Today, the world’s economy no longer runs on oil, but data. Shortly after the advent of the microprocessor came the internet, unleashing an onslaught of data running on the coils of fiber optic cables beneath the oceans and satellites above the skies. While often posited as a liberator of humanity against the oppressors of nation-states that allows previously impossible interconnectivity and social organization between geographically separated cultures to circumnavigate the monopoly on violence of world governments, ironically, the internet itself was birthed out of the largest military empire of the modern world – the United States.

The ARPANET

Specifically, the internet began as ARPANET, a project of the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), which in 1972 became known as the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), currently housed within the Department of Defense. ARPA was created by President Eisenhower in 1958 within the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) in direct response to the U.S.’ greatest military rival, the USSR, successfully launching Sputnik, the first artificial satellite in Earth’s orbit with data broadcasting technology. While historically considered the birth of the Space Race, in reality, the formation of ARPA began the now-decades-long militarization of data brokers, quickly leading to world-changing developments in global positioning systems (GPS), the personal computer, networks of computational information processing (“time-sharing”), primordial artificial intelligence, and weaponized autonomous drone technology.

In October 1962, the recently-formed ARPA appointed J.C.R. Licklider, a former MIT professor and vice president of Bolt Beranek and Newman (known as BBN, currently owned by defense contractor Raytheon), to head their Information Processing Techniques Office (IPTO). At BBN, Licklider developed the earliest known ideas for a global computer network, publishing a series of memos in August 1962 that birthed his “Intergalactic Computer Network” concept. Six months after his appointment to ARPA, Licklider would distribute a memo to his IPTO colleagues – addressed to “Members and Affiliates of the Intergalactic Computer Network”– describing a “time-sharing network of computers” – building off a similar exploration of communal, distributed computation by John Forbes Nash, Jr. in his 1954 paper “Parallel Control” commissioned by defense contractor RAND – which would build the foundational concepts for ARPANET, the first implementation of today’s Internet.

Prior to the technological innovations explored by Licklider and his ARPA colleagues, data communication – at this time, mainly voice via telephone lines – were based on circuit switching, in which each telephone call would be manually connected by a switch operator to establish a dedicated, end-to-end analog electrical connection between the two parties. The RAND Corporation’s Paul Baran, and later ARPA itself, would begin to work on methods to allow formidable data communication in the event of a partial disconnection, such as from a nuclear event or other act of war, leading to a distributed network of unmanned nodes that would compartmentalize the desired information into smaller blocks of data – today referred to as packets – before routing them separately, only to be rejoined once received at the desired destination.

While certainly unbeknownst to the technologists at the time, this achievement of both distributed routing and global information settlement via data packets created an entirely new commodity – digital data.

A Brief History of Weaponized Financial Intelligence

Long before the USSR spooked the United States into formalizing ARPA due to fears of militarized satellite applications post-Sputnik launch, data brokers have played a significant role in warfare and specifically the markets surrounding military conflict. One well-known yet early example occurred during the Napoleonic wars in the 19th century, when the banking stalwart Rothschild family used carrier pigeons and horseback couriers to gain an information settlement edge related to battle outcomes, while speedily communicating with their traders back in London. These animal-driven technological exploits allowed Rothschild-affiliated brokers to place well-informed bets on the outcome of France’s warmongering to position themselves on the winning sides of large currency and commodity bets. This similar but modernized technique would later be employed by figures like commodity trader (and Mossad asset) Marc Rich in the 1980s, who used satellite phones and optical imagery techniques to track and relay oil tanker flows between nations, giving his trades an asymmetric advantage when dealing within the active petrodollar system. Similarly, Louis Bacon’s Moore Capital achieved 86% gains in its first year largely due to correctly anticipating Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait due to astute intelligence sharing from military sources, and correctly going long on oil prices while shorting stocks.

As the front of modern warfare slowly evolved from direct military action into weaponized financial speculation, the market for data became just as valuable as the defense budget itself. It is for this reason that the necessity of sound data emerged as the foremost issue of national security, leading to a proliferation of advanced data brokers coming out of DARPA and the intelligence community, akin to the 21st century’s Manhattan Project.

