew to be Houston’s fourth largest bank by the 1980s. It is through Allied that one can see a fuller picture of Mischer’s ties to the S&L crisis: one of the bank’s prominent customers was Herman K. Beebe, a Louisiana-bred businessman and mob insider who controlled a sprawling empire of banks, insurance companies, nursing homes, and hotel franchises through his Shreveport-based AMI, Inc. AMI borrowed heavily from Allied, and Beebe guaranteed loans from the bank to various fraud-ridden thrifts.

Since around 1976, Beebe became closely linked to former Texas lieutenant governor (and notorious S&L looter) Ben Barnes—himself an intimate crony of Walter Mischer. Despite the 1987 collapse of the multi-million dollar real estate empire that he controlled in partnership with former Texas governor John Connally, Barnes was listed as a director of Steven Hoffenberg’s Towers Financial in 1990, the same period that Epstein was affiliated with the company. Hoffenberg must have been impressed with Barnes’ financial track record, as the former politician was placed on his company’s audit committee.

Recent reporting by the New York Times illustrates how close Barnes himself was to intelligence circles. According to Barnes, in 1980, he participated in a “mission to the Middle East” spearheaded by Connally, the purpose of which was to “sabotage the re-election campaign” of President Jimmy Carter. The pair’s Middle Eastern tour entail meetings with various leaders, where Connally delivered a message intended to be passed to Iran, advising them not to release hostages prior to the election. A report on this trip was then provided to Reagan’s campaign manager and future CIA director William Casey.

Barnes also states, conveniently, that he was unaware of the intention of his trip when he agreed to accompany Connally. At any rate, Barnes’ story is just one example of several overlaps between the “October Surprise” plot against Jimmy Carter and the subsequent S&L crisis. William Casey’s alleged pilot during his meeting with Iranian representatives in Paris was Heinrich “Harry” Rupp, who was also involved in S&L-linked bank fraud in the mid-1980s (details of this fraud will be discussed in part 2 of this article). These sorts of murky ties to the underworld of covert operations also orbit a close associate of Barnes and Connally, Herman Beebe.

A 1985 Comptroller of the Currency report details well over a hundred banks and S&Ls where Beebe exerted hidden control. The report states that Beebe’s “influence and control flows through an extensive web of corporate enterprises and nominees.” Through this vast machine, Beebe became the ultimate wheeler-and-dealer, participating in the looting of countless S&Ls in a manner that confounded law enforcement and federal regulators alike. As journalists Stephen Pizzo and Mary Fricker recount, Beebe “could shift fraudulent deals not only from institution to institution and district to district but from regulatory system to regulatory system—which would make him almost impossible to stop.”

The 1985 Comptroller of the Currency report names Palmer National Bank of Washington, D.C. as one of the banks where Beebe held sway (he had, in fact, helped provide start-up capital for the institution). Palmer’s first chairman was Stefan Halper, the son-in-law of longtime CIA official—and ardent Cold Warrior—Ray S. Cline. During the course of the investigation into the Iran-Contra scandal, Palmer was revealed to have been utilized as a mechanism for moving covert funds destined for the Contras in Nicaragua.

