«Bluebonnet» was name given to fifteen Texas savings and loan institutions, bundled together and sold-off by federal regulators at the tail-end of the savings and loans crisis that rocked the United States in the late 1980s. For reasons that remain murky, Bluebonnet became the subject of intense interest by a number of intriguing individuals. As noted in Part 1 of this two-part article, this may have had something to do with the fact that the multiple thrifts that were consolidated into Bluebonnet had earlier been active in a sprawling «daisy chain» of bad loans, real estate transactions and money laundering. This hot money network was overseen and administered a very unusual coterie of conmen who had ties to powerful political figures in Texas and beyond, as well as to organized crime and the CIA.

When the fifteen S&Ls were on the auction block, among those who attempted to acquire them included figures linked to major nodes in this daisy chain—and they brought with them Robert Maxwell. Maxwell, at the time, was embarking on his effort to build an American business empire. Far from the curious appearance of a ruthless businessman hoping to capitalize on the crisis, Maxwell’s ill-fated attempt to purchase Bluebonnet was dependent on his deep ties to the state of Texas, ties that were intimately connected to the criminal and intelligence-linked underworld in which the controversial media mogul moved.

Maxwell’s departure from the Bluebonnet scene was by no means the end of the intrigue surrounding the thrift. Arriving soon after his exit was an insurance man with a history of fraud, and a revolving cast of suspect backers, all of whom had played supporting roles in a number of clandestine dealings that defined the corruption of the 1980s.

Bluebonnet, Round 2: A Widening Gyre

The man who ultimately secured ownership of Bluebonnet Savings, James M. Fail, got his start in the world of finance working in Alabama’s insurance industry. Among the various entities that he controlled included United Securities Holdings, the parent company of the Public National Life Insurance Company of Birmingham. Public National, in turn, managed numerous insurance concerns, running from life to industrial insurances. By 1971, it boasted over $72 million in assets.

Fail, it seems, was also familiar with fraud. In 1976, he transferred assets from Public National to a shell company, Modern Home Life Insurance. Along the way, he may have overstated the value of these assets to generate cash flow. That same year, Fail pleaded guilty in a securities fraud suit that targeted one of the officers of his companies.

By the late 1970s, Fail consolidated his various holdings together under the auspices of the Lifeshares Group, and began a march across the United States, accumulating along the way more and more companies to bundle under this umbrella. Subsidiaries of Lifeshares sprouted up in Nebraska, Texas, Arizona, Illinois and Maryland. Somewhere along the way, Fail relocated his base of operations to Phoenix, Arizona, and became acquainted with a man whose ties to powerful political forces generated a firestorm of controversy over Bluebonnet: lobbyist and Republican party insider Robert J. Thompson. “It is not clear,” notes the Congressional report on Bluebonnet, “how Fail and Thompson came together.”

Born in Oklahoma, Robert Thompson was the son of Victor Thompson, the longtime president of Utica National Bank. In 1982, Victor was accused by Congressional investigators of “knowingly concealing loan losses and deceiving investors” when it became known that Utica held a number of loans for Penn Square Bank. Penn Square, based in Oklahoma City, had declared bankruptcy that year, which had set off a domino-effect of bank losses across the country. Thompson’s deceptive practices mirrored those of Penn Square: various investment advisors charged that the bank had offered them assurances about the financial institution’s financial footing.

Other, darker things may have been afoot at Thompson’s Utica National Bank. One of the bank’s major borrowers was Global International Airways, a Missouri-based aviation company overseen by Farhad Azima. In 1984, journalists working for the Kansas City Star revealed that Global International had been involved in the transport of arms to conflict hotspots across the globe, presumably with CIA approval. They had also uncovered Global International’s relationship to EATSCO, a shadowy freight forwarding company that was a front utilized by former CIA officers Ted Shackley, Thomas Clines and Edwin Wilson. In the mid-1980s, another Azima company called Race Aviation popped up in the Iran-Contra affair.