The San Jose Project: Google, Facebook, and PayPal

Exemplified by the creation of the CIA’s venture firm, In-Q-Tel, and the proliferation of Silicon Valley-based venture firms coalescing on Sand Hill Road in Palo Alto, CA, the financialization of a new crop of American data brokers was complete. The first firm to grace Sand Hill Road was Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, better known as KPCB, which participated in funding internet pioneers Amazon, AOL, and Compaq, while also directly seeding Netscape and Google. KPCB partners have included such government stalwarts as former Vice President Al Gore, former Secretary of State Colin Powell, and Ted Schlein – the latter being a board member of In-Q-Tel and member of the NSA’s advisory board. KPCB also had an intimate connection with internet networking pioneer Sun Microsystems, best known for building out the majority of network switches and other infrastructure needed for a modern broadband economy.

Outside of the obvious need for network infrastructure for a data economy, an early Sun employee and eventual KPCB partner Bill Joy patented a widely-used distributed file system software known as NFS, or Network File System. Sun also established a public-sector focused subsidiary known as Sun Federal at the start of the 1990s. By 1991, Sun Federal was responsible for more than half of the workstations ordered by local, state and federal governments in the country. Perhaps the world’s most famous data broker, Google, whose founders both came out of Stanford University, was seeded by former Sun Microsystems founder Andy Bechtolsheim and his partner at the Ethernet switching company Granite Systems (later acquired by Cisco), David Cheriton, with Google’s most iconic CEO, Eric Schmidt, being the former CTO of Sun Microsystems.

The emergence of Silicon Valley out of the academic circuit in Northern California was no accident, and in fact was directly influenced by an unclassified program known as the Massive Digital Data Systems (MDDS) project. The MDDS was created with direct participation from the CIA, NSA, and DARPA itself within the computer science programs at Stanford and CalTech, alongside MIT, Harvard and Carnegie Mellon. According to reporting from Quartz, this research, with clear national security implications, would be largely “funded and managed by unclassified science agencies like NSF (the National Science Foundation) allowing “the architecture to be scaled up in the private sector” in an attempt “to achieve what the intelligence community hoped for.” The MDDS white paper was released in 1993, and over a few years, more than a dozen grants of several million dollars each were distributed via the NSF in order to capture the most promising efforts, ensuring that those efforts would become intellectual property controlled by the United States regulatory regime.

“Not only are activities becoming more complex, but changing demands require that the IC [Intelligence Community] process different types as well as larger volumes of data,” reads the MDDS white paper. “Consequently, the IC is taking a proactive role in stimulating research in the efficient management of massive databases and ensuring that IC requirements can be incorporated or adapted into commercial products. Because the challenges are not unique to any one agency, the Community Management Staff (CMS) has commissioned a Massive Digital Data Systems [MDDS] Working Group to address the needs and to identify and evaluate possible solutions.”

