In Part 1 of our investigation into the United Nations’ (UN’s) Sustainable Development Goal 16 (SDG16) we revealed how the UN proclaims itself a “global governance regime.” We investigated the UN’s exploitation of so-called “human rights” as an authoritarian system of behavioural control permits, as opposed to any form of recognisable “rights.”

We examined how the UN uses what is calls the «policy tool» of human rights to place citizens (us) at the centre of international crises. This enables the UN and its «stakeholder partners» to seize crises as «opportunities» to limit and control our behaviour. The global public-private partnership (G3P), with the UN at its heart, redefines and even discards our supposed «human rights» entirely, claiming «crisis» as justification.

The overall objective of SDG16 is to strengthen the UN regime. The UN acknowledges that SDG16.9 is the most crucial of all its goals. It is, the regime claims, essential for the attainment of numerous other SDGs.

At first, SDG16.9 seems relatively innocuous:

By 2030, provide legal identity for all, including birth registration

But, as ever, when it comes to UN sustainable development, all is not as it initially appears.

SDG16.9 is designed to introduce a centrally controlled, global system of digital identification (digital ID). In combination with other global systems, such as interoperable Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs), this can then be used to monitor our whereabouts, limit our freedom of movement and control our access to money, goods and services.

Universal adoption of SDG16.9 digital ID will enable the G3P global governance regime’s to establish a worldwide system of reward and punishment. If we accept the planned model of digital ID, it will ultimately enslave us in the name of sustainable development.

Digital ID As A Human Right

As we previously discussed, The UN underwent a «quiet revolution» in the 1990s. In 1998, then UN Secretary General Kofi Annan stated that «the business of the United Nations involves the businesses of the world.»

Government’s reduced role was to create the regulatory «enabling environment» for private investors, alongside taxpayers, to finance what would become SDGs. Using the highly questionable «climate crisis» as an alleged justification, in 2015, the UN’s Millennium Development Goals gave way to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

On the 25th September 2015, UN General Assembly Resolution 70.1 (A/Res/70.1) formally established the SDGs by adopting the binding resolution to work towards «Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.»

As soon as the ink was dry on the resolution, the UN set about creating the enabling environment to encourage public-private partnerships to develop a system of global, digital ID. In May 2016, in response to SDG16.9, the United Nations Office for Partnerships convened the «ID2020 Summit – Harnessing Digital Identity for the Global Community.» This established the ID2020 Alliance.

The ID2020 Alliance is a global public-private partnership that has been setting the future course of digital identity since its founding. The global accountancy and corporate branding giant PwC was selected by the UN as the “lead sponsor” of the inaugural ID2020 summit in 2016. Excited about the opportunities digital ID would present, PwC described the ID2020 sustainable development objective:

[. . . .] to create technology-driven public-private partnerships to achieve the United Nations 2030 Sustainable Development Goal of providing legal identity for everyone on the planet. [. . .] Specifically, ID2020’s mission aligns with development target 16.9, “Legal identity for all, including birth registration”. Thirty percent of the world’s population, approximately 1.5 billion people, lack a legal identity, leaving them vulnerable to legal, political, social and economic exclusion.

Offering us digital ID to address so-called “economic exclusion,”—more on this shortly—the ID2020 Alliance duly launched in 2017 and set its Agenda2030 goal:

Enabling access to digital identity for every person on the planet.

You will note that the UN’s SDG16.9 makes no mention of global “digital ID.” Sustainable development, as it is presented to us, is nothing if not deceptive.

The ID2020 Alliance announced a «strategic, global initiative» for digital ID that presented humanity with a quite astonishing idea. The regime stated that the lack of «legal identity»—digital ID—prevented people from accessing «healthcare, schools, shelter, justice, and other government services,» thereby allegedly creating what it called «the identity gap.»

Empowered by the «global governance regime,» the ID2020 Alliance expanded on the idea that we are only permitted to live in «its» society if we can prove who we are, using its digital ID, to the satisfaction of the G3P regime.

The ID2020 manifesto states:

The ability to prove one’s identity is a fundamental and universal human right. [. . .] We live in a digital era. Individuals need a trusted, verifiable way to prove who they are, both in the physical world and online. [. . .] ID2020 Alliance partners jointly define functional requirements, influencing the course of technical innovation and providing a route to technical interoperability, and therefore trust and recognition.