Reportedly, one of Global International’s pilots was Heinrich “Harry” Rupp, a confirmed arms broker who was convicted in 1988 for defrauding Colorado’s Aurora Bank (Rupp had been brought to Aurora by a relative of one of Adnan Khashoggi’s employees). Rupp might have also been tied into the Texas crowd discussed in Part 1. Documents drafted by Rebecca Sims, found in the Danny Casolaro papers, reference an allegation made by an unnamed source that Rupp and Robert Corson were hidden owners of a company called Roswell Imported Cars, Inc. Sims noted that one of Roswell’s directors was also the director of a Houston aviation company, Northwest Jet, that Corson was known to use.

Such connections immediately raise questions about potential ties between Robert Thompson and the world of intelligence, and, by extension, his relationship to James Fail’s successful Bluebonnet acquisition. What is certain is that Thompson was politically well-connected. In 1979, he served as chairman of the Tulsa County Republican Party, and for his efforts Thompson was made an aide to George H.W. Bush. Various press reports describe him as the Vice President’s Congressional liaison, and as a “special assistant” to President Ronald Reagan.

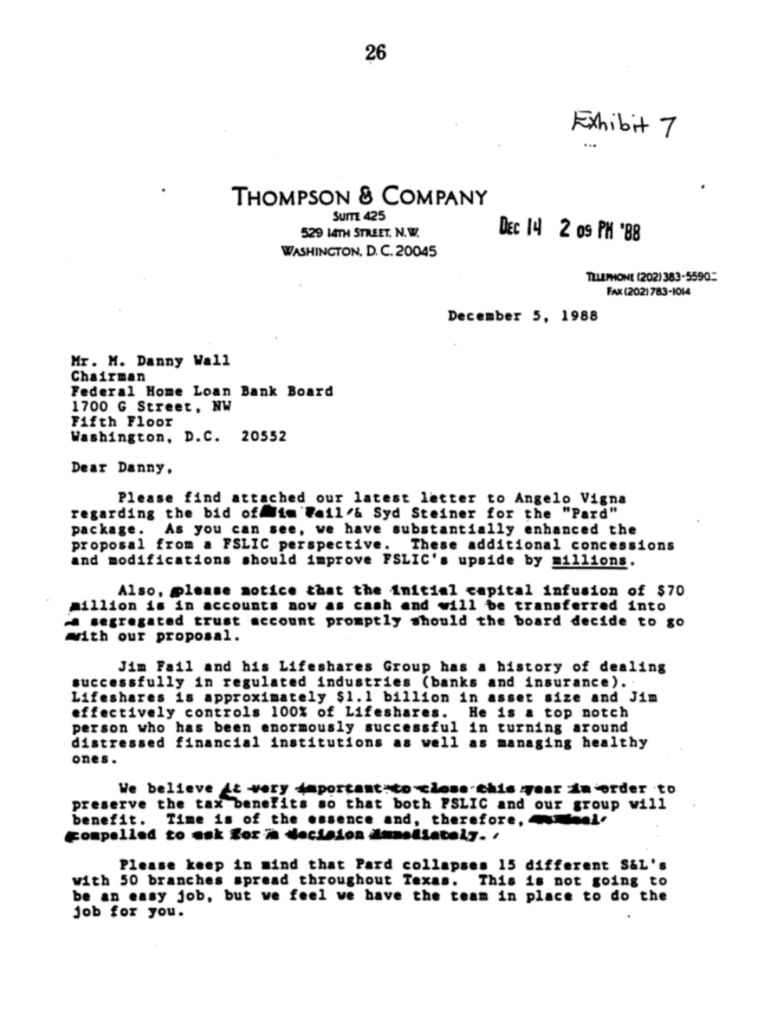

In the mid-1980s, Thompson left the White House to embark on a career as a lobbyist. The New York Times reported that “a central selling point of Thompson’s lobbying business was his relationship, including monthly get-togethers with the vice president.” Thompson was also a close friend of Daniel Wall, the nation’s top savings and loan regulator. The relationship between the two was so cozy that Thompson lobbied Wall directly over Fail’s attempts to purchase Bluebonnet, writing him letters beginning with “Dear Danny.”

Suspicions were soon raised that Thompson himself might have had an unseen financial interest in the Bluebonnet deal. As compensation for his efforts, Fail guaranteed a loan for Thompson from an Oklahoma bank, and in violation of Federal regulation, had the loan transferred from the bank to one of Fail’s insurance companies. Thompson used part of the money to invest in two ventures, one with California congressman Doug Bosco and the other with a former FDIC official in Oklahoma.