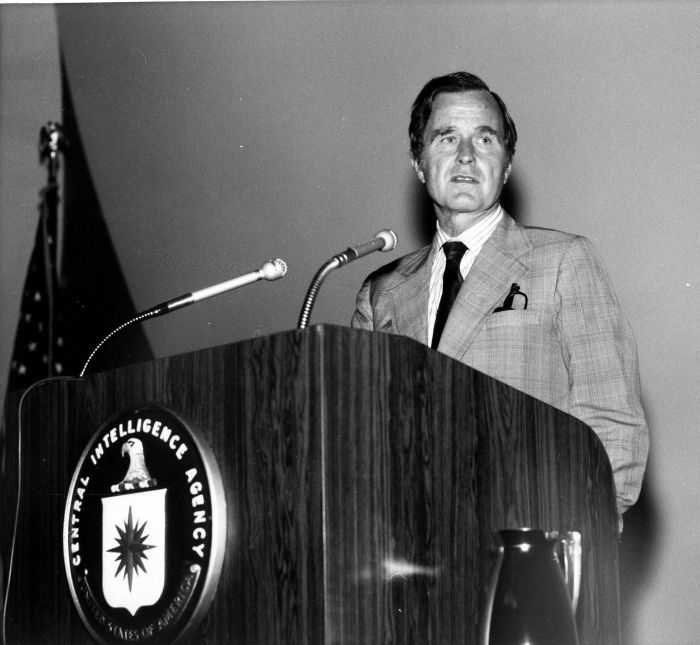

Like his friend Beebe, the aforementioned Walter Mischer was also plugged into the intelligence apparatus, though the full details of his activities in that context remain obscure. Former Houston Post reporter Pete Brewton, in his book The Mafia, the CIA, and George Bush, recounts how multiple law enforcement and political sources informed him that Mischer had been recruited into something of a private intelligence apparatus that was organized by George H.W. Bush after Jimmy Carter became president and began his controversial reforms of the CIA. By the 1980s, under Reagan’s CIA director William Casey, it seems that Mischer continued to work within the orbit of the Agency.

According to Brewton’s sources, Mischer and Bush decided to use Mischer’s former son-in-law, Robert Corson, as a “cut-out” for their intelligence activities. Corson became known to law enforcement as a money launderer who was active in moving money around domestic banks and savings and loans and even ferrying money in and out of the country. The CIA might not have been the only intelligence service that Corson dealt with. “A Texas law enforcement official”, writes Brewton, “…confirmed Corson’s work for the CIA. This officer said that Corson also did work for the Israelis, but may not have known it because there were several layers of cutouts between Corson and the Israelis.”

Could this Israeli connection have come through Mischer’s friendship with Maxwell’s agent, John Tower? It is likely that this question will never be answered. However, it is interesting to note that one business associate of Mischer and Corson, Joe Russo, ended up partnered with Earl Brian – an architect of the PROMIS theft – in the late 1980s in the ownership of the media outlet UPI.

Additional information about Corson can be found in the surviving papers of Danny Casolaro, particularly in the documents provided to him by former undercover Customs investigator Robert Bickel. One document found in these papers is an investigative summary written by Rebecca Sims, a former employee of Corson’s who became a freelance sleuth investigating covert CIA financial activity as well as an expert in S&L fraud. There, Sims recounts that CIA-linked arms dealer and controversial Iran-Contra whistle-blower Richard Brenneke informed her that “Corson had been involved with Norman Callahan… and Allsource Air concerning gun shipments to Iran.”

Sims eventually determined that “Allsource Air” was in fact Air Source Express, an aviation company headquartered in Bridgeton, Missouri, with offices in Houston. Missouri Secretary of State records show that the proprietor of Air Source was Richard Baum, who had established the company in April 1982. Baum’s wife, Judy Baum, ran the company’s subsidiary, Plan Freight, Inc. In 1987, she became an administrator for the American Society for Technion—with Technion being Israel’s technology-oriented public research university.

Other documents provided by Bickel to Casolaro identify Norman Callahan as an “associate” of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and supervisor for “the Demavand project from its inception.” While it is not well known, Demavand was the code name for a large-scale, clandestine flow of weapons to Iran that took place prior to the arm sales of the Iran-Contra affair. Among those implicated in this shadowy operation was “Mr. Boyle”, the code-name for a National Security Agent officer; French arms dealers John Delaroque and Claude Lang; and Michael Austin, the owner of a Manhattan-based defense firm called Austin Aerospace.

The New York Times reported that Austin Aerospace’s board of directors included Major General John K. Singlaub, a long-standing intelligence operative who was also implicated as a participant in the Iran-Contra affair. At the time that Demavand was up and running, Singlaub was a principal in an arms trafficking outfit called GeoMiliTech (GMT). GMT, which had offices in the US and in Israel, was revealed to have brokered arms transactions with Nicholas Davies, the foreign editor of Maxwell’s Daily Mirror. Like his boss, Davies was an active Israel intelligence asset at that time.