SDG16.9 “sustainable development” means we must use digital ID that meets the functional requirements of the ID2020 Alliance partnership. Otherwise we will not be protected in law, service access will be denied, our right to transact in the modern economy will be removed, we will be barred from participating as «citizens» and excluded from so-called «democracy.»

This past August, ID2020 joined with the Digital Impact Alliance (DIA) to “push for digital transformation.” That said, ID2020 “joining” DIA is a bit of a misnomer, considering that both of these public-private partnerships are essentially run by the same organisations.

Speaking about the launch of its “partnership” with DIA, ID2020 founder John Edge, said:

[W]e established ID2020 to be a time-bound exploration of alternative systems for individuals to prove they exist.

In accordance with SDG16.9 “transformation,” if you don’t have the properly authorised digital ID then, as far as the regime is concerned, you don’t exist. As DIA explains, everyone must have “the trusted digital tools they need to fully participate in society.” If you don’t submit, you are literally nobody and thereby excluded from “society.”

The DIA calls its methodology “do[ing] digital right.” Its backers, such as the UN, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, USAID (widely believed to be a front for the CIA) and the UK and Norwegian governments, are all behind the DIA mission:

We use our expertise to influence the influential, encouraging the world’s largest investors and most effective policymakers to “do digital right”, emphasizing the importance of design, implementation, and governance.

Establishing global governance “with teeth” is the primary objective of the G3P regime, and “sustainable development” is its chosen mechanism to achieve its ambitions. As a regime partner, the DIA has been entrusted as the steward of the regime’s associated Principles for Digital Development.

Among these “principles” is the commitment to harvest as much human data as possible and to provide “the right people” with access to that data:

When an initiative is data driven, quality information is available to the right people when they need it, and they are using those data to take action.

The “world’s largest investors” are particularly encouraged to use their money tackle the alleged “identity gap” in least developed countries (LDCs) first. This will be achieved by prioritising investment in “cross-sectoral digital public goods and architecture.”

Very graciously, the G3P will “allow LDCs to be the stewards of their national digital agendas”—providing, of course, that they fully comply with the right “agenda.”

Given the cross-cutting nature of digital and its role in reaching all of the SDG targets, we believe that the current moment in time is ideally suited for such a “push” in LDCs.

The objective is to marshal “the necessary resources to fund and achieve national and global targets.” That is to say, LDC national governments are “allowed” to adopt “digital transformation” policies aligned to “global targets.”

There is no doubt that the ID2020 Alliance fully appreciates the implications of what it is doing. In a now quite infamous 2018 article, one of the founding partners of ID2020, Microsoft, published the following:

As more and more transactions become digital in nature and are built around a single global identification standard, supported by Microsoft, the question of who will govern this evolving global community and economy becomes relevant. Especially since non-participants in this system would be unable to buy or sell goods or services.

While the regime talks about «inclusion,» it is building a global digital ID system that is inherently exclusionary and can punish regime critics or silence dissident voices by cutting them off from its «society.» Being forced to use digital ID against your will is not a “right,” but it can be called a «human right» because, as defined by the UN, those are not rights, they are policy tools.

A global system of biometric digital ID can only become «essential» for all if it is made «essential.» There is no current necessity for it. The need has to be manufactured first. Hence the proclaimed «identity gap.»

Interoperability Is The Key

Biometric data records our «unique biological characteristics.» Fingerprints, iris-scans, DNA, facial recognition and voice-identification are all forms of biometric identifiers that can be stored digitally. Thales, the European defence and security contractor, explains how biometric data can be used for «biometric authentication»:

Biometric authentication compares data for the person’s characteristics to that person’s biometric «template» to determine resemblance. The reference model is first stored. The data stored is then compared to the person’s biometric data to be authenticated. [. . .] [I]ncreased public acceptance, massive accuracy gains, a rich offer, and falling prices of sensors, I.P. cameras, and software make installing biometric systems easier. Today, many applications make use of this technology.

Biometric digital ID is “mapped” to your physical ID. Thus, once we are coerced, forced or deceived into using it, we will always be identifiable on the planned surveillance grid.