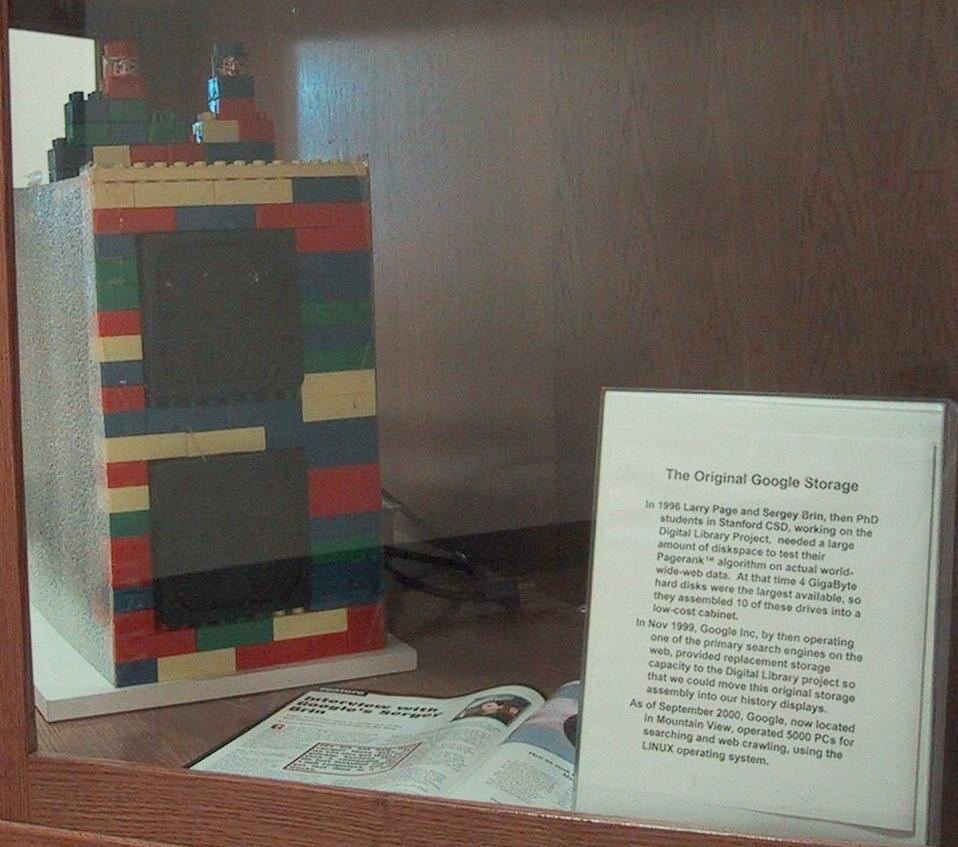

The first unclassified briefing for scientists was titled “birds of a feather briefing” and was formalized during a 1995 conference in San Jose, CA, which was titled the “Birds of a Feather Session on the Intelligence Community Initiative in Massive Digital Data Systems.” That same year, one of the first MDDS grants was awarded to Stanford University, which was already a decade deep in working with NSF and DARPA grants. The primary objective of this grant was to “query optimization of very complex queries,” with a closely-followed second grant that aimed to build a massive digital library on the internet. These two grants funded research by then-Stanford graduate students and future Google cofounders, Sergey Brin and Larry Page. Two intelligence-community managers regularly met with Brin while he was still at Stanford and completing the research that would lead to the incorporation of Google, all paid for by grants provided by the NSA and CIA via MDDS.

While often not discussed when describing Google’s origin story, the principal investigator for the MDDS grant specifically named Google as directly resulting from their research: “Its core technology, which allows it to find pages far more accurately than other search engines, was partially supported by this grant,” wrote Jeffrey Ullman. Furthering this concept, Stanford’s Infolab website explains that “the development of the Google algorithms was carried on a variety of computers, mainly provided by the NSF-DARPA-NASA-funded Digital Library project at Stanford.”

Google would certainly set the standard for success during the first Dot Com bubble. Yet, shortly following their incorporation, two similar Silicon Valley companies with significant ties to the intelligence community would also emerge from colleges affiliated with the MDDS – PayPal and Facebook.

PayPal was launched in December 1998 as Confinity Inc. by founders Peter Thiel and Max Levchin, alongside Luke Nosek and Ken Howery. The company sought to provide financial institutions with the technological ability to make mobile and online economic transactions secure using cryptography – technology at the time heavily regulated by the United States. Thiel had graduated from Stanford Law School in 1992, and then had a brief stint at the Wall Street law firm Sullivan & Cromwell – a legal practice long known for its ties to the U.S. intelligence apparatus. Early on, Confinity Inc. operated out of 165 University Avenue in Palo Alto, CA at, a building that had previously housed Google during their “formative years,” after previously sharing an office with Elon Musk’s X.com.

It was also during these formative years that the PayPal team worked closely with the intelligence community. Levchin later stated in an interview with Charlie Rose that: “I think the government working with a private sector is a great thing. When we were working on security and anti-fraud measures at PayPal, we collaborated with every imaginable three and four-letter agency and those were some of the best, most productive relationships I’ve had as a business person…I think if the private sector can help them, we should.” Due to an unprecedented viral growth of their user base, PayPal engineers spent much of the formation period of the company building software to help identify fraudulent transactions to mitigate the growing costs of rampant fraud in the ecosystem, eventually developing an adaptive algorithm named “Igor” after a Russian criminal that would frequently taunt PayPal’s fraud department.