The ultimate deal that Thompson was able to craft for Fail was, quite frankly, ludicrous: he only put up $1,000 of his own money to buy the package of fifteen thrifts. Using his insurance companies as collateral, Fail secured $35 million in financing from Bankers Life, a subsidiary of I.C.H. Corp, an insurance giant headquartered in Louisville, Kentucky. A secondary loan was made to Fail, for the purposes of recapitalizing Bluebonnet, by the Capital National Corporation (CNC). CNC and I.C.H. were interrelated institutions, both owned by businessman Robert Shaw. At the time, Shaw was chairman of I.C.H., and president of CNC.

While I.C.H. was located in Kentucky, its principal banker was located elsewhere, in Dallas, Texas. The 1988/1989 edition of Major Companies of the USA shows that this bank was none other than M Bank, the bank that was so close to Robert Corson.

A 1987 report by CNN Money provided some details about what it described as “I.C.H. Corp’s ascent from nowhere.” The report notes that from 1982 through 1987, Shaw’s Kentucky insurance combine had been catapulted along a dizzying growth trajectory, with its balance sheet ballooning from $800 million to $8 billion in just 5 years. Part and parcel of I.C.H.’s rapid climb were the alliances that Shaw had forged. One of these alliances was with First Executive, the insurance giant overseen by Fred Carr. Before its spectacular fall in 1990, First Executive had been the top buyer of junk bonds peddled by Michael Milken; by some accounts, the value of these purchases totaled somewhere in the $40 billion range.

According to CNN Money, I.C.H. had purchased 9.9% of First Executive in October, 1986. At the time, First Executive was doing business with Imperial Savings of San Diego, then owned by the Gouletas family. As discussed in Part 1, the deep ties of the Gouletas family ranged from companies involved with Robert Corson to Jeffrey Epstein to Allan Tessler, attorney for Earl Brian.

Another I.C.H. ally was disgraced stock trader Ivan Boesky. Shaw had invested $10 million with Boesky in the mid-1980s. Boesky—who claimed to have worked undercover for the CIA in Iran in the 1970s—was, like Fred Carr and First Executive, closely tied to Milken and his junk bond peddling apparatus. The SEC charges that during the 1980s, “Milken supplied Ivan Boesky with capital and information, which Boesky used to take advantage of takeover bids and manipulate stocks to the benefit of both men.”

I.C.H. provided James Fail with the lion’s share of the capital he needed to complete the takeover of Bluebonnet. In light of its deep history with figures involved with Michael Milken, this paints an intriguing picture. While the junk bond story and the S&L story are often treated as separate tales of the runaway greed of 1980s finance, they are really the same story. There were the aforementioned business dealings between the Gouletas and First Executive, and the close ties that existed between Milken and the arch-S&L fraudster Charles Keating. Another case was the real estate investment firm Southmark, which was lodged within a deal-making triangle involving Keating and Milken.

Incredibly, at the time that I.C.H. began backing Fail, Shaw’s company was joined (almost quite literally) at the hip with Southmark. It is here that figures intimately connected to the PROMIS affair begin to bubble back up to the surface.

Meet Southmark

In the beginning, Southmark was known as Citizens and Southern Realty Investors. It was a real estate investment vehicle organized in the early 1970s by Citizens & Southern Bank, one of Atlanta’s largest banking houses. Citizens & Southern was certainly familiar with the darker side of politics: the institution had helped bankroll Bert Lance, Carter’s controversial Office of Management and Budget chief who was forced to step down under a cloud of scandal in 1977. It was Lance, in league with Jackson Stephens, who had first helped the Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI) penetrate the American banking system, thereby setting up key nodes for a truly global money laundering operation.

Around the time it was setting up the future Southmark, Citizens & Southern may have helped provide start-up capital to its employee, the CIA-trained Cuban exile Guillermo Hernandez-Cartaya, to form the World Finance Corporation (WFC). At the time of its collapse in the late 1970s, WFC was known to American law enforcement as a major player in illicit narcotics traffic and money laundering operations worldwide (Among those who availed themselves of the WFC’s services included Edward DeBartolo, the prominent shopping mall builder, reputed heir to Meyer Lansky’s criminal enterprise, and close business partner of Leslie Wexner). During this time, no major arrests or prosecutions were made against WFC principals. The reason? They were protected by the CIA.