“Demavand” does not appear anywhere in the thousands of pages of Iran-Contra testimony. Norman Callahan appears one time, in the deposition of former high-ranking CIA officer Ted Shackley. When asked if he knew a “Norm Callahan”, Shackley responded that he “didn’t recognize Norman Callahan.” There was more to his answer, however, but the details still remain redacted from the public record.

Richard Brenneke denied that this particular deal involving Corson was part of Demavand, but other documents provided to Casolaro by Bickel show that Sims believed Brenneke was lying, and that the deal was indeed part of this covert operation. Whatever the answer to this mystery may be, what is certain is that, within a few years of this deal, Corson launched himself into notoriety through his involvement in a series of massive, complicated savings and loan frauds that bear the classic hallmarks of money laundering.

Among the dubious S&L ventures that Corson found himself embroiled in was a 1985 joint venture with Bellamah, a large home building company based in New Mexico. The details of the venture are immediately suspicious: Bellamah and Corson purchased nearly three-hundred acres of land in Houston marked for development, but as Brewton points out, “Bellamah put up the entire $4.4 million purchase price.” An additional $11 million in loans were added onto the project courtesy of the easy-lending of Houston’s MBank, a bank with long-standing ties to Corson. In the end, Bellamah bought out Corson’s “stake” in the venture—netting Corson $33,000 despite the fact that he had never put money into the project—and subsequently defaulted on the MBank loan.

In the aforementioned investigative summary drafted by Rebecca Sims, it is alleged that Corson and Bellamah were involved with another entity called Meadows Resources. A source, Sims reported, told her that Meadows “was a company used to fund money for covert, off-the-shelf operations.” While this cannot be confirmed, Bellamah did indeed have a long-running partnership with Meadows Resources, an investment and land development subsidiary of the Public Service Company of New Mexico.

Importantly, Bellamah had previously been owned by the Gouletas family, a high-wheeling crew of condominium syndicators and land developers out of Chicago. The Gouletas had, on paper, owned Bellamah from 1977 through 1982, when it was sold to a group that included Douglas Crocker II—a high-ranking officer in American Invesco, the Gouletas’ primary corporate umbrella. This raises the question of whether or not the Gouletas had actually disposed of their holdings in Bellamah, or had merely shuffled the holdings around in an effort to raise capital for their other ventures.

As discussed in the second volume of One Nation Under Blackmail, the Gouletas family had significant ties to both Jeffrey Epstein and to figures involved in the PROMIS scandal. Evangeline Gouletas-Carey, part owner of American Invesco and wife of former New York governor Hugh Carey, shared office space with Epstein in the Villard Houses, a historic building located in New York City’s Midtown Manhattan neighborhood. While little is known about the exact nature of the joint endeavors that the Gouletas and Epstein engaged in, it is worth noting that Epstein for a time was presented in the media as a real estate developer, and a paper trail does exist showing his involvement in the buying and selling of several New York City properties—including some marked for condominium development.

It would be none other than Steven Hoffenberg of Towers Financial who claimed to have set Epstein up in the Villard Houses offices, which suggests that there might have been some sort of coordination happening between the respective financial frauds of the Gouletas and Towers Financial. The mutual connections of each to the same intelligence-linked circles in Texas warrants further scrutiny.

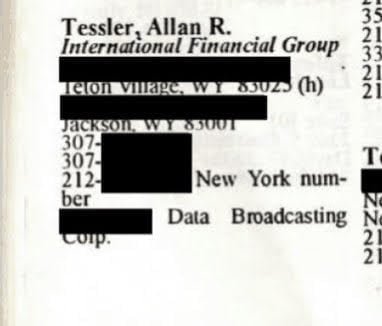

At this same time, the Gouletas had retained the legal services of Allen Tessler, an attorney from the powerful law firm of Shea & Gould. Among Tessler’s duties for the Gouletas was managing Imperial Savings, a thrift in California that the Gouletas had purchased from Saul Steinberg. Yet, the Gouletas were far from Tessler’s only notable client—he was also the close friend of and attorney for Earl Brian, and had served on the board of numerous Brian-controlled companies. Tessler appears in one of Epstein’s leaked contact books, with a number listed for Data Broadcasting Corp.—one of Brian’s companies.