In 2003, a year after PayPal was sold to eBay, Thiel approached Alex Karp, a fellow alumnus of Stanford with a new venture concept: “Why not use Igor to track terrorist networks through their financial transactions?” Thiel took funds from the PayPal sale to seed the company, and after a few years of pitching investors, the newly-formed Palantir received an estimated $2 million investment from the CIA’s venture capital firm, In-Q-Tel. Palantir’s co-founders consulted with John Poindexter during his tenure as head of DARPA’s then-embattled Total Information Awareness in efforts to privatize the controversial surveillance program. In 2020, Intelligencer spoke with a former intelligence official who was involved in the investment who claimed the CIA had hoped that “tapping the tech expertise of Silicon Valley” would allow it to “integrate widely disparate sources of data regardless of format.”

As of 2013, Palantir’s client list included “the CIA, the FBI, the NSA, the Centre for Disease Control, the Marine Corps, the Air Force, Special Operations Command, West Point and the IRS” with around “50% of its business” coming from public sector contracts. Palantir is closely connected to the U.S. government, but its financial spin-off, Palantir Metropolis, is focused on providing “analytical tools” for “hedge funds, banks and financial services firms” to outsmart each other. As The Guardian reports: “Palantir does not just provide the Pentagon with a machine for global surveillance and the data-efficient fighting of war, it runs Wall Street, too.”

Facebook, not unlike Palantir, was one of the vehicles used to privatize controversial U.S. military surveillance projects after 9/11, having also been birthed out of one of the MDDS partners, Harvard University. PayPal and Palantir co-founder Peter Thiel became Facebook’s first significant investor at the behest of file-sharing pioneer Sean Parker, whose first contact with the CIA took place at age 16. What Facebook became after the involvement of Thiel and Parker bore such an uncanny resemblance to another shuttered DARPA project of the same era, known as LifeLog, that LifeLog’s architect and project manager at DARPA has even noted the direct parallels. One of these parallels, though left unmentioned by former DARPA project managers, is the fact that Facebook launched the very same day that LifeLog was shut down. Facebook’s long-standing ties to the military and intelligence communities go far beyond its origins, including revelations about its collaboration with spy agencies as part of the Snowden leaks and its role in influence operations – some have even directly involved Google and Palantir.

An unspoken outcome of the global proliferation of Facebook was the sly, roundabout creation of the first digital ID system – a necessity for the coming digital economy. Users would set up their profiles by feeding the social network with a plethora of personal information, with Facebook being able to use this data to generate large webs of connectivity between otherwise unknown social groups. There is even evidence that Facebook generated placeholder accounts for individuals that appeared in user data but did not have a profile of their own. Both Google and PayPal would also use similar digital identification methods to allow users to sign into other websites, creating interoperable identification systems that could permeate the internet.

A similar evolution is occurring in the financial sector, as data broker social networks – including Facebook and Musk’s X (formerly Twitter) – are posturing themselves as the future of financial service companies. This idea makes more sense when you consider that money itself is a communication technology, and can easily be built into existing communication platforms – especially ones driven by user data and identity systems. We are simultaneously seeing financial services, such as the largest dollar stablecoin issuer Tether – with excessive ties to PayPal – spending millions on investments in next generation data broker technology. Tether has recently funded the Earth observation/Satellite-as-a-service company Satellogic, the brain chip company Blackrock Neurotech, AI-computation firm Northern Data, and even Rumble, a Thiel-funded competitor to Google’s YouTube.

From Public-Private, to Private-Public

As outlined above, it is clear that the public sector’s intelligence community used the veil of the private sector to establish financial incentives and commercial applications to build out the modern data economy. A simple glance at the seven largest stocks in the American economy demonstrate this concept, with Meta (Facebook), Alphabet (Google), and Amazon – with founder Jeff Bezos being the grandson of ARPA founder Lawrence Preston Gise – leading the software side, and Microsoft, Apple, NVIDIA and Tesla leading the hardware component. While many of these companies have egregious ties to the intelligence community and the public sector during their incubation, now these private sector companies are driving the globalization and national security interests of the public sector.