Biometric ID is already commonly used around the world. In the UK for example, all driving licenses require machine readable photo ID; the Chinese government requires photo ID to purchase a SIM card or use the internet and has more recently moved toward issuing a national biometric digital ID card. So you may wonder why the G3P regime is developing new forms of biometric digital ID to meet SDG16.9.

Hitherto, all these disparate biometric ID systems have been managed by various national governments, their agencies and corporate partners, etc. Different forms of biometric digital ID are required for everything from license application and welfare claims, to accessing service or opening a bank account.

There is currently no unified, coherent international system of digital ID. This is a problem if you want to use it to exert centralised global governance control over «every person on the planet.»

The ID2020 Alliance was established to rectify the regime’s centralised authority problem. SDG16.9 enables ID2020 to claim legitimacy. For the people who think sustainable development has something to do with «saving the planet» or tackling the «climate emergency,» SDG16.9 is another untouchable “goal” and, therefore, must be implemented for the good of humanity.

ID2020 does not intend to stipulate the precise form of each national, regional or corporate ID card, nor every biometric data solution. Instead, by defining the «functional requirements» of all, the intention is to make every single one of these various digital ID products and services «interoperable.»

While each digital ID «solution» may have different design specifications, the biometric data they harvest will be machine readable in accordance with ID2020 technical standards. Thus, regardless of where or when the data is gathered, or by whom, it will be possible to create and maintain a single global biometric digital ID database.

As ID2020 states in its manifesto:

[. . .] widespread agreement on principles, technical design patterns, and interoperability standards is needed for decentralized digital identities to be trusted and recognized. [. . .] As such, ID2020 Alliance-supported pilots are designed around a common monitoring and evaluation framework.

Digital ID won’t necessarily be offered to all as a single “ID card”—or even as anything that appears to resemble a regime-controlled digital ID. Our SDG16.9 digital ID will instead be a composition of the data we share every day.

Private “vendors” of digital ID-based “solutions” will offer a “decentralised” range of products and services that people may adopt, perhaps without even realizing they are effectively committing to enter the regime’s digital ID network.

It will all depend upon the national government’s assessment of what their respective populations are willing to accept or are likely to reject. For example, people in China, familiar with concepts like “datong,” may be more amenable to accepting an official, government-issued digital ID compared to Westerners schooled in more libertarian traditions.

It should be noted that there is nothing “libertarian” about SDG16.9 digital ID. For populations that are stiffly opposed to government control, deception appears to be the preferred SDG16.9 “solution.” We will discuss that subject shortly.

ID2020 certification encourages the interoperability of the various digital ID products and services. It enables the «vendors» of digital IDs to «share a commitment to key principles for digital ID, but remain technology- and vendor-agnostic.»

The ID2020 Alliance recounts:

In January 2019, the Alliance launched the ID2020 Certification Mark at the World Economic Forum in Davos. ID2020’s Technical Advisory Committee (TAC), made up of leading experts on digital ID and its underlying technologies, established a set of functional, outcomes-based technical requirements for user-managed, privacy-protecting and portable digital ID.

With the net effect:

Through our Certification Mark, we shape the technical landscape to ensure that the digital ID solutions which are developed and adopted are user-managed, privacy-protecting and interoperable.

Interoperability is achieved through a digital ID platform’s compliance with the ID2020 Technical Requirements. Key Requirement 6.2 demands that all digital ID products and services:

Must support open APIs [application programming interfaces] for access to data and integration with components / vendors.

6.4 adds that digital ID systems:

Must be able to export the data in a machine-readable form. Data when exported, [. . .] should itself be provided in an open standard machine-readable format enabling ease of import into a new system/component.

The Founding «partners» of the ID2020 «Alliance» are Accenture, GAVI, IDEO, Microsoft and the Rockefeller Foundation. Their role is to establish the technical requirements for all digital ID “solutions” to enable the supposedly necessary, global “interoperability.”

Digital ID is not being implemented by «civil authorities» as the UN’s SDG indicator 16.9.1 deceptively suggests. Governments are merely the enabling and enforcement «partners» in the ID2020 – G3P. The design and functionality of global digital ID system is, and always was, led by the private sector.

The UN Digital Solutions Centre (UN DSC) has already established the digital ID framework for UN personnel. The regime has constructed “a suite of digital solutions that can be shared among UN Agencies.” This interoperability between all components of the «suite» enables the “personal, Human Resources, medical, travel, security, payroll and pension data” of UN workers to be centralised.