In 1981, Southmark fell under the direction of Gene Phillips, who relocated its operations from Atlanta to Dallas, Texas. There, Phillips proceeded to build Southmark into what was known as a “vulture firm,” with a specialty in picking up the shattered pieces left in the wake of the S&L looting spree. Journalists Stephen Pizzo and Mary Fricker described these activities succinctly, stating: “Time and time again the company had turned up at the end of our investigation of a failed thrift… acquiring the troubled assets of those who had contributed to the failure of the institution.”

Feasting on the remains of economic failure isn’t always the most lucrative of gigs, and by the late 1980s, Southmark found itself in a perilous position. In dire need of cash flows, the company puzzled stock analysts when it announced a stock-swap plan with I.C.H. Corp. First proposed in 1987, the plan would effectively merge Southmark and I.C.H., which was – at the time – flush with capital thanks to its involvement with high-volume junk bond traders. This would have taken place on the eve of I.C.H.’s own forays into the world of dead S&Ls, through its bankrolling of the Bluebonnet purchase.

Besides I.C.H., other interesting figures could also be found in the gravitational pull of Southmark. One subsidiary of Southmark, Carlsberg Management, was run by developer (and prolific defaulter on S&L loans) G. Wayne Reeder. Among Reeder’s investments was a stake in a bingo parlor and casino on the Cabazon Indian Reservation in Indio, California—the site of a weapons development project carried out in conjunction with the Wackenhut Corporation. It was at the Cabazon reservation where at least some of the modifications of the PROMIS software were carried out.

A California law enforcement surveillance report on a meeting that took place in late 1981 at Cabazon between Wackenhut, representatives of various weapon development companies, and members of the Contra rebels reported that Reeder had arrived in the company of Earl Brian. Michael Riconosciuto, the weapons specialist who helped modify PROMIS, later stated that Reeder’s role in the operation was to source “clean money.”

The presence of Reeder at a subsidiary of Southmark is alarming enough, but an examination of the company’s owners besides Gene Phillips raises even more questions.

A 1985 Southmark annual report shows that 61.9% of its Series E Preferred Stock was held by AMI, Inc.—the Shreveport-based company owned by Herman Beebe and which had played such a central role in his S&L and insurance businesses. Indeed, Beebe and Southmark were a close-knit pair. His holdings in Southmark were leveraged to pay down debts he had to at least one S&L, though this was just the tip of the iceberg. Southmark was subsequently revealed to have done a staggering $90 million worth of business with Beebe, which included the purchase of various nursing homes owned by the fraudster.

The same annual report illustrates that another holder of Southmark’s Series E stock was the nursing home operator Beverly Enterprises, with 13.8% of the grand total. A major stakeholder in Beverly Enterprises, meanwhile, was Jackson Stephens’ Stephens, Inc. In turn, Stephens’ software company, Systematics, eventually contracted with Beverly Enterprises to service its data processing needs. This opens a potential linkage between Beverly Enterprises and the PROMIS affair—a possibility that was of great interest in the course of Bill Hamilton’s legal battle over the fate of Inslaw. As mentioned in Part 1 of this article, the modification of PROMIS held by Systematics was put to use in banks, for the dual purpose of tracking financial flows and facilitating money laundering.

A «memorandum for the record» drafted by Hamilton and his wife in connection with the case outlined the importance of Beverly Enterprises. They noted that principals of the company helped finance the 1974 Senate campaign of Earl Brian, and that by the early 1990s, Beverly Enterprises had become a user of a modified version of Inslaw’s PROMIS software.

