During our investigation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the disingenuous use of language to sell SDGs to an unsuspecting public has emerged as a common theme.

The United Nations (UN) claims the purpose of SDG16 is to:

Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels.

If we accept the supposition that «sustainable development» is global development that meets the needs of the world’s poor, then a reasonable person is unlikely to disagree with this stated objective.

But helping the poor is not the purpose of SDG16.

The real purpose of SDG16 is threefold: (1) empower a global governance regime, (2) exploit threats, both real and imagined, to advance regime objectives; and (3) force an unwarranted, unwelcome, centrally controlled global system of digital identity (digital ID) upon humanity.

We find the UN’s digital ID objective tucked away in its SDG Target 16.9:

By 2030, provide legal identity for all, including birth registration.

While SDG16 doesn’t allude specifically to «digital» ID, that is what it means.

As we shall see, the SDG16 target indicators don’t reveal the truth, either. For example, the only «indicator» to measure SDG16.9 progress (16.9.1) is:

[The] proportion of children under 5 years of age whose births have been registered with a civil authority, by age.

You might therefore think the task of «providing legal identity» would primarily fall to said «civil authorities.» That is not the case.

Within the UN system, all governments (whether local, county, provincial, state, federal) are «stakeholder partners» in a global network comprised of a wide-ranging gamut of public and private organisations. Many of these are explicitly backed by or housed at the UN, and all of them are pushing digital ID as the key mechanism to achieve SDG16.

This aspect of SDG16 will be more fully explored in Part 2.

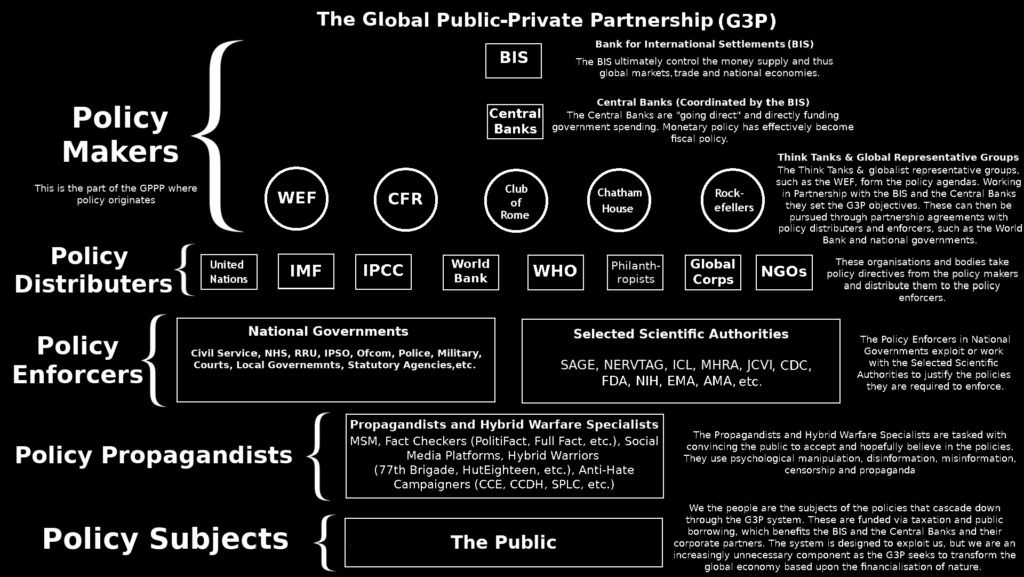

There is a term that this worldwide amalgam of organisations often uses to describe itself: it is a global public-private partnership—G3P, for short.

The G3P is toiling tirelessly to create the conditions necessary to justify the imposition of both global governance «with teeth» and its prerequisite digital ID system. In doing so, the G3P is inverting the nature of our rights. It manufactures and exploits crises in order to claim legitimacy for its offered «solutions.»

The G3P comprises virtually all of the world’s intergovernmental organisations, governments, global corporations, major philanthropic foundations, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and civil society groups. Collectively, these form the «stakeholders» implementing sustainable development, including SDG16.

Digital ID will determine our access to public services, to our Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) wallets, to our «vaccine» certificates—to everything, even the food and beverages we’re allowed to buy and consume.

Wary citizens are watchful for potential abuse of digital ID by their authorities. In countries where a national digital ID card is not welcome, such as in the UK, the G3P solution is to construct an «interoperable» system that links various digital ID systems together. This «modular platform» approach is designed to avoid the political problems that the official issuance of a national digital ID card would otherwise elicit.

Establishing SDG16.9 global digital ID is crucial for eight of the seventeen UN SDGs. It is the linchpin at the centre of a global digital panopticon that is being devised under the auspices of the UN’s global public-private partnership «regime.»

Human Rights versus Inalienable Rights

For reasons that will become apparent, it is important that we fully understand the UN’s concept of «human rights.»

Human rights are mentioned nine times in the United Nations Charter.

A key document referenced by the UN Charter is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was first accepted by all members of the United Nations on December 10, 1948.

The preamble of the Declaration recognises that the «equal and inalienable rights» of all human beings are the «foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world.» After that, «inalienable rights» are never again mentioned in the entire Declaration.

«Human rights» are nothing like «inalienable rights.»

Inalienable rights, unlike human rights, are not bestowed upon us by any governing authority. Rather, they are innate to each of us. They are immutable. They are ours in equal measure. The only source of inalienable rights is Natural Law, or God’s Law.

No one—no government, no intergovernmental organisation, no human institution or human ruler—can ever legitimately claim the right to grant or deny our inalienable rights. Humanity can claim no collectiveauthority to grant or deny the inalienable rights of any individual human being.

Beyond the preamble, the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) concerns itself exclusively with «human rights.» But asserting, as it does, that human rights are some sort of expression of inalienable rights is a fabrication—a lie.

Human rights, according to the UDHR, are created by certain human beings and are bestowed by those human beings upon other human beings. They are not inalienable rights or anything close to inalienable rights.

Article 6 of the UDHR and Article 16 of the UN’s 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (where, again, inalienable rights are mentioned just once in the preamble), both decree:

Everyone has the [human] right to recognition everywhere as a person before the law.

Note: We put «[human]» in brackets in the above quote (and in other UN quotes below) to alert readers that these documents are not referring to inalienable rights.

While the respective Articles 6 and 16 sound appealing, the underlying implications are not. Both articles mean that «without legal existence those rights may not be asserted by a person within the domestic legal order.»

As we shall see, the ability to prove one’s identity will become a prerequisite for «legal existence.» Thus, in a post-SDG16 world, persons without UN-approved identification will be unable to assert their «human rights.»

Under the UN’s system of «human rights,» human beings are not considered to have any inalienable rights. For, as the UN would have it, our alleged «human rights» can be observed only if we comply with the current «legal order.» That «order» is conditional. And it is subject to constant change.

Article 29.2 of the UDHR states:

In the exercise of his [human] rights and freedoms, everyone shall be subject only to such limitations as are determined by law solely for the purpose of securing due recognition and respect for the [human] rights and freedoms of others and of meeting the just requirements of morality, public order and the general welfare in a democratic society.

Article 29.3 of the UDHR states:

These [human] rights and freedoms may in no case be exercised contrary to the purposes and principles of the United Nations.

In plain English: We are only allowed to exercise our alleged human «rights» subject to the diktats of governments, intergovernmental organisations and other UN «stakeholders.»

The bottom line, then, is that what the UN calls «human rights» are not «rights» of any kind at all. They are government and intergovernmental permits by which our behaviour is controlled. Thus, by the UN’s definition, «human rights» are the antithesis of «inalienable rights.»

But remember, we have been informed—in the preamble of that same Declaration—that «inalienable rights» are the «foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world.» Please bear this point in mind as we continue to unravel the UN’s SDG16 plot against humanity.

Human Rights as Policy Tools

It is common practice among the UN and its partners, such as the World Economic Forum (WEF), to view crises as opportunities. The WEF admitted, for instance, that the COVID-19 «pandemic» was «a unique window of opportunity.»

The UN said the same thing. After one of its «specialist agencies,» the World Health Organisation (WHO), declared a global pandemic on 11 March 2020, the UN published COVID-19 and Human Rights, in which it said:

How we respond today, therefore, presents a unique opportunity to course-correct and begin to tackle long-standing public policies and practices that have been harmful for people and their human rights.