A modular “suite” of digital solutions that are «interoperable” is an important concept to grasp, as it effectively creates a single system of digital identity while giving the public the impression that there are instead many “decentralised” systems of digital identity. The ID2020 aim is not to create a single global digital ID system, but rather to construct a global network of interoperable digital ID “solutions” to feed the so-called «decentralised» data into a centralised global database.

The regime can then collate, analyse and exploit the harvested biometric data from a centralised, global command point. This will facilitate the global governance regime’s intention to surveil the Earth’s population. As yet, the universal biometric database hasn’t been officially announced, but the World Bank’s ID4D has emerged as a strong potential candidate.

The Global Interoperable Digital ID Database?

As a founding «partner» of GAVI, the World Bank has been a key ID2020 partner from the outset. The ID2020 Alliance is among the endorsing organisations behind the World Bank’s ID4D “dataset” project.

In turn, the World Bank has produced the Catalogue of Technical Standards for Digital Identification Systems. This outlines the ID4D mission:

The mission of ID4D is to enable all people to access services and exercise their rights, by increasing the number of people who have an official form of identification. [. . .] Trusted and inclusive identification (ID) systems are crucial for development, as enshrined in Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Target 16.9.

Recognising that many «vendors» are already developing digital ID «solutions,» the World Bank explains why it considers interoperability to be crucial:

Novel approaches, including decentralized and federated ID systems, are emerging rapidly along with new types of virtual and digital credentials. [. . .] The need for trusted and interoperable identification system has also intensified. Adherence to technical standards – henceforth “standards” – is one of the core building blocks of optimizing a system’s operations. [. . .] Standards are critical for identification systems to be trusted, interoperable and sustainable. The objective of this report is to identify the existing international technical standards and frameworks applicable across the identity lifecycle for technical interoperability.

The world “sustainable” is strewn throughout the regime’s written statements. By association, the intention appears to be to signal moral justification. In reality, “sustainable” here simply means “durable.”

The World Bank specifies the «standards» that it and its ID2020 partners expect digital ID products and services to comply with. It has divided these into five related categories.

Major standards to facilitate the technical quality and interoperability of the ID system related to: (1) biometrics, (2) cards, (3) 2D barcodes, (4) digital signatures, and (5) federation protocols.

Providing that developers comply with the stipulated standards, their digital ID solutions will be interoperable. For example India’s Aadhaar unique digital ID number uses «the ISO/IEC 19794 Series and ISO/IEC 19785 for biometric data interchange formats.» These are approved World Bank ID4D standards. In this case, Indian people’s biometric data can be exported in a “machine-readable format enabling ease of import into” the SDG16.9 compliant ID4D database.

Like ID2020, ID4D has formulated 10 principles for addressing the newly manufactured issue of the «identification gap,» a digital ID «gap» which ID4D claims to be an «obstacle for full participation in formal economic, social, and political life.»

The ID4D group states:

Growing awareness of the need for more inclusive, robust identification systems has led to a global call to action, embodied in Target 16.9 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). [. . . ] [T]here is no universally applicable ‘model’ for the provision and management of identity. [. . .] With this objective in mind, more than 15 global organizations have jointly developed a set of shared Principles that are fundamental to maximizing the benefits of identification systems for sustainable development[.] [. . .] These organizations have taken an important step towards developing a broad consensus on the appropriate design of identification systems and how they should—and should not—be used to support development and the achievement of multiple SDGs.

The ID4D and ID2020 organisations are supposedly distinct. Nonetheless, not only are their broad objectives practically identical, they are both supported by many of the same organisations:

ID4D is guided by the 10 Principles on Identification for Sustainable Development. [. . .] The work of ID4D is made possible through support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the UK Government, The French Government, The Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad), and the Omidyar Network.

The ID4D Global Dataset produces «a global estimate of the ID gap.» The dataset currently incorporates «self-reported data from ID-issuing authorities.» For example, it gathers data from «UNICEF birth registration and voter registration rates.» Covering 151 countries so far, the intended scope of the dataset, at the «global level,» is to eventually «include all people aged 0 and above.»