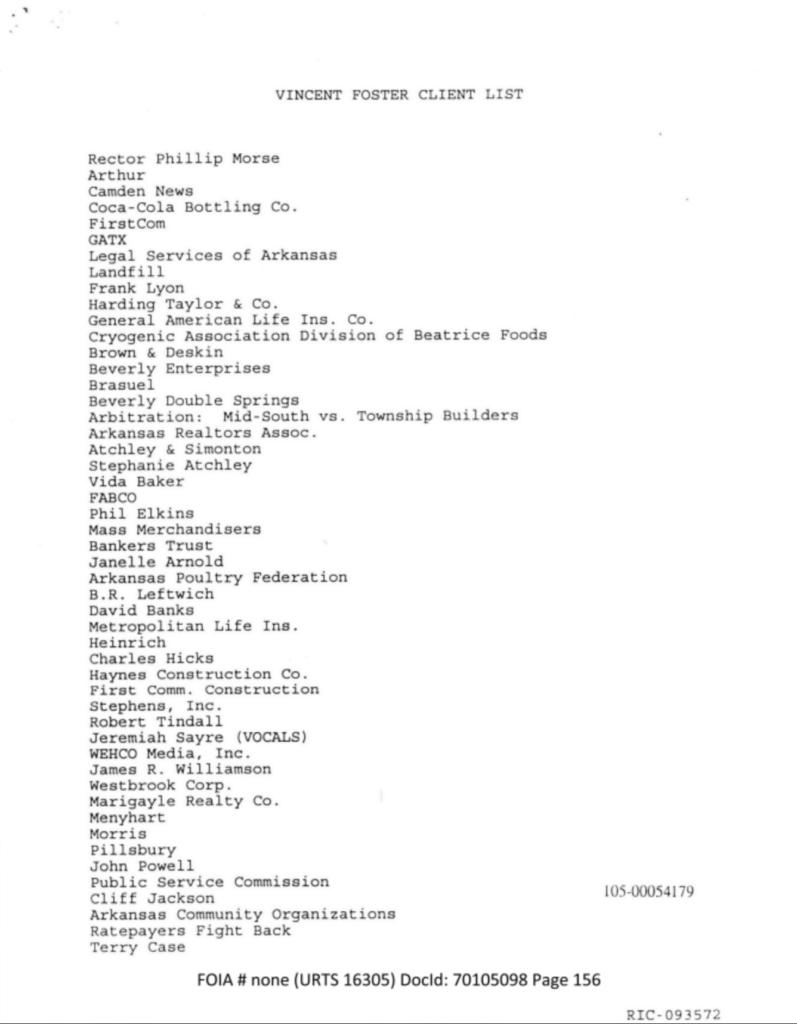

Intriguingly, both Beverly Enterprises and Beebe’s AMI appear on the attorney client list of Vince Foster, President Bill Clinton’s deputy White House counsel who died under suspicious circumstances on July 20th, 1993. Foster had previously been a partner at Arkansas’ prestigious Rose Law firm, which had boasted particularly close ties to the Clinton family’s political fortunes (Hillary Clinton herself had worked for the firm), and to Jackson Stephens’ stable of companies. While the interconnections between Foster, the Clintons, and Stephens have been heavily scrutinized over the years, little is known regarding what sorts of interactions Foster might have had with Beebe and his unruly gang of spooks, mobsters, and financial fraudsters.

It is quite possible that this tracks back, once again, to the PROMIS scandal. Ex-Forbes journalist Jim Norman, in his groundbreaking article «Fostergate«, describes how multiple sources had informed him that beginning sometime in the late 1970s, Foster had “been a silent, behind-the-scenes overseer on behalf of the NSA for a small Little Rock, Ark. (sic) bank data processing company”—that is, Stephens’ Systematics, Inc. Norman added that “Systematics has had close ties to the NSA and CIA ever since its founding, sources say, as a money-shuffler for covert operations.” If Foster was involved with intelligence community “money-shuffling,” this might help explain the connection to AMI; after all, Beebe was involved in effective money laundering on a colossal scale.

Towards the end of 1987, Southmark and I.C.H. Corp. abandoned their merger plans, citing “dissatisfaction… registered by the securities market” after concerns about regulatory roadblocks caused Southmark’s stock value to dip. Nonetheless, the two companies stated that they were committed to exploring “alternative methods of doing business together”. When Southmark finally went bust in 1989, I.C.H. was found to have “been listed as a $35 million creditor.” Southmark’s bankruptcy trustee stated that the “claim was bogus and should not be honored because Southmark and I.C.H. had engaged in a questionable stock swap to puff up their mutual balance sheets.”