That both the UN and the WEF perceived COVID-19 as a unique opportunity to «reset» or «course-correct» should surprise no one. The WEF is a strategic partner of the UN, and both are equally committed to «accelerat[ing] the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.»

It is within this frame of reference that the UN’s perception of what it calls «human rights» takes on a peculiar dimension:

The United Nations has available a powerful set of tools, in the form of human rights, that equip States and whole societies to respond to threats and crises in a way that puts people at the centre.

Here, the UN and its partners are assuming the authority to define «human rights» and to treat them as mere policy tools. Note how it says that «States» (capital «S») can use these tools to put people at the centre of a crisis or threat response. The UN is insinuating that, if respected, «human rights» should shape a humanitarian policy response to a threat or crisis.

However, the UN contradicts itself in the same document. Later on, it suggests that a policy response to a crisis or threat can justify discounting human rights:

Human rights law recognizes that national emergencies may require limits to be placed on the exercise of certain human rights. The scale and severity of COVID-19 reaches a level where restrictions are justified on public health grounds.

This statement about restrictions to human rights is far-and-away removed from the concept of inalienable, or «natural,» rights, which are inviolable and immutable. Thus, by placing «human rights» at the centre of a policy response to a threat or a crisis, the UN and its partners are exploiting the unique opportunity to not only redefine «human rights» but to ignore those supposed rights whenever they deem it necessary.

It gets worse. Instead of respecting our actual rights and defining them accurately, the UN proceeds to outline how these new «policy tool rights» can be used by legislators. It adds components to its alleged «human rights» structure that otherwise have nothing to do with rights:

People are being asked to comply with extraordinary measures, many severely restricting their human rights. [. . .] Securing compliance depends on building trust, and trust depends on transparency and participation.

Translation: We are going to take away your human rights. We know you will readily comply as long as we justify our restrictions on public health grounds and persuade you that this is our sole goal. Just trust us.

The Cambridge Dictionary defines the verb «to trust» as «to hope and expect that something is true.» When you take something on trust, it says, you «believe that something is true although you have no proof.» It also says that «to trust» is «to believe that someone is good and honest and will not harm you, or that something is safe and reliable. . . .»

In its COVID-19 and Human Rights document, the UN declares that our compliance can be secured through our unquestioning acceptance of whatever we are told by the «authorities.»

Consequently, anything that erodes «trust» in the UN—in its ideas, policy agendas, agencies and «stakeholder partners»—the document calls «disinformation» or «misinformation.»

According to that document, the UN welcomes censorship of speech:

The crisis raises the question how best to counter harmful speech while protecting freedom of expression. Sweeping efforts to eliminate misinformation or disinformation can result in purposeful or unintentional censorship, which undermines trust. [. . .] While flags and takedowns of misinformation are welcome, giving greater prominence to reliable information needs to be the first line of defence.

The dichotomy the UN faces is clear. On the one hand, the organisation is keen for its government partners to flag and take down supposedly wrong information by applying new derivative labels like «harmful» and to decree by fiat what constitutes «disinformation»—all of this evidence of its desire to promote censorship to curtail free speech. On the other hand, it is paradoxically claiming that it values «freedom of expression.» This hypocritical nonsense is a bald-faced attempt to avoid eroding the public «trust» it desperately seeks.

But criticism of the UN, which of course the UN labels «disinformation,» is often justified. For example, in COVID-19 and Human Rights the UN wrote:

COVID-19 is showing that universal health coverage (UHC) must become an imperative. [. . .] UHC promotes strong and resilient health systems, reaching those who are vulnerable and promoting pandemic preparedness and prevention. SDG 3 includes a target of achieving UHC.

As previously discussed at Unlimited Hangout, what the UN is saying here is patently false. The UN’s SDG3 pursuit of Universal Health Coverage during COVID-19 destroyed relatively strong and resilient health systems. It propelled many developing and emerging economies into ever-greater debt. It degraded health outcomes. There was no «imperative» to establish UHC in order to tackle COVID-19. Doing so delivered results that were contrary to the UN’s claimed objective: the «sustainable development» of healthcare in the Global South.

However, as we have noted elsewhere, shackling emerging economies with debt is seen by the UN as a means of securing those countries’ compliance with the policy goals tucked inside its Agenda 2030 SDGs. Some of those goals seek to financialize the natural resources of targeted nations while eroding their national sovereignty.

We also know that the WHO, as a key stakeholder of the UN’s SDG3 (aka UHC) policy agenda, is currently leading the development of the proposed Pandemic Preparedness Treaty. (Its full name is the International Treaty on Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness and Response. Its short name is the Pandemic Accord.) Numerous investigators and commentators have already shown that this treaty portends the erosion of national sovereignty and the loss of both our so-called «human» and our alleged political rights.

Furthermore, the UN is itself often the purveyor of disinformation. For example, its current Secretary-General, Antonio Guterres, made the following Tweet:

Human rights are the foundation of human dignity. As we mark 75 years of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and help to promote a world of dignity, freedom and justice.

This is a blatantly false assertion. The Declaration clearly states that «inalienable rights»—not «human rights»—are the «foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world.» Thus, the Secretary-General of the United Nations was spreading disinformation. He was deceiving the public about the implications of one of the UN’s own seminal documents.

The WHO is also amending the International Health Regulations (IHR). The process of amending the IHR «runs in parallel» with the WHO’s work on the aforementioned Pandemic Accord. Both the IHR and the Pandemic Accord will be binding on all 193 UN signatory member states.

The current proposed amendments to the IHR illustrate how «crises» provide unique opportunities for the UN and its partners to control populations—through purported «human rights»—by exploiting those «rights» as «a powerful set of tools.»

Here is one example of the proposals being put forth: The WHO wishes to remove the following language from IHR Article 3.1:

The implementation of these Regulations shall be with full respect for the dignity, human rights and fundamental freedoms of persons.

It intends to replace that regulatory principle with:

The implementation of these Regulations shall be based on the principles of equity, inclusivity, coherence and in accordance with the common but differentiated responsibilities of their States Parties, taking into consideration their social and economic development.

This proposed amendment signifies that the UN and its partners wish to completely ignore the UN’s own Universal Declaration of Human Rights whenever any of these agencies declares a new «crisis» or identifies a new «international threat.» This exemplifies the «course-correction» the UN envisioned would arise from the «unique opportunity» presented by the COVID-19 crisis.

Make no mistake, the UN wants us to accept that the eradication of our ostensible human rights is a way of protecting those same human rights whenever we face potential «harm.»

Ironically, this effort to completely discard the UDHR is entirely consistent with Article 29.2 and Article 29.3 of that very document. This illustrates the complete farce that the UN’s «human rights» actually are.

As we shall discuss in Part 2, there is no end to the list of crises the UN and the overarching G3P might choose to pronounce. Unique opportunities to control our behaviour through a system of «human rights» permits abound.

Access to Information?

The censorship of claimed «misinformation» and «disinformation» is a key part of SDG16. For example, SDG16.10 claims to guarantee «public access to information» and to «protect fundamental freedoms.» Yet, perversely, this same SDG is being used by the UN and other groups to justify online censorship under the guise of addressing «information issues.» The «issue» is any information that challenges or discredits the institutions that the UN’s remaining SDG16 targets aim to strengthen.

For instance, this kind of censorship has been promoted by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), an influential, US-based think tank whose board is chaired by Thomas Pritzker, head honcho of Hyatt Hotels. Pritzker also happens to be named as a central figure in Jeffrey Epstein’s criminal sex trafficking operations; Epstein himself nicknamed Pritzker «Numero Uno.» The President and CEO of the CSIS is John J. Hamre, a former US Deputy Secretary of Defense.

In 2021, the CSIS published an article titled «It’s Time for the United States to Reengage with the SDGs, Starting with SDG16.»

Of SDG16.10 in particular the article says:

A second example of practical alignment would be efforts to bring transparency to instances of misinformation and disinformation, especially around elections and governance. Covid-19 has increased the proliferation of disinformation, misinformation, and censorship in the name of national security and the discrediting of state institutions. SDG16 target 16.10 calls for «ensuring public access to information and protecting fundamental freedoms, in accordance with national legislation and international agreements.» This means SDG16 is uniquely poised to address information issues in relation to both rising authoritarianism led by states and weakening democracy led by malign actors.