In July 2022, the ID2020 Alliance appointed Clive Smith as its new executive director. Clive was the former Director of Global Operations at the United Nations Foundation Mobile Health Alliance. Speaking about his new role, Clive said:

ID2020 can play a pivotal role, helping ensure that the appropriately interoperable solutions – and related financial, legal, and regulatory guardrails – are in place, and become the foundation of digital ID in the decades ahead.

While significant SDG16.9 progress has been made in developing and emerging economies, digital ID interoperability needs to be firmly established before enforcing digital ID upon the rest of the world’s population.

To aid developers to achieve interoperability, the ID4D partnership has launched the Modular Open Source Identity Platform (MOSIP). MOSIP is a modular software development environment based upon ID2020/ID4D «standards.» It was developed by the International Institute of Information Technology, Bangalore (IIIT-B) in Karnataka, India.

MOSIP enables other protocols to be converted into interoperable standards for data sharing. For example it uses OpenCRVS as a «global solution for civil registration.» This transcribes HL7 FHIR compliant birth registration records into a MOSIP compatible «registration.»

MOSIP-based digital ID products can thereby be assured that they are interoperable:

A fully interoperable digital civil registration system is key to enabling inclusive and equitable government service delivery.

Both public and private «vendors» can use MOSIP software modules to construct their own digital ID system while ensuring compatibility with ID2020 and ID4D «Key Requirements.» This will facilitate the «interoperability» which is crucial for ID2020 to provide digital ID to «every person on the planet» and for ID4D to «include all people aged 0 and above» in its database.

Thus, seemingly «decentralised» digital ID data can be centralised and SDG16.9 can succeed as intended.

SDG16.9: Key To “Sustainable” Stewardship Global Digital Goods

In 2021, the UN announced an initiative deceptively named «Our Common Agenda.» The planned future of humanity, as laid out by this initiative, includes a new «social contract anchored in human rights» and the regime’s claim that it has somehow managed to acquire the authority to better manage «global public goods.» From where they obtained such authority, no one knows.

The UN contends that «global public goods» are «those issues that benefit humanity as a whole and that cannot be managed by any one State or actor alone.» In ‘Our Common Agenda’ the UN asserts:

One of the strongest calls emanating from the consultations on the seventy-fifth anniversary and Our Common Agenda was to strengthen the governance of our [. . .] global public goods.

OpenG2P, which provides «government-to-person (G2P) solutions,» enables governments to provide digital «onboarding into schemes, identity verification, and cash transfers to their [the public’s] bank accounts.» According to the UN, OpenG2P is a digital public good.

Any organisation that professes to have the alleged right to exercise «stewardship» over something is claiming to define «the way in which they control or take care of it.»

Needless to say OpenG2P is World Bank ID4D and ID2020 standard compliant. This is just one «global public good» over which the regime intends to «strengthen» its global governance.

The WEF and the Rockefeller Foundation have partnered on the Commons Project. The claimed objective is:

Unlocking the full potential of technology and data for the common good.

Their stated mission is to “improve lives by empowering people to access, manage and share their data” by “supporting open data standards that promote interoperability”, “developing global ecosystems to convene public and private partners”; and “building technology platforms and services that empower individuals with their own data.” The Commons Project was notably behind CommonPass, a WEF-backed vaccine passport framework, as well as the Vaccine Credential Initiative (VCI), which sought to create the standards for interoperability among vaccine passports globally.

As reported by Unlimited Hangout in 2021:

[The Commons Project co-founders] Paul Meyer and Bradley Perkins, have long-standing ties to the RAND Corporation, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the International Rescue Committee, as noted in this article published last year by MintPress News. The IRC, currently run by Tony Blair protégé David Milliband, is developing a biometric ID and vaccination-record system for refugees in Myanmar in cooperation with the ID2020 Alliance, which is partnered with CommonPass backer, the Rockefeller Foundation. In addition, the ID2020 Alliance funds the Commons Project Foundation and is also backed by Microsoft, one of the key companies behind the VCI.

Having established the concept of exercising its governance over «global public goods,» the regime has moved on to flesh out the necessary policy platforms to convert its claimed authority into national government policy, regulation and legislation.

Everything related to global health care, including all of our health data, all information [on any subject] both online and off, all global economic activity, all trade and finance; the internet and all digital infrastructure, digital services, all data and «more.» The regime and its G3P regime claims both the authority and the ability to govern it all.