Given the linkage between the Arkansas empire of Jackson Stephens and Southmark through Beverly Enterprises, it is possible that Stephens himself might have played some sort of role in this entire series of events. In 1987—the same year that Southmark and I.C.H. were exploring their merger—Stephens, Inc. raised $1.3 million for I.C.H., ostensibly for the purpose of enabling the company to acquire two life insurance companies. Several years later, in 1994, Stephens, Inc. announced that it was buying the controlling stake in I.C.H. held by Consolidated National Corporation—the same holding company owned by I.C.H.’s Robert Shaw that provided funds to James Fail to recapitalize Bluebonnet.

Everywhere one turns in the story of Bluebonnet, I.C.H., and Southmark, one bumps up against Jackson Stephens—and with him, the specter of PROMIS. Given the appearance of Robert Maxwell, the principal salesman of PROMIS abroad, in the Bluebonnet affair, it is clear that something very peculiar was happening with this package of beleaguered thrifts.

Dangling Threads: The Jersey Connection

There is circumstantial evidence that Robert Maxwell’s appearance in the Bluebonnet story wasn’t a one-off, momentary brush with the immense savings and loans swindle that took place across the United States. Incredibly, there are a number of overlaps between individuals operating in Maxwell’s extended network and figures involved in the pilfering of funds for ends that, many decades later, still remain murky.

Take the Florida land fraud, mentioned earlier, in which Robert Corson had played a key role. Central to that scam was a British attorney by the name of Keith Alan Cox, who had worked closely with the scam’s architect, Mike Adkinson. Adkinson was a Houston developer and builder close to the circles around Corson and Walter Mischer—and, reportedly, an “international arms dealer” who worked with a “group of Kuwaitis” to broker weapon sales to Iraq sometime in the early 1980s.

These arms dealings might hold the key to explaining how Adkinson became linked up with British attorney Keith Alan Cox. According to court filings drafted in connection with Adkinson’s land scam, Cox “represented a group of Kuwaitis who invested internationally through a multi-billion dollar company called Compendium Trust.” The filings also note that Compendium Trust had a “lending arm” called Sandsend Financial Consultants, Ltd. Sandsend, through Adkinson’s scheme, was able to spirit away large sums of money from Texas savings and loans, including funds from Corson’s Vision Banc.

Linda Minor notes that another player that bubbled up in the course of the scam was Southmark, though its involvement was ultimately blocked by regulators at the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation. Press reports from the period also show that Adkinson was fueling his real estate company, Development Group, Inc., with loans from San Jacinto Savings, one of Southmark’s subsidiaries. The man described in court records as San Jacinto’s “commercial lending officer” was Joseph Grosz, formerly employed by the Gouletas family.

Given the proximity of the Gouletas to Middle Eastern arms deals via their ties to Jeffrey Epstein, and to PROMIS sales (copies of which ended up in countries like Iraq), via their attorney Allan Tessler, it is worth asking to what degree the Florida land affair was being used to generate funds for clandestine activities.

Further details of Adkinson and Cox’s connections to the Middle East were provided by Rebecca Sims in an article for Covert Action Information Bulletin. According to Sims, in the early 1980s, Adkinson had partnered up with the Ahmad Al-Babtain Group, described as a consortium of “wealthy Kuwaitis”. Confusingly, Ahmad Al-Babtain was in fact Saudi in origin, though the group had extensive holdings in Kuwait. It appears that this is the same group that Cox was representing through Compendium Trust and Sandsend Financial Consultants. Pete Brewton notes that Cox stated in court that, at the time of the Florida land scam, Al-Babtain was no longer involved with the Isle of Jersey companies. This raises an important question: who, then, was Cox representing during his involvement with the looting of savings and loans?

Cox did have rather high-profile clients. On May 14th, 1992, while the fallout from the Florida fraud was still being battled out in court, Cox was appointed as a director of the board of the Oxford United Football Club. Since the early 1980s, Oxford United had been owned by Robert Maxwell, with the publishing magnate taking a term as the club’s chairman in 1982. By 1984, Ghislaine Maxwell and her brother, Kevin Maxwell, had taken positions on Oxford United’s board. Ghislaine held her spot until June 19th, 1991, while Kevin maintained his until May 14th, 1992—the day that the Maxwell estate sold their holdings in the club and Cox joined up as a new director. This suggests that Cox represented the interests of the buyers of Maxwell’s stake.