In other words, per CSIS, SDG16.10 calls for ensuring public access notto all information but only to approved information that does not «discredit» certain institutions or «weaken» democracy. As we shall see, the UN agrees.

The UN «custodian agency» for SDG16.10—specifically for its «access to information» component—is UNESCO. Sure enough, when we read the 2021 UNESCO report about SDG16.10, we see that «public access to information» means «the presence of an effective system to meet citizens’ rights to seek and receive information, particularly that held by or on behalf of public authorities.»

Other UN documents similarly reveal that the «information» referred to here is information produced by public institutions. Thus, per the UN, «public access to information» refers to a system wherein information produced by governance institutions at the local, national and international levels can be sought and received by the public. It does not guarantee, nor is it meant to guarantee, the free flow of information. Instead, it is meant to ensure a free flow of the information that governments willingly produce for public consumption.

The information that is guaranteed to be publicly accessible by SDG16.10 is the very information that, according to UNESCO and other UN bodies, is meant to foster «trust» in the governance institutions that are to be «strengthened» by other SDG16 targets. This information is also meant to be the «foundation» of building the public perception that these institutions are «transparent» and «accountable.»

The types of information to which SDG16.10 guarantees public access, says UNESCO, include «the way [citizen] data is handled» by governments, federal «budget disclosures» and «health and COVID-19 related information.»

There are many examples of «public authorities» providing «information» that is neither accurate nor verifiable. Indeed, many governments that freely publish such information provide flawed data that is not meant to inform the public but rather to protect «trust» in institutions by obscuring government malfeasance and/or incompetence.

For instance, US Director of National Intelligence James Clapper lied under oath to Congress about how citizens’ data was being utilized by the national security community. But he got away with committing perjury.

Similarly, much of the COVID-19 data «freely» published by governments—the US, the UK and Australia among them—was intentionally manipulated to justify ineffective or counterproductive policies like lockdowns and the global vaccination programme. But those governments, like Clapper, got away with it. There is nothing in SDG16.10 or its target indicators that addresses dishonesty from the institutions that SDG16 seeks to strengthen.

As previously noted, the public’s «trust» in the SDGs is crucial to the UN’s global governance regime (a «regime» we will define shortly). Were the information produced by SDG-implementing institutions (i.e., national governments, the UN, and other UN stakeholder partners) to be outed as faulty and dishonest, the fallout would reduce «trust» in these same institutions. Such a dip, the UN fears, could potentially result in a reduction of citizen «compliance» with UN-approved, SDG-related mandates and edicts.

Thus, with regard to SDG16.10—or any part of any SDG, for that matter—we may conclude that, instead of ensuring that the information to which it guarantees access is accurate, the UN and its stakeholder partners aim to create a regime whereby those who might be able to show that state-produced information is inaccurate are silenced for the sin of reducing «trust» and «weakening democracy.» The silencing enables the UN to claim these people threaten «fundamental freedoms» and «human rights.»

One UN SDG-focused blog noted that «misleading or false information undermines social trust and jeopardises access to reliable information.»

This particular post was referring to COVID-19 vaccinations. It characterized «misleading or false information» as doubts about the vaccines’ safety and efficacy, despite the fact that the data clearly show—then and now—that the vaccines were neither effective nor safe.

The UN’s idea of «reliable information» is UN-approved information that reinforces the preferred narratives of the UN and its strategic “stakeholder partners,” from the WEF to aligned national governments.

Another example that highlights the UN’s views on «reliable information» is the UN’s «Verified» campaign. When it was launched in 2020, UN Secretary-General Guterres had this to say about «misinformation»:

Misinformation spreads online, in messaging apps and person to person. Its creators use savvy production and distribution methods. To counter it, scientists and institutions like the United Nations need to reach people with accurate information they can trust.

Per the UN, the «Verified« campaign saw the UN Department of Global Communications «partner with United Nations agencies and country teams, influencers, civil society, business and media organizations to distribute trusted, accurate content and work with social media platforms to root out hate and harmful assertions about COVID-19.»

Yet, despite the UN’s claim that the information it was distributing was «accurate,» it was provably inaccurate.

For instance, the Verified website insists that COVID-19 vaccines «are saving lives»—a statement solely based on UK government data on COVID deaths before and after the country’s vaccine rollout. It fails to note that UK government data on COVID deaths was intentionally misleading.

In addition, the Verified site continues to claim that the COVID-19 vaccine stops disease transmission, which it does not.

Also, Verified falsely characterizes mass vaccination as the only way to «end the pandemic.» Again, verifiably false.

These falsehoods are set within the UN’s claim that it «owns the science.» Speaking at the WEF’s anti-disinformation panel, UN Under-Secretary-General for Global Communications Melissa Fleming outlined how the UN had partnered with Google and TikTok to rig their respective search results.

We own the science, and we think that the world should know it.

Nothing could be more «anti-scientific» than this statement. Yet the UN continually accuses others of spreading «anti-scientific» disinformation.

The UN insists that, under SDG16.10, the public should be guaranteed access only to the «reliable,» «accurate» information that only it and its stakeholder partners provide. Yet this world body routinely provides inaccurate information when claiming to be doing the opposite.

The UN promotes the need to counter misinformation and disinformation, which it defines, respectively, as the «accidental spread of inaccurate information» and the «intentional spread of inaccurate information.» But, as shown above, this world body is not interested in providing «accurate» information or pointing out «inaccurate» information. Instead, in the context of SDG16.10, it seeks to become a global arbiter of «truth.»

The UN Human Rights Commissioner, Michelle Bachelet, has pushed for increased social media regulation and for the UN and its allies to work directly with Big Tech. All of the world’s «Big Tech» corporations, like the UN itself, are G3P members.

Also, Bachelet uses language that «disses» any information contrary to the UN narrative. She has framed dis- and misinformation as symptoms of «global diseases» that undermine «public trust.»

Yet, stunningly, in the same breath, she (along with other UN officials) asserts that censorship efforts to counter disinformation should not infringe on the freedom of expression and other important «human rights.»

In a preposterous attempt to get around this irreconcilable dichotomy, Bachelet and her UN cronies return to the second part of SDG16.10: «protect fundamental freedoms.» They characterize disinformation and misinformation as being whatever negatively impacts «fundamental freedoms» and «human rights.» Such «harmful» content, they insist, needs to be actively stifled.

Here is one specific example: The UN Secretary-General’s report on countering dis- and misinformation, published last year, was explicitly titled «Countering disinformation for the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms.» It asserted that «countering disinformation» must somehow «promote» and «protect» both «fundamental freedoms» and «human rights.»

In another example, the UN Human Rights Council adopted a resolution which inveighed against «the increasing and far-reaching negative impact on the enjoyment and realization of human rights of the deliberate creation and dissemination of false or manipulated information intended to deceive and mislead audiences, either to cause harm or for personal, political or financial gain.»

This resolution was sponsored by the US and the UK governments, both of which are notorious for spreading propaganda and for pushing for excessive censorship of independent media. The resolution explicitly frames «false information» as information that negatively impacts the «enjoyment and realization of human rights.»

Clearly, the «enjoyment» of «human rights» does not extend to enjoying the alleged human rights of free speech or freedom of expression. Both of these are inalienable rights which cannot be removed or infringed by anyone or any institutions. But, as «human rights,» they can easily be swept aside or redefined.

A third example is the UN’s promotion of what it calls the «ABC» approach to countering inaccurate information. ABC stands for «actors,» «behaviour» and «content,» as this UN document on combating disinformation explains:

Experts have pointed to the need to address the «actors» (those responsible for the content) and the «behaviour» (the manner in which information is disseminated), rather than the «content» as such, in order to effectively counter information operations while protecting free expression.

Thus, the UN intends to target the individuals who produce the alleged «disinformation» or «misinformation» and stop them from disseminating it.

As we shall see, Interpol has been chosen by the UN to implement much of SDG16. Interpol is intimately involved with the UN’s strategic partner, the WEF, in a plan to label those who produce misinformation and disinformation as «cybercriminals.»