SEC filings show that Tessler also spent a decade, from 1977 through 1987, on the board of The Limited, the clothing company owned by Epstein’s close associate Leslie Wexner. During this time, he served as a member of The Limited’s finance committee, and was one of two members of the board’s Nominating Committee (which selects nominees for board membership). The other member was Wexner himself.

A year after he entered into the ill-fated partnership with Bellamah, Robert Corson called upon the resources of MBank to take control of Kleberg County Savings Association, a small thrift in Kingsville, Texas. Corson promptly rechristened Kleberg as Vision Banc, and proceeded to loot the savings and loan dry, driving it into bankruptcy within two years. Inflicting a particularly grievous injury to Vision Banc’s finances was its involvement in a sweeping, multi-state $200 million land fraud in Florida, which led to millions being siphoned away into a network of offshore banks on the Isle of Jersey. The ties of these same banks to the Maxwells will be discussed in the final section of this article.

The ringleader of this elaborate scam was Mike Adkinson, a Texas land developer and rumored arms dealer who was suspected of working for the CIA (when asked under deposition whether or not he worked for the Agency, Adkinson responded that he “was not at liberty to disclose that information”). Also implicated was Lawrence Freeman, a Florida attorney who had previously been the law partner of Paul Helliwell, a veteran of American intelligence services whose infamous Castle Bank & Trust, located in the Bahamas, had moved money for both the mob and the CIA. When it came to the looting of America’s savings and loans, it seems that presence of operators from the clandestine world of intelligence was a pattern that reoccurred with alarming consistency.

Bluebonnet, Round 1: The Maxwell Bid

Thanks in no small part to operators like Robert Corson, Mike Adkinson and Herman Beebe, the late 1980s was marked by a domino-effect of S&L failures. Hotspots for this slow-moving financial crisis included California, Illinois, Arizona, and, perhaps most notably, Texas. In order to try and stem the steady stream of collapses, the Federal Home Loan Bank Board and the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation set in motion various emergency schemes. More often than not, this entailed rolling shattered thrifts into consolidated packages and selling them off to stable financial institutions. Frequently, the ultimate beneficiaries of these deals were large Wall Street banks and investment houses, allowing them even greater control over the nation’s lending industry.

One such emergency response was the Southwest Plan. With billions in Federal funding, the Southwest Plan consolidated a number of thrifts across Texas and surrounding states. Bluebonnet (originally labeled “Rose/Pard”) was the name given to one particular consolidation involving fifteen thrifts that was carried out in 1988 under the Southwest Plan. At least two of the S&Ls bundled into Bluebonnet, Sentry Savings of Slaton and Hi-Plains of Hereford, can be found in hand-drawn diagrams made by Arthur Leiser, then the senior examiner for the Texas Savings and Loans Department. Leiser’s diagrams detail the inner-workings of a sprawling “daisy chain” of bad loan-making and money laundering through countless thrift institutions, as well as interlocking webs of ownership structures.

It was Leiser who pursued Herman Beebe as far as he could go, tracking his presence all across this particular “daisy chain.” Beebe and his company, AMI, can be found in various diagrams, as can Mischer’s Allied Bank. Leiser showed that one of the Bluebonnet S&Ls, Sentry Savings, was doing business with Texas banker Sam Spikes, who appears in the 1985 Comptroller report as a figure involved in Beebe’s network.