On May 15th, 1992, journalist Dan Atkinson ran an article in The Guardian titled “Jardine Matheson is buyer of Oxford football club.” In the article, Atkinson notes that the purchase of the Maxwell stake involved a convoluted nest of companies. The direct buyer was a British entity called Biomass Recycling Ltd., which in turn was controlled by an investment company called Energy Holdings Ltd. Energy Holdings, meanwhile, was “owned by a trust of which Jardine [Matheson]—an international group registered in the tax haven of the Bahamas—is the trustee.” Cox, then, could very likely have been acting on behalf of Jardine Matheson.

Jardine Matheson, which was once one of the great opium houses of British-controlled Hong Kong, has been the longtime haunt of the Keswick family, a prolific clan of merchants, bankers, and spies deeply embedded in the ruling classes in London and in Hong Kong (e.g., prominent members of the Keswick family populated the Special Operations Executive, a clandestine service organization operational during the Second World War). Recently, Unlimited Hangout reported that Jardine, which has long been accused of complicity in money laundering, may have been involved with Washington’s Farmington State Bank, an important node in the still-unfolding FTX imbroglio.

Robert Maxwell had his own ties to the Isle of Jersey, the small island and tax haven where savings and loan money vanished into the Cox-linked Compendium Trust and Sandsend Financial Consultants. The one-time chairman of his Pergamon Press was banker Sir Henry d’Avigdor-Goldsmid, formerly the head of the Anglo Israel Bank (a London affiliate of Israel’s Bank Leumi). Sir Henry had also acted as the chairman of the International Investment Trust Company of Jersey. This entity was slanted towards the interests of the Rothschild family: fixtures on the board included Jacob Rothschild, representing N.M. Rothschild of London, and George Karlweiss, an investment strategist in the employ of Edmond de Rothschild.

Then there is John Dick. Born to a Mennonite family in Canada, Dick’s climb to the top began in Colorado and he later set out for the Isle of Jersey sometime in the 1970s, where he resided in St. John’s Manor— “the finest house in Jersey,” as one journalist described it. His ascendancy was facilitated by deep inroads made into the British establishment, culminating in the 1980s with dealings with the powerful Peninsular & Steam Oriental Navigation Company (P&O). Together with his partner, William Pauls, Dick took control of European Ferries, a shipping company with global interests, and merged it into P&O, gaining along the way spots on the reformed company’s board. Dick and Pauls then tapped this capital to invest heavily in American real estate, with a trail of acquisitions that included the attempted acquisition of two of Colorado’s biggest ski resorts, Vail and Beaver Creek.

P&O, meanwhile, was closely tied to Keith Alan Cox’s likely employer, Jardine Matheson. During the 1970s, P&O and Jardine belonged to a corporate syndicate that controlled Southern Pacific Properties, a Hong Kong-based development company that specialized in hotels throughout Asia and the Pacific. Southern Pacific’s founder, Canadian businessman Peter Munk, had been backed early on by the powerful Keswick clans, the controlling force behind Jardine. Sometime during his world travels on behalf of Southern Pacific, Munk made contact with Saudi arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi; later, the pair would launch the fantastically wealthy—and politically-connected—Barrick gold mining company.

There were rumors that Dick himself was no stranger to the world of Saudi arms dealers. According to Richard Rossmiller (a serial S&L fraudster and participant in Mike Adkinson’s Florida land scam), Dick had “sold weapons to Saudi Arabia in the early 1980s”. Whatever the truth of the matter, Dick had certainly cultivated contacts in a world of powerful players, many of them in direct proximity to high-level arms dealing—and much more.

Press reports tell stories of Dick and William Pauls, strolling the streets of London “dressed in mink overcoats and black suits instead of the proper pinstripe suits”; the nickname granted to the pair was the “dark duo.” Some of Dick’s dark dealings apparently included helping himself to the open coffers of America’s savings and loans. Pete Brewton recounts that Dick had some manner of contact with Herman Beebe, though details of their business together remain murky.