Strengthening the Regime

In its 2013 exploration of the Post-2015 Development Agenda (Agenda 2030), the UN said:

Partnership can promote a more effective, coherent, representative and accountable global governance regime, which should ultimately translate into better national and regional governance [and] the realization of human rights and sustainable development[.] [. . .] In a more interdependent world, a more coherent, transparent and representative global governance regime will be critical to achieve sustainable development in all its dimensions. [. . .] A global governance regime, under the auspices of the UN, will have to ensure that the global commons will be preserved for future generations.

The UN calls itself a «global governance regime.» It is arbitrarily assuming the authority to seize control of everything («the global commons»), including humans, both by enforcing its Charter—citing its misnamed «Human Rights» declaration—and by fulfilling its «Sustainable Development» agenda.

Note that the «global governance regime» will ultimately «translate into better national and regional governance.» This means that the role of each national government is merely to «translate» global governance into national policy. Electing one political party or another to undertake the translation makes no material difference. The policy is not set by the governments we elect.

As nation-states one by one implement SDG-based policies, the regime further consolidates its global governance. And since the «global governance regime will be critical to achieve sustainable development,» the two mechanisms—global governance and sustainable development—are symbiotic.

Again, by the UN’s own admission, inalienable rights are the «foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world.» Yet the UN’s entire Charter-based human rights framework comprehensively rejects the principle of inalienable and immutable rights.

The UN Charter is, therefore, an international treaty that establishes a global governance regime which stands firmly against «freedom, justice and peace in the world.» All of the UN’s «sustainable development» projects should be understood in this context.

Unsurprising for a «global governance regime,» the UN has created several targets of SDG16 that deal with creating «strong institutions,» mainly at the level of global governance. For example, SDG16.8 calls for the broadening and strengthening of «the participation of developing countries in the institutions of global governance.»

The SDG16.8 targets are vague. Progress toward them will supposedly be measured by monitoring the «proportion of members and voting rights of developing countries in international organizations.» This is hardly a commitment to afford those developing nations any greater say in decision-making, however.

The definition of «the institutions of global governance» is equally ambiguous. For Harvard scholars, it means a set of global organisations, such the International Criminal Court (ICC), the World Trade Organization (WTO), regional human rights courts, and the United Nations, etc. For students of «global governance» at Bremen University, the «institutions» fit within a decentralised network of different «actors» that provide regulations based upon international norms and rules.

What all these globe-wide organisations have in common is that they exercise supranational authority to some degree.

The WTO influences, coordinates and often sets national governments’ trade policies.

The ICC supposedly has «global» jurisdiction to try the crimes of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and, since 2018, the crime of «international aggression.»

The UN considers itself chief among all supranational organisations. Member nation-states agree to cede their sovereignty to the fifteen-member Security Council and, in particular, to the five permanent members of that Council.

Under its aforementioned Charter, the UN places nearly all executive power in the hands of those five permanent members: the US, the UK, France, Russia and China. Regardless of SDG16.8, the UN is not proposing to amend its own Charter and has shown little interest in living up to the promise of its own SDG targets and indicators.

On the contrary, as we head toward the new multipolar world order, the UN’s permanent Security Council partners—most notably the Russian and Chinese governments—are calling for a «world order» based upon the «purposes and principles» of the UN Charter. In other words, they are avid promoters of a firmer «global governance regime.»

UN General Assembly (GA) delegates, meanwhile, have been requesting reform of the UN Security Council for decades. Namely, they want the Security Council to more broadly represent the nation-states by having more than fifteen members.

The official Russian government position agrees with the GA delegates. Russia seeks to promote «inclusion» by admitting to the Security Council more nations from Africa, South America and Asia.

The Russian Permanent Mission to the UN explained its stance this way:

A just and democratic world order cannot be achieved without a strict observance of the principles of the supremacy of international law, mainly of the UN Charter and the prerogatives of the UN Security Council. [. . .] All the decisions taken and mandates given by the UN Security Council are binding on all Member States. [. . .] The purpose of the reform of the UN Security Council is to achieve broader representation without damaging the effectiveness and efficiency of its work.

Upon closer scrutiny, though, we observe that «broader representation» that does not undermine the «effectiveness» of the Security Council is impossible. Any change intended to empower «developing countries in the institutions of global governance» is instead likely to maintain and consolidate Security Council dominance. The UN Charter is unambiguous on this point.

Under the Charter, the GA is supposedly a decision-making forum of «equal» member states. The Charter then outlines all the reasons why it isn’t.

Article 11 decrees that the GA’s powers are limited to discussing «the general principles of co-operation.» Its decision-making ability is extremely limited.

Article 12 decrees that the GA can deliberate upon any dispute between member states only if the Security Council allows it.

Article 24 ensures, in any practical sense, that the Security Council has sole responsibility for «the maintenance of international peace and security.»

Article 25 compels all other GA member states to follow the orders issued by the Security Council.

Article 27 decrees that at least nine of the fifteen Security Council member states must be in agreement for a Security Council resolution to be enforced. Five of those nine in concurrence must be the permanent members. Each of the five has the power of veto. Thus, simply adding more members to the Security Council won’t change the supremacy of the permanent members in any meaningful sense.

Articles 29 and 30 establish the Security Council as an autonomous decision-making body within the UN power structure. It goes without saying that the GA is allowed to «elect» only the non-permanent members of the Security Council following the recommendations of the Security Council.

Articles 39 through 50 (Chapter VII of the Charter) further empower the Security Council. The Council is charged with investigating and defining all alleged security threats and with recommending procedures and adjustments for the supposed remedy to those threats. The Security Council dictates what further action, such as sanctions or the use of military force, shall be taken against any nation-state it considers to be a problem.

Article 44 notes that, «when the Security Council has decided to use force,» the only consultative obligation it has to the wider GA is to discuss the use of another member state’s armed forces once the Security Council has ordered that nation to fight. For a country that is a GA-«elected» member of the Security Council, practically unlimited use of its armed forces by the Security Council’s Military Staff Committee is a prerequisite for Council membership.

The UN Secretary-General, identified as the «chief administrative officer» in the Charter, oversees the UN Secretariat. The Secretariat runs the UN. It commissions, investigates and produces the reports that allegedly inform UN decision-making.

The Secretariat staff members are appointed by the Secretary-General. Article 97 of the UN Charter determines that the Secretary-General is «appointed by the General Assembly upon the recommendation of the Security Council.»

Under the UN Charter, the Security Council is made king. This arrangement affords the governments of its permanent members—again, China, France, Russia, the UK and the US—considerable additional authority. There is nothing egalitarian about the UN Charter. The UN Charter is the embodiment and essence of centralised global power and authority.

In the highly charged political arena created by the UN Charter, the geopolitical power struggle often seems futile. Here, in no special order, are a few illustrations of that futility—evidence of the permanent members’ clout.

Speaking in January 2023, Russian Federation Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said that the Russian Federation strongly supports expanding the composition of the Security Council. He made no mention of curtailing the permanent members’ additional powers.

Last fall, when ten members of the Security Council attempted to pass a resolution describing the referendums in the former Ukrainian oblasts of Luhansk, Donetsk, Kherson, and Zaporizhzhya as «a threat to international peace and security,» the Russian Federation, as a permanent member of the Security Council, vetoed the resolution. The Russian government is among the permanent members apparently eager to retain its power.

When the Russian government discovered a network of US-funded biological research labs in Ukraine, it and the Chinese government requested a UN commission to investigate the labs. The Western-aligned members of the Security Council blocked the investigation.

In a joint February 2022 statement, the Russian and Chinese governments—referring to themselves as «the sides»—stated:

The sides underline that Russia and China, as world powers and permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, [. . .] strongly advocate the international system with the central coordinating role of the United Nations in international affairs, defend the world order based on international law, including the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations.

As permanent UN Security Council members, neither the Russian nor the Chinese government, despite their apparent unwavering commitment to «sustainable development,» seem to actually wish to see «developing countries» have greater «voting rights» at the UN. Instead, their apparent objective is to consolidate their own elevated positions within the hierarchy established by the UN Charter.

The other three permanent members of the Security Council, equally eager to retain their dominance, take the same stance on the Charter.