The future of the American data economy is firmly situated between two pillars – artificial intelligence and blockchain technology. With the incoming Trump administration’s close advisory ties to PayPal, Tether, Facebook, Palantir, Tesla and SpaceX, it is clear that the data brokers have returned to roost at Pennsylvania Avenue. AI requires massive amounts of sound data to be of any use for the technologists, and the data provided by these private sector stalwarts is poised to feed their learning modules – surely after securing hefty government contracts. Private companies using public blockchains to issue their tokens generates not only significant opportunities for the United States to address its debt problem, but simultaneously serves as a “boon in surveillance”, as stated by a former CIA director.

Within the Trump administration’s embracing of the blockchain – itself the final iteration of the public-private commercialization of data, despite its libertarian posturing – reveals the culmination of a decades-long technocratic dialectic trojan horse. Nearly all of the foundational technology needed to push the world into this new financial system was cultivated in the shadows by the military and intelligence community of the world’s largest empire. While technology can surely offer solutions for greater efficiency and economic prosperity, the very same tools can also be used to further enslave the citizens of the world.

What once appeared as a guiding light beckoning us towards free speech and financial freedom has revealed itself to be nothing but the shine of Uncle Sam’s boot making its next step.

Mark takes us through the origins of “Mr. Global’s” minion fronts who have developed the internet. It’s not just Bitcoin that was a huge Trojan Horse, but the Internet itself as well. To quote from Whitney’s review (called The “AI Revolution”: The Final Coup d’Etat?”) of Kissinger et al.’s book on AI quoting the “insufferable” minion Harrari: “[Dataism] is now mutating into a religion that claims to determine right and wrong [aka Ethics/Morality]. The supreme value [aka Ultimate End] of this new religion is ‘information flow.’ If life is the movement of information, and if we think that life is good, it follows that we should extend, deepen and spread the flow of information in the universe. According to Dataism, human experiences are not sacred and Homo sapiens isn’t the apex of creation… Humans are merely tools for creating the Internet-of-All-Things, which may eventually spread out from planet Earth to cover the whole galaxy and even the whole universe. This cosmic data-processing system… will be everywhere and will control everything, and humans are destined to merge into it.” Thus, it’s not just Bitcoin, or the Internet that is Mr. Global’s trojan horse but higher still, it’s his domination of and sacrifice of humanity to his own push to dominate “the whole galaxy.”

F#ck!ng outstanding research Mark, but I am becoming tremendously frustrated at not seeing IBM named and blamed, must all be good people in their ranks :S or good at covering their butts.

Thanks for bringing all this together, Mark. Ironically, these government-backed tech tycoons are partnering with the anti-government right-wing Republican crowd. None of these tech founders are anything close to “libertarians,” as they claim. They are really Neofascists oppressing the people they were meant to unleash from the tyrant government via the internet. Biden’s recent warning about the “incoming tech oligarchy” could have only been delivered by a sociopath since he did everything in his power to enrich the principles of the tech oligarchy. Even his TikTok ban enriched Zuckerberg and Musk, who hate competition. I find the TT user’s transition to Red Note, a deeper Chinese-controlled app, hilarious. I am sure Zuck and Musk thought they would flock back to their apps.

While everybody is paying attention to the media whore, Musk, I’ve been warning everyone that Thiel and Vance are the ones to keep an eye on under Trump. Donald wants to play golf and watch Fox News all day. Thiel and Vance will be running the operations.

You hit the nail on the head by “Thiel and Vance are the ones to keep an eye on under Trump.” There is a Pharaoh and Moses inside each of us.

Lions! Tigers! and Bears! Oh my! I can almost feel the thread like tendrils of Dataism trying to invade my body and take it over like the Invasion Of The Body Snatchers. Being aware of this is the fist step to trying to stop this and I thank Mark and commenters for all of your insight.

Both the links in this sentence are broken — This site can’t be reached db.cs.pitt.edu

“While often not discussed when describing Google’s origin story, the principal investigator for the MDDS grant specifically named Google as directly resulting from their research: “Its core technology, which allows it to find pages far more accurately than other search engines, was partially supported by this grant,” wrote Jeffrey Ullman”

Any chance of a backup link?

The internet is the tool of oppression. It is a NET. They will disappear all information that exposes them.