What is clear is that Dick was particularly close to the circles around Silverado, the doomed Denver thrift where Neil Bush, son of George H.W. Bush, served on the board. During a divorce proceeding, Dick’s ex-wife told the court that Dick had aided Bill Walters—the man most responsible for Silverado’s free-fall collapse, and a close business partner of Neil Bush—in stashing some $20 million in funds in a Jersey bank.

This bank was likely Compendium Trust, the same bank tied to Keith Alan Cox and the Florida land fraud. A 2020 article in The Guardian notes that, over the course of Dick’s lengthy divorce battle, it was revealed that Compendium managed a private trust for Dick.

Further dealings of Dick’s were revealed by the 2015 leak of a trove of documents detailing the inner workings of La Hougue, a sprawling, long-running shadow financial apparatus controlled by Dick from his St. John Manor on the Isle of Jersey. Through Dick’s secretive machine, “wealthy clients in the U.S., U.K., and Europe engaged in elaborate schemes to minimize their taxes through legal loopholes, avoidance measures, dummy accounts, ginned-up debt, bogus client names, and painstakingly crafted document forgeries—an apparent specialty of La Hougue’s.”

The clients of Dick’s transnational laundromat included figures such as Igor Vishnevskiy, formerly the head of the Moscow offices for Marc Rich’s Glencore. More recently, Vishnevskiy has been involved in gold mining operations in Rwanda (Dick himself has acted as Rwanda’s ambassador-at-large, and travels with a Rwanda diplomatic passport). Another was Alexander Zhukov, the Russian-born and London-based investor and industrialist. Zhukov was accused of participating in an arms smuggling ring operating in Ukraine in the mid-1990s, leading to his arrest in Italy in 2001. He was subsequently acquitted on a technicality.

Other clients of Dick’s Jersey operation were members of the Maxwell family. To date, known involvement with La Hougue by the Maxwells dates to the mid-1990s, and many of the interactions concerned Telemonde, a media and telecommunications company founded by Kevin Maxwell. Before its inglorious decline in the wake of the bursting of the dotcom bubble, Telemonde—headquartered in the British Virgin Islands—had seemed like the makings of a giant, with a string of subsidiaries maintained from Bermuda to Oman. At its peak, Telemonde had a market capitalization of $500 million—but since the La Hougue revelations, this can now be understood as a clear-cut case of financial manipulation.

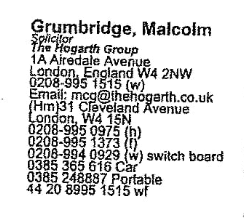

Through La Hougue, the Maxwells bought and swapped stock of Telemonde through a number of proxies, thus manipulating the company’s overall stock price. These transactions were negotiated with La Hougue by British attorney Malcolm Grumbridge. Described as the man acting “at the heart of the Maxwell’s opaque finances”, Grumbridge had been retained by Robert Maxwell in 1976, and had worked for him until his death. His name also appears in Jeffrey Epstein’s black book of contacts.

The stock price manipulation that Dick facilitated for Telemonde took place against the backdrop of Kevin Maxwell’s ambitious plan to become his “dad reincorporated”. Like his father, he clearly had a penchant for dubious financial schemes—and just as the older Maxwell had one shortly before his demise, Kevin went to work for shadow outfits operating in Eastern Europe and Russia. Among the eighty-plus companies he was affiliated with during the same time frame of the Telemonde affair was Nordex, a former KGB money laundering and capital-flight apparatus that Robert Maxwell himself had allegedly played a hand in setting up.

When the machinations of Nordex began to trickle out into the media during the 1990s, it was reported in the European press that the company had worked closely with Marc Rich and helped facilitate the commodity trader’s acquisition of newly-privatized assets in the former Soviet Union. As mentioned above, key figures in the Rich organization would emerge as clients of John Dick’s Jersey money laundromat.

Further research is required to determine if the relationship between the Maxwell clan and Dick’s operations on the Isle of Jersey preceded the mid-1990s. If such a relationship did exist, then perhaps more light could be shed on the mysterious appearance of Robert Maxwell in the American savings and loans crisis, when strange actors with even stranger motives descended on small lenders across the country, drained their assets, and left the American taxpayer holding the bag.