US President Joe Biden, for instance, called the Charter the «foundation of a stable international rules-based order.»

France’s President Emanuel Macron said the Charter promises «a modern international order.»

UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak said the UK government would work to «uphold international law and the United Nations Charter.»

Despite current geopolitical tensions, these countries unanimously agree not only on the role of the UN Charter but also on every facet of the UN’s touted «sustainable development.»

— SDG16.8 promises to strengthen the «institutions of global governance.» It does not promise a form of global governance that will benefit humanity.

— Even though the UN remains a blatantly political organisation riven with internecine conflicts, the supposed hostility between East and West does not extend to re-imagining the «global governance regime.» There is, instead, unanimous agreement to strengthen it.

— In terms of G3P-forwarded sustainable development, national governments are enabling public partners to advance their own interests by implementing the UN’s politically motivated SDG policies and by exploiting the politically driven UN Charter. There is no evidence, from any quarter, that any national government values the humanitarian principles that either the SDGs or the UN Charter purportedly embody.

From Global Governance to a Global Police State: Interpol’s Global Policing Goals

Placed after SDG16.10, SDG16.a calls for strengthening «relevant national institutions, including through international cooperation, for building capacity at all levels» with the goal of preventing «violence» and for combating «terrorism and crime.»

In 2018, the UN identified Interpol as the law enforcement organisation that was «uniquely positioned to be the implementing partner of a number of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).»

This designation as «implementing partner» of the SDGs led Interpol to develop its Seven Global Policing Goals, which, it says, are «aligned with the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. [. . .] This applies especially to Goal 16 [SDG16].»

Interpol outlines what it hopes to achieve with its «sustainable» law enforcement:

As the only police organization that works at the global level, Interpol plays a unique role in supporting international policing efforts. To do this in a consistent manner across the world, it is important that all actors in the global security architecture share an understanding of the threats and work towards the same outcomes. [. . .] Global Policing Goals focus the collective efforts of the international law enforcement community to create a safer and more sustainable world for future generations.

Many of Interpol’s Global Policing Goals necessitate the type of surveillance that can most easily be enabled by introducing digital IDs and CBDCs (a topic that will be discussed in detail in Part 2). For instance, most of the seven goals share a sub-goal that refers to the need to «trace and disrupt financial streams» and, elsewhere, the need to «identify and disrupt illicit financial streams» of «criminals» and «terrorists.»

Global Policing Goal 6, for example, focuses on curbing «illicit markets» and contains these sub-goals: «build mechanisms to detect emerging illicit markets» and «strengthen capacity to investigate and prevent illicit trade.»

This kind of work obviously calls for tools that can conduct mass financial surveillance. In order to preside over such operations, Interpol must first obtain the authority to access a system of mass financial surveillance.

Conveniently, the required global surveillance of commercial activity and money flows—to be explored Part 2—can be achieved through the realization of SDG16.9’s digital ID paradigm, whereby biometric digital ID is a prerequisite for participation in the economy. This idea is explicitly promoted by the UN paper «The People’s Money: Harnessing Digitalization to Finance a Sustainable Future.»

However, it is not just mass financial surveillance that Interpol seeks. A sub-goal of its Global Policing Goal 2 («promote border integrity worldwide») is to «identify criminal and victim movements and travel.»

To fulfil that goal, tools for mass geolocation surveillance of the world’s population would be needed. How handy that Interpol’s I-Checkit programme is designed to both achieve this ambition and centralise control of and access to the global population surveillance system.

Specifically, the I-Checkit programme pushes for countries to «heighten» their «identity management measures.» It also urges airlines, the maritime industry and banks to collaborate in real-time with law enforcement to decide whether or not a person should be allowed to travel.

Though Interpol’s Goal 2 is being billed as a means of stopping «organized crime,» it is more likely meant to further the UN’s ambitious digital ID agenda. As we witnessed when digital vaccine passports were introduced during the faux pandemic, the rollout and enforcement of biometric digital ID presents a tangible threat to everyone’s freedom of movement and civil liberties.

Unsurprisingly, Interpol has already teamed up with a variety of biometric digital ID companies, two of which (Idemia and Onfido, to be precise) played a major role in facilitating vaccine passports during COVID-19 and more recently have been creating «digital driver’s licenses» (that is, biometric digital IDs) for several US states.

Goal 4 of Interpol’s SDG-related Global Policing Goals is to «secure cyberspace.» One of its related sub-goals is to «establish partnerships to secure cyberspace.» The chief partnership that Interpol has joined in service of fulfilling this goal is the WEF’s Partnership Against Cybercrime (WEF-PAC).

A few facts about WEF-PAC:

(1) Its members, like Interpol, aim to «secure cyberspace.» They are mainly law enforcement agencies from the US, UK and Israel, but they also include some of the world’s largest commercial banks and fintech companies.

(2) It has been advocating the creation of a global fin-cyber entity to regulate the internet, with the ultimate goals of ending financial privacy and preventing anonymity under the guise of combating «cybercrime.»

(3) It is run by Tal Goldstein, a career Israeli intelligence operative who designed an intelligence policy that transformed Israel’s private cybersecurity industry into a cut-out for that country’s intelligence operations.

WEF-PAC argues for its purpose by pointing out:

[I]n order to reduce the global impact of cybercrime and to systematically restrain cybercriminals, cybercrime must be confronted at its source by raising the cost of conducting cybercrimes, cutting the activities’ profitability and deterring criminals by increasing the direct risk they face.

To achieve these goals, WEF-PAC envisions «harnessing the private sector to work side by side with law enforcement officials.» This is a typical G3P move—and one that sounds similar to the model Interpol follows with its I-Checkit programme.

Shockingly, WEF-PAC calls for public-private «cooperation» even if it’s «not always aligned with existing legislative and operational frameworks.» In other words, cooperation should be permitted even if it is illegal.

Granted, most of WEF-PAC’s materials refer to cybercriminals as those who engage in hacks or ransomware attacks and other truly criminal activities. Yet in one place it broadens the definition of «cybercriminals» to include those who use technology to «uphold terrorism» and «spread disinformation to destabilize governments and democracies.»

Thus, we see a several-pronged attack on the so-called spreaders of «disinformation»: They will not only be made out as criminals by the implementation of SDG16.10 and by the ABC crackdown, they will also be subject to Interpol’s SDG16-linked Global Policing Goal of «securing cyberspace» and to WEF-PAC’s pursuit of government-destabilizers.

From multiple angles, then, SDG16 and its implementing partners are seeking to construct a surveillance paradigm where dissenters’ speech and financial transactions are closely monitored, criminalized, and targeted. The «strong institutions,» strengthened even further by SDG16, will be used to keep societies «peaceful»—i.e., free of the «crime» of resisting tyranny—through mass surveillance of the internet and of all commercial activity as well as the mandatory use of digital IDs.

«Pay-to-Play» Justice Systems

The current president of Interpol is the General Inspector of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) Interior Ministry, Maj Gen Ahmed Naser Al-Raisi. Worryingly, he has been accused of overseeing the torture of citizens from the UK, Qatar, Turkey, the UAE, and elsewhere.

Despite the UK government’s close political and commercial relationship with the UAE, prior to Al-Raisi’s «election» as Interpol President, former Director of Public Prosecutions for England and Wales Sir David Calvert-Smith published a report concerning Al-Raisi and the UAE’s influence upon Interpol’s opaque internal election processes.

The report noted:

The President [of Interpol] sits at the top of the entire Interpol structure and commands considerable power and authority. [. . .] [T]he mechanism for the election of the President is far from transparent. Interpol has declined repeated requests by rights organisations to demystify the presidential election process. [. . .] Interpol is not a transparent organisation.

Aside: Interpol’s lack of transparency is, of course, at odds with the UN Post-2015 Development Agenda’s declared commitment to foster a «transparent and representative global governance regime.»

Turning its attention to Al-Raisi, the report added:

Since Al-Raisi’s appointment as General Inspector of the Ministry of Interior of the UAE in 2015, there have been [. . .] numerous allegations of torture and abuse in Emirati jails, both in Abu Dhabi as well as in Dubai’s prisons and jails. [. . .] Major General Al-Raisi is unsuitable for the role. [. . .] He has overseen an increased crackdown on dissent, continued torture, and abuses in its criminal justice system. [. . .] He is a far from ideal candidate for leadership of one of the world’s most important policing organisations.