When Bluebonnet was placed on the market, the first prospective buyer was Weston Edwards. Up until just a few months prior to his bid for Bluebonnet, Edwards was the senior executive vice president of Houston’s large mortgage lender, Lomas & Nettleton, which was controlled by the prominent Democratic Party fundraiser Jess Hay. Pete Brewton notes that “Lomas & Nettleton was very close to MBank”—the Texas bank that worked frequently with Robert Corson—with the two institutions sharing several directors. He adds that another customer of Lomas & Nettleton was the international arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi, a key player in Iran-Contra whose personal contacts included Jeffrey Epstein and Robert Maxwell.

The close proximity of Lomas and MBank are further confirmed by their mutual participation in a revolving line of credit to the General Homes Corporation, a Houston-based real estate company that frequently did business with Corson. Between 1978 and 1982, General Homes was controlled by Cadillac Fairview, a real estate investment vehicle owned by the Bronfman family. Control passed from the Bronfmans to the American Savings and Loan Association of Florida, where one could find Marvin Warner, the corrupt financier and Democratic Party insider involved in the high-profile collapse of Home State S&L of Ohio. Warner was a banking partner of Bruce Rappaport, a close friend of CIA director William Casey and himself no stranger to financial fraud and intelligence operations alike.

American Savings participated in the credit lines to General Homes alongside Lomas and MBank, as did Valley National Bank of Phoenix, Arizona. Former Mossad operative Ari Ben-Menashe has alleged that accounts at Valley National were utilized by Earl Brian and by Carlos Cardoen, a Chilean arms dealer who sold weapons—and the PROMIS software—to Iraq. As Whitney Webb noted in a recent Unlimited Hangout report, both Valley National and MCorp (the parent company for MBank) were both subsequently acquired by Ohio-based Banc One. This bank, which was extremely close to the circles around Leslie Wexner, was identified as a conduit for washing money connected to covert arms deals.

Documents made public during an examination of the efforts to sell Bluebonnet show that Weston Edwards was in active communication with Jess Hay, who agreed to make Lomas a partner in the acquisition. Lomas also agreed to provide $5 million in financing to Edwards. Curiously, Hay wrote to Edwards that they had learned that “this transaction, if it is consummated, is likely to close in October [1988] or expire if it is not accomplished by Election Day”—a reference to the upcoming electoral battle between George H.W. Bush and Michael Dukakis. This will not be the last time that Bush appears in the Bluebonnet story.

At the time that Hay committed the resources of Lomas to Bluebonnet, Edwards had already found his primary backer: Robert Maxwell. The entry point of Maxwell into the plan had come through John Tower. The congressional examination of Bluebonnet described Edwards’ “affiliation and association with former Senator John Tower”, and noted that Tower was “very much a presence” in the ongoing negotiations. Perhaps importantly, these deals were taking place more or less simultaneously with Tower’s failed bid to take over Texas’ First Republic Bank, which at the time was contemplating a purchase of MCorp—the holding company for MBank.

Given that Tower was attempting to gain control of Bluebonnet for Maxwell, in league with the former executive vice president of MBank’s affiliate, Lomas & Nettleton, it is worth asking if the attempted acquisition of First Republic was some sort of related maneuver.

These moves took place alongside a broader effort by Maxwell to extend his financial empire. In the same month that he began striving to take control of Bluebonnet, he launched his takeover of publishing house Macmillan, Inc. (guiding Maxwell’s hand in this endeavor was Robert Pirie, representing Rothschild family interests that had been “yearn[ing] for a prominent foothold in Wall Street”). 1988 was also the year that Maxwell truly began to consolidate—and systematically loot—a number of pension funds, allowing him to rapidly expand his economic war chest.

Maxwell’s expansionary phase, combined with his increasing interest in American business, took place as his involvement in the shadowy underworld of intelligence and organized crime deepened. Author Gordon Thomas alleges that, in 1988, Maxwell helped introduce Semion Mogilevich, the notorious and powerful Ukranian-Russian mafiosi, to the “western financial world”, and reportedly aided him in securing an Israeli passport. Within a year, Mogilevich was living in Israel and was able to use his Israeli passport to penetrate the financial networks of Israel and many other countries, including the United States.