Whether the allegations cited in Calvert-Smith’s report had been proven or not, given the controversy, it seems remarkable that Interpol proceeded to appoint Al-Raisi.

But perhaps we shouldn’t be shocked. After all, this isn’t the first time that Interpol, the UN regime’s «implementing partner» for sustainable, global law enforcement, has been headed by questionable characters.

In 2008, Interpol’s then-President Jack Selebi resigned after he was charged with bribery. Selebi was subsequently sentenced to 15 years in a South African prison for taking bribes from international drug traffickers in return for protecting them from investigation.

In 2018, China’s Vice Minister of Public Security, Meng Hongwei, vanished from his post as Interpol President and resigned soon thereafter. In 2020, he was sentenced in China to more than 13 years’ imprisonment for accepting an estimated $2 million (USD) in bribes.

Digging deeper, we find that Interpol’s alleged history of being led by criminals and torturers is only the most visible part of its corruption.

Interpol has been given the authority to issue international arrest warrants, often referred to as «Red Notices.» Similar to international extradition requests, they notify national law enforcement agencies that one of Interpol’s 194 member states has issued a warrant and is seeking the named person(s). Red Notice recipient states apply different jurisdictional interpretations. Some consider them active warrants, others merely advisory or alert notices.

The Calvert-Smith report found that abuse of Red Notices by authoritarian regimes seeking to detain political dissidents or opponents was commonplace:

In blunt terms, there is strong evidence that despotic states issue Interpol Red Notices in order to arrest and extradite political opponents and business-people whose interests do not align with the regime. [. . .] The UAE is notorious for its abuse of Interpol — many of their requests have been removed. [. . .] The UAE has a poor human rights record[,] meaning that extradition to the UAE exposes individuals to the risk of torture and mistreatment[,] and political changes have meant that a person can become an «enemy of the state» overnight.

Why has abuse of Red Notices seemingly passed through the Interpol system «undetected»? Looking at the financial «support» UAE gave to Interpol prior to Al-Raisi’s eyebrow-raising elevation to President, the Calvert-Smith report observed:

The Interpol Foundation for a Safer World was set up in 2013 and is a not-for-profit organisation[.] [. . .] Its sole purpose is to [financially] support Interpol. [. . .] It seems that the foundation is in fact totally reliant on the UAE. [. . .] It is difficult to escape the conclusion that the Interpol Foundation for a Safer World’s sole purpose is to be a channel by which to funnel cash from the UAE government into Interpol.

Interpol also happily accepts money from NGOs, philanthropic foundations, governments and private corporations—all the while insisting it is apolitical and incorruptible.

Following a 2015 investigation of Interpol, journalist Jake Wallace Simons reported:

Interpol has signed deals with a large number of private «partners,» including tobacco giants, pharmaceutical firms and tech companies — such as Philip Morris International, Sanofi, and Kaspersky Lab — the proceeds of which have swollen its operational budget by almost a third.

In other words, Interpol’s «international policing efforts» can be bought, if you can afford them. Its deal with Philip Morris International (PMI), for example, effectively compelled Interpol to promote PMI’s «Codentify» tobacco package marker system to its member states. The alleged purpose of Codentify was to tackle the international counterfeit and illicit tobacco trade.

The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC), adopted in 2003, established a protocol for tobacco track and trace systems. It viewed its work as central to efforts to tackle the illicit and counterfeit tobacco trade. However, only 7% of that total trade consisted of counterfeit products. The vast bulk of tobacco smuggling was comprised of the illegal distribution and sale of authentic tobacco industry products.

Therefore, the idea that a global tobacco corporation (PMI) should use its own track and trace system (Codentify) in partnership with a global law enforcement agency (Interpol) to «seize» illicit tobacco looked more like an attempt to control the illegal tobacco trade rather than end it.

The head of the FCTC Secretariat, Vera da Costa e Silva, observed:

Both the FCTC and its Protocol are crystal clear that the tobacco industry is part of the problem, not part of the solution.

Yet, despite Interpol’s suspect track record, the UN would have us believe that Interpol is the ideal «implementing partner» for a number of SDGs, most specifically SDG16.

Hardly. Considering how Interpol defines the threats that will be policed by the «global security architecture» under the auspices of the «global governance regime,» there is no reason to be confident that it will help prevent «violence» or reduce «terrorism and crime.»

There are no grounds to believe that Interpol is capable of delivering its 5th Global Policing Goal to «promote global integrity» by proclaiming «good governance and the rule of law» and «a culture of integrity where corruption is not acceptable.»

Nor do we have much cause to hope that SDG16 related “laws” will be equitably enforced by the UN’s affiliate, the International Criminal Court (ICC).

First, some history:

In 1993, the UN created the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY). The ICTY eventually convicted Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadžić in 2016 and Bosnian Serb military commander Ratko Mladić in 2017 for genocide and crimes against humanity.

In 1994, the UN set up the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. And in 2002, in cooperation with the government of Sierra Leone, it established the Special Court for Sierra Leone to investigate the atrocities inflicted during the country’s civil war (1991–2002).

Combined, these initiatives provided impetus for the UN to create the world’s first permanent international centre of justice: the International Criminal Court (ICC).

The original motivation for the creation of the ICC, however, is said to have come from the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ). (More on the ICJ later.) The ICJ took credit as one of the main stakeholders driving the 1998 ratification of the Rome Statute, which laid the legal foundations for the subsequent ICC.

The ICC is purportedly independent, although it functions within the parameters set by its «mutually beneficial» Relationship Agreement with the UN.

Article 3 of the ICC-UN agreement states:

The United Nations and the Court agree that, [. . .] they shall cooperate closely, whenever appropriate, with each other and consult each other on matters of mutual interest pursuant to the provisions of the present Agreement and in conformity with the respective provisions of the Charter and the Statute.

Considering that the UN is overtly political organisation, the ICC’s close cooperation with that intergovernmental body suggests that the ICC, too, could be politically biased.

The evidence provides good reason to suspect that’s the case:

— The US, Russian and Chinese government are not signatories to the Rome Statute and don’t recognise its jurisdiction, but, by virtue of Article 13(b) of the Statute, their status as permanent members of the Security Council allows them to make referrals to the ICC prosecutor. Consequently, the ICC could be used by them for politically motivated prosecutions.

— In March 2023 the ICC issued an international arrest warrant for Russian President Vladimir Putin and the Russian Commissioner for Children’s Rights, Maria Lvova-Belova. The charges: the war crimes of unlawful deportation of population (children) and of unlawful transfer of populations (children) from occupied areas of Ukraine to the Russian Federation.

The Western mainstream media (MSM) alleges that up to 16,000 children were «illegally deported.» Roman Kashayev, a member of the Russian Permanent Mission to the UN, reported that approximately 730,000 children were relocated deeper within Russian borders from, what are now, the Russian oblasts of Luhansk, Donetsk, Kherson, and Zaporizhzhya. The relocation would seem a sensible precaution in light of the Ukrainian military’s continual shelling of civilian areas in the targeted oblasts.

The Russian Federation government admits that some of these children travelled without their parents, whose whereabouts, it claims, are unknown. It is of course possible that some illegal activity has taken place amidst the evacuation. But there are also reasons to suspect that the ICC warrants were issued as a result of political pressure.

The ICC Chief Prosecutor who submitted the warrant request is UK lawyer and King’s Council Karim Khan KC, who works out of the prestigious Temple Chambers in London. He submitted the warrant application on the 22nd February 2023. The ICC formally issued the warrant on the 17th March 2023.

On the 3rd March 2023, two weeks after he submitted the application, Khan delivered a speech to the United4Justice conference in Lviv, Ukraine, during which he said:

I’ve been with the Prosecutor General [of Ukraine.] [. . .] The men and women of my office have been to so many locations [with the Ukrainian Prosecutor General’s office.] [. . .] Unfortunately, Ukraine is a crime scene. [. . .] We’ve received [allegations] that children how been deported outside Ukraine, into the territory of the Russian Federation. [. . .] Our yardstick is evidence. It is to look at and investigate affirmatively incriminating and exculpatory evidence equally. But we have this commitment.

Khan’s remarks suggest that he submitted the warrant request based upon «received» allegations alone. While the commitment to «look» for evidence is quite normal, it is perhaps unusual to accuse a major world leader and his staff of effective child trafficking and war crimes without any apparent evidence. Again, political motivation seems likely.

The United4Justice campaign is a Western-backed political operation working in Ukraine. It claims its intention is to construct a «web of accountability for international crimes.» A look at the United4Justice initiatives, however, reveals some questionable sponsors—among them, USAID, a known CIA front organisation; Pravo-Justice, an EU-backed programme focused on aligning Ukrainian law with the EU legal system; and the International Renaissance Foundation (IRF), a Soros-funded Ukrainian NGO that, like Pravo-Justice, seeks legal reform in Ukraine. In short, the political agenda of these organisations and of the United4Justice campaign they support is resoundingly anti-Russian.

Moreover, the United4Justice conference that Khan addressed was organised by Ukrainian authorities and the EU Agency for Criminal Justice Cooperation (Eurojust). They are keen to see the Russian Federation prosecuted for the new international crime of «aggression.»

To this end, Eurojust has established the International Centre for Prosecution of the Crime of Aggression against Ukraine (ICPA). According to Eurojust, the Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (Khan’s office) «may take part in the cooperation via the ICPA when certain conditions are met.»

On 20 March 2023, three days after the ICC issued the warrant, the UK government convened an international meeting—hosted by the UK Deputy Prime Minister Dominic Raab—at which it announced a boost in UK funding for the ICC, doubling its previous contribution. The purpose of the funding, said the UK government, was to ensure that «more UK experts,» like Karim Khan, worked for the ICC. Khan delivered one of the opening speeches.

There is no discernible difference between the UK government funding the ICC and the UAE government funding Interpol. The objective in each case is to garner influence.

The only logical conclusion one can reach is that, far from being «unbiased» international institutions suitable for delivering the UN’s SDGs, both Interpol and the ICC appear to adopt the biases of the highest bidder by engaging in «pay-to-play» schemes.

We aren’t the only ones to draw this conclusion.

Earlier this year, for instance, academic researchers from the University of Arkansas and the London School of Economics published their findings on the influence of funding upon the ICC. They noted:

The patterns of funding seen at the ICC support the claim that the Court remains, to a significant extent, a tool of powerful states.

Serbian lawyer Goran Petronijevic, a legal adviser to the ICTY, agrees with this assessment. Recently he called Khan’s ICC warrant «a political act. It is not a legal act. It is a provocation against Russia.»

Indeed, the ICC has been mired in controversy since its inception. When the investigative journalists of the European Investigative Collaborations (EIC) network looked into the activities of Khan’s predecessor, ICC Chief Prosecutor Luis Moreno Ocampo, they determined that his actions had «tainted and discredited» the ICC.

Ocampo had served as Chief Prosecutor of the ICC for nearly a decade. It is evident that he held numerous offshore accounts during his tenure. His involvement in the murky business dealings of Libyan tycoon Hassan Tatanaki, not to mention ICC officials’ continuing assistance to Tatanaki after Ocampo’s departure, raise further concerns about ICC integrity.

In sum, to believe that the ICC and Interpol are suitable organisations to promote «the rule of law» requires considerable credulity. Yet, in pursuit of SDG16, suitability is precisely what the UN regime and its partners assert.

SDG16.2: Dangerous UN Hypocrisy

SDG16 promises to eradicate many of the worst crimes in today’s world, including crimes committed against children. For instance, the aim of SDG16.2 is:

End abuse, exploitation, trafficking and all forms of violence against and torture of children.

Yet, contrary to all evidence, ethics, common sense and criminal law, it seems that several important UN partners and «stakeholders» don’t consider paedophilia to be a form of child abuse.

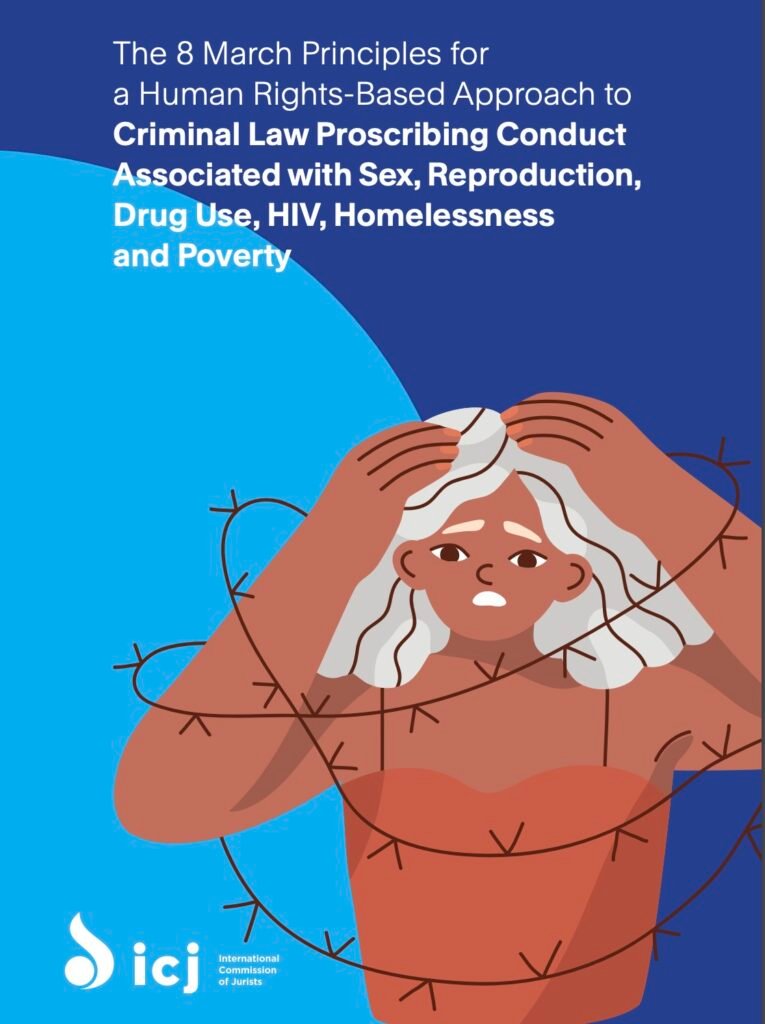

The International Commission of Jurists (ICJ), which was instrumental in the formation of the ICC, is a non-governmental organisation (NGO) that has long been a close «partner» of the UN. The UN and the ICJ have collaborated on numerous joint projects, such as spreading SDG messaging among academic institutions.

The ICJ is an influential UN stakeholder. In 1993, the UN gave the ICJ its Human Rights award for the following reasons:

The International Commission of Jurists was established to uphold the rule of law and the legal protection of human rights throughout the world. It has actively contributed to the elaboration of international and regional standards and has helped to secure their adoption and implementation by governments. The Commission has closely collaborated with the United Nations and actively works at the regional level to strengthen human rights institutions.

The ICJ convened in 1952 as an overtly geopolitical organisation. Its stated purpose was to denounce «human rights abuses,» but only in the Soviet Union. It subsequently broadened its remit and started looking at abuses elsewhere.

In March of this year, The ICJ published its «8 March Principles.» Its alleged objective was «to offer a clear, accessible and workable legal framework — as well as practical legal guidance — on applying the criminal law to conduct.»

In «8 March Principles,» the ICJ advocates:

With respect to the enforcement of criminal law, any prescribed minimum age of consent to sex must be applied in a non-discriminatory manner. Enforcement may not be linked to the sex/gender of participants or age of consent to marriage. Moreover, sexual conduct involving persons below the domestically prescribed minimum age of consent to sex may be consensual in fact, if not in law. In this context, the enforcement of criminal law should reflect the rights and capacity of persons under 18 years of age to make decisions about engaging in consensual sexual conduct and their right to be heard in matters concerning them.

This language opens up the distinct possibility that predatory paedophiles, should they ever be charged, may be able to offer mitigation if they or their lawyers can convince their child targets to testify that they gave their consent.

As we know, coercion is a common paedophile practice. Many child protection organisations—the UK-based National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) among them—recognise that coercion is part of the grooming process:

Grooming is a process that involves the offender building a relationship with a child, and sometimes with their wider family, gaining their trust and a position of power over the child, in preparation for abuse.