In the course of the congressional inquiry into Bluebonnet, it was stated that Maxwell had backed out of the acquisition bid on November 7th, 1988. The timing was auspicious. Three days prior, on November 4th, Macmillan’s board of directors committed themselves to Maxwell’s takeover of the publishing giant, determining that Maxwell’s bid was “in the best interest of all shareholders.” Simultaneously, a competing interest in the takeover, a group led by billionaire Robert M. Bass, agreed to sell their shares to Maxwell.

By coincidence or not, Bass—an inheritor of one of Texas’ storied oil fortunes—had his own ties to the world of savings and loans. Concurrent with his attempt for control of Macmillan, Bass began to pursue the purchase of American Savings & Loan of California (not to be confused with the American Savings & Loan Association of Florida, which was mentioned above). A deal was consummated with the Federal Home Loan Bank Board in December 1988, a month after Bass sold his Macmillan shares to Maxwell. In acquiring American Savings, Bass committed an initial payment of $350 million—and the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance made available nearly $2 billion in subsidies to ensure the transaction.

There was also Richard Rainwater, a longtime financial advisor and strategist for the Bass family. A powerful figure in Texas business in his own right, Rainwater’s associates included George Aubin, a fixture in the S&L raider circles around Robert Corson and a known business partner of Herman Beebe. By the time that Bass was chasing Macmillan and American Savings, Rainwater had struck out on his own, dipping his toes into a mad-cap chase for beleaguered Texas financial institutions. He also appeared to have been acting as something of an unofficial financial manager for his close friend, George W. Bush.

As for Weston Edwards, efforts to acquire Bluebonnet continued despite Maxwell’s departure. His first post-Maxwell backer was the Lodestar Group, a boutique Wall Street investment firm founded by Merrill Lynch’s Ken Miller. Although Lodestar’s commitment was only brief, it soon ended up with another entity within this particular network. In 1989, Miller’s company purchased the daycare operator Kinder-Care. During the 1970s, Kinder-Care had been owned by the aforementioned Marvin Warner, whose American Savings in Florida had purchased the Bronfman’s stake in the company that did considerable business with Corson, General Homes. It’s telling, then, that during the late 1970s, Corson built daycares—using loans from Mischer’s Allied Bank—which he leased to Kinder-Care.

At the time that Lodestar was buying Kinder-Care, the daycare company owned a controlling chunk of American Saving of Florida, where Warner had held sway (he had departed the company, however, by the time of Kinder-Care’s acquisition). This was the same American Savings that partnered with Lomas & Nettleton, MBank, and Valley National Bank to provide a revolving line of credit to General Homes.

After Lodestar’s brief appearance, a third party appeared in the orbit of Bluebonnet. A letter from Edwards to Angelo Vigna of the Federal Home Loan Bank of New York, dated December 5th, 1988, contrasts the “Bob Maxwell proposal” to a more favorable proposal offered by the Deerpath Group, a merchant bank operating from a suburb of Illinois. Deerpath, in turn, had enticed a variety of partner companies, including real estate and utility concerns from Indiana and a shopping mall builder from Mississippi.

And with that, Edwards was out. On December 7th, two days after submitting the Deerpath proposal, Edwards was informed that he was no longer in the running for Bluebonnet. The Feds instead opted to offload the consolidated thrift onto an insurance businessman name James Fail—but the acquisition rapidly blossomed into something of a scandal. Widely circulated accusations charged that Fail had obtained Bluebonnet due to political cronyism and ties to the heights of political power in the United States. It was also alleged that pressure coming from those quarters—perhaps even from George H.W. Bush himself—had prevented Weston Edwards from completing his purchase.

This scandal may very well have been a well-crafted misdirection. As we will see, the backers of Fail did indeed have ties to Bush, and also to the same network of institutions that orbited Edwards’ troubled efforts. Even stranger is the fact that a number of institutions involved loopback to the PROMIS affair in which Robert Maxwell had played such a central part.