Following publication of «8 March Principles,» the ICJ responded to criticism by presenting some straw man arguments.

First, the ICJ said it did not «call for the decriminalization of sex with children.»

Second, the ICJ said it did not suggest «the abolition of a domestically prescribed minimum age of consent to sex.»

Third, the ICJ explained that it was simply offering clear legal guidance to «parliamentarians, judges, prosecutors and advocates.»

True, quite clearly the ICJ did not advocate decriminalising paedophilia.

True, quite clearly the ICJ did not advocate the abolition of the age of consent.

But . . . the ICJ did, quite clearly, introduce the notion, in law, that a child has the «human right» to consent to being raped by an adult.

It is far from clear how lawmakers should interpret this «legal framework and practical legal guidance.»

It is abundantly clear, however, that the ICJ has introduced legal ambiguity where there should be absolutely no legal ambiguity at all.

Sad to say, we should not be surprised by the «8 March Principles.» The UN regime and its multistakeholder partners have an appalling track record of not protecting children.

The WHO regional office for Europe—a UN specialist agency—and the German Federal Centre for Health Education (BZgA) jointly published in 2010 (and updated in 2016) guidelines for schools, titled «Standards for Sexuality Education in Europe.» The authors call their guidance «a framework for policy makers, educational and health authorities and specialists.»

The WHO agreed with Bzga that educators should provide, to infants aged 0-to-4, information about «enjoyment and pleasure when touching one’s own body» as well as information about «early childhood masturbation.»

The WHO says this information should be set within the context that «enjoyment of physical closeness» is «normal.» Even infants, the WHO says, should be taught that «physical closeness as an expression of love and affection.»

According to the WHO, children aged 4-to-6 years should learn to identify potential abusers. It then outlines the advice educators should provide to children in this age range—advice that, the WHO claims, will potentially enable 4- and 5- and 6-year-olds to identify possible risks:

There are some people who are not good; they pretend to be kind, but might be violent.

Of course, all sexual abuse of children is an appalling act of violence, but children may not immediately perceive it as such until well after the act has been committed. Survivors of abuse don’t tend to come to terms with the horrendous psychological and often physical damage inflicted upon them until later in life.

Thus, teaching infants about «sexual pleasure» and telling them that «physical closeness is normal» and «an expression of love,» while simultaneously teaching them that sexual abuse only manifests as «violence,» would appear to place young children at even greater risk of grooming and paedophilia. Such «education» disarms, rather than forewarns, the child.

As for 9-to-12-year-old children, the WHO and the BzgA recommend that they develop the skills to «take responsibility in relation to safe and pleasant sexual experiences for oneself and others.» The WHO believes these children should be able to «make a conscious decision to have sexual experiences or not.»

The WHO is a UN agency and the ICJ is an influential UN «partner.» Contrary to their humanitarian pretensions, the WHO-led «educational guidance,» combined with the ICJ’s legal framework, serves the interests of paedophiles and endangers the lives of children.

Something Is Very Wrong

We will examine SDG 16.9 and expand our exploration of the «interoperable» digital ID network established by the ID2020 Alliance (global public-private partnership) in Part 2. For now, let’s just consider the publicly stated ambition of ID2020:

By 2030, provide legal identity for all, including birth registration.

In its pursuit of SDG16.9, ID2020 set up a partnership between the International Rescue Committee (IRC) and iRespond. The purpose of the partnership was to roll out biometric ID for newborns in the Karen refugee population along the Myanmar-Thailand border.

Heavily promoted by the West’s MSM, the project tied the Karen refugees’ access to food aid and other vital services to their participation in this digital ID system.

Importantly, partners IRC and iRespond said participation in the project was voluntary. But in the same breath, they made it clear that the refugees’ «vaccine status» would be incorporated into their digital IDs.

For the Karen people, access to food and health care hinged upon them presenting approved biometric ID. Registering for the ID was dependent upon their vaccine «status.» Thus, the Karen people were forced to accept vaccination and use digital ID or face starvation and disease without access to medical treatment.

Suffice it to say, there was no IRC or iRespond commitment to freedom, justice and peace. Instead, this UN partner-led project comprehensively ignored the rights of the Karen people.

The ID2020 Alliance’s decision to allow the IRC anywhere near refugee families—the most vulnerable population of all—was injudicious, to say the least. The IRC was one of fifteen «international aid organisations» embroiled in the sex–for–food scandal.

When the scandal came to light in 2000, the UN commissioned an investigation into the activities of its affiliated private aid «partners» and its own aid agencies. The subsequent report found evidence that workers from 40 local and international charities—the latter included the IRC—were in «sexually exploitative relationships with children.» Bluntly put, UN «stakeholder partner» organisations, including the IRC, were infested with child rapists.

The report clearly identified the widespread practice of providing food in exchange for sex—including paedophilia—in refugee camps. Yet the UN suppressed the report for more than sixteen years.

The UN has been equally slow to investigate the wealth of evidence implicating its own peacekeepers in child rape and trafficking operations in 23 countries, notably Haiti and Sri Lanka, as revealed in an April 2017 Associated Press exposé and follow-up.

As if the Haitian children hadn’t already been tortured enough by the UN «peacekeepers,» their victimization wasn’t over. After the January 2010 earthquake, known child trafficker Laura Silsby was caught for the second time attempting to traffic Haitian children. The children she snatched were supposed to be under the protection of the UN. Silsby claimed they were destined for an orphanage in the Dominican Republic, but there was no record of her making any of the required transit applications to Dominican authorities.

In May 2009, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon had appointed Bill Clinton special envoy to Haiti, the poorest nation in the Western Hemisphere. Post-earthquake, Clinton was the obvious choice to be the UN’s international coordinator for Haitian relief efforts. He was thus perfectly positioned to pressure Haitian authorities on Silsby’s behalf, after which she walked free. The evidence strongly suggests that Silsby (now Laura Gayler) was part of larger child trafficking operation involving her originally retained lawyer, Jorge Puello, and his wife.

Interesting that the ICC, which saw fit to issue an arrest warrant to President Putin for child trafficking in Ukraine, has not charged former US President Clinton in connection with child trafficking in Haiti.

Perhaps that «oversight» is due to the Clinton Foundation being so deeply embedded in the global governance regime’s public-private structure?

In 2016, the Clinton Global Initiative, which has been credited with directing philanthropy toward sustainable development, hosted an event to garner support for the UN Trust Fund (UNTF), whose stated mission is to end violence against women and girls. Unbelievably, that same year, it was first reported that defence lawyers for paedophile sex trafficker and intelligence asset Jeffrey Epstein had written that their client was a key part of the small group that had «conceived the Clinton Global Initiative.»

According to the UN, the purpose of the UNTF gathering was to «announce a series of Commitments to Action aiming to advance the gender equality targets of the UN Sustainable Development Goals.» Apparently, this aim is to be achieved through «partnership» with known facilitators of child trafficking.

We might wonder why anyone would «trust» the UN «global governance regime» to «[e]nd abuse, exploitation, trafficking and all forms of violence against and torture of children»—when its specialist agencies and stakeholders and special envoy, plus its peacekeepers and partners, have been caught on innumerable occasions either committing or sanctioning these very crimes.

It is not unreasonable to say that the UN and its agencies and «partners» present a significant risk to children. Clearly—clearly—there is something very wrong at the heart of this dangerous regime.

Peace and Justice for Whom?

The UN is a corrupt «global governance regime.» It continues to deceive the global population about the acres of separation between so-called «human rights» and our real «inalienable rights,» which it studiously ignores and wilfully subverts.

Nation-states compete for influence within the orbit of the UN regime. The governments of those nation-states are part of the vast network, formed by the regime and its various public and private «partners,» that is attempting to implement SDG16.

Most of the SDG16 targets are intended to «reform» sovereign systems of justice and law enforcement and decision-making processes for the benefit of the regime.

SDG16 represents an obvious attempt to consolidate power in the hands of the regime at the expense of national sovereignty and human freedom. This is a matter of extreme concern for many reasons, perhaps most notably because our children must be safeguarded. As things stand, the regime appears to present a clear threat to children across the world.