The regime states that 41 of the 92 SDG indicators cannot be met unless a system of «interoperable data and standardised reporting» is introduced. Therefore, they must fabricate the alleged geopolitical demand for said interoperable data and digital ID to meet the also fabricated «Identity gap.» Interoperable data solutions, especially digital ID, are essential if the regime is going to successfully exploit sustainable development to seize all global public goods and cement its claimed authority over it all.

As reported by Dr Jacob Nordangård, the commitment to «Our Common Agenda» gave rise to a number of policy briefs which governments around the world will «enable» and translate into hard national policy that controls all of us. Among the policy briefs sits the regime’s Policy brief No 5: A Global Digital Compact.

This blankly states, without any apparent justification or even identifiable rationale:

Digital technologies today are similar to natural resources such as air and water. Our well-being and development depend on their global availability.

Highlighting global inequality in the distribution and relative access costs of digital technology, the Digital Compact’s stated objective is «to overcome digital, data and innovation divides and to achieve the governance required for a sustainable digital future.» The deceptive moral “sustainable” case is made, ensuring most accept the proffered justification. The associated policy implications portend something far less edifying.

In A Global Digital Compact, the UN claims:

Urgent investments are needed in “data commons”, which pool data and digital infrastructure across borders, build flagship data sets and standards for interoperability and bring together data and AI expertise from public and private institutions to build insights and applications for the Sustainable Development Goals.

The regime and its partners have created the commensurate «mutlistakeholder» initiatives, the Digital Public Goods Alliance (DPGA) «where all recognised digital public goods can be discovered.» The DPGA brings together the usual foundations, such as the BMGF, the Rockefellers and the Omidyar Network, and other public and private «stakeholders.»

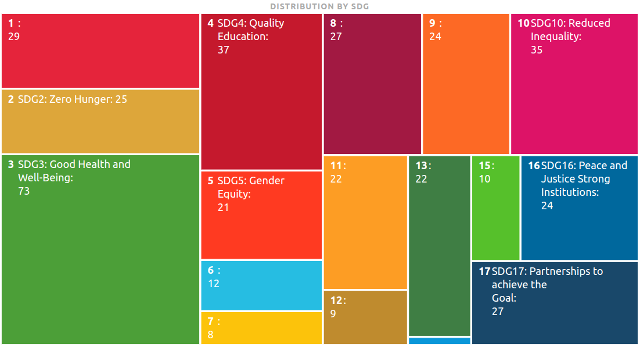

The DPGA has already registered a number of digital products which are, it says, essential for sustainable development. Apparently, 73 such products are necessary for SDG3 to transform global public health and health care; 25 digital public goods are needed in order for SDG2 to eradicate global hunger, 37 interoperable digital applications are allegedly essential for SDG4 to transform education and so on.

The DPGA claims that all registered Digital Public Goods (DPGs) must adhere to the DPG standards it decrees, along with its own set of «indicators.» This supposedly means that digital products that «store and distribute personally identifiable data, must demonstrate how they ensure the privacy, security and integrity of this data.»

The vendor must show, to the DPGA’s satisfaction, how it removes PII (personally identifiable information). How the DPGA can make this claim is a mystery as the global governance regime clearly intends to collect PII as outlined in A Global Digital Compact:

Personal data should only be collected for specified, explicit and legitimate purposes, and their processing must be relevant and limited to what is necessary for those purposes.

The regime will specify the «legitimate purposes» for the “collected” PII. We already know that some of those purposes include ensuring our health data is «bound to an individual identity.» ID2020 founders Accenture are among the digital ID vendors whose blockchains and biometrics will support their corporate clients to «map physical IDs to digital IDs.» Presumably, this too is «legitimate.»

Other legitimate purposes include the surveillance of every transaction we make. It is clear that the intention is to link our digital IDs to our finances. The Global Digital Compact adds:

Digital IDs linked with bank or mobile money accounts can improve the delivery of social protection coverage and serve to better reach eligible beneficiaries. [. . .] Digital public goods and applications such as mobile money are enabling access to financial and other services for all members of societies.

The regime maintains that this is “legitimate” because it establishes the framework for another of its deceptively named ideas: financial inclusion.

Digital ID and «Financial Inclusion«

The regime’s concept of «financial inclusion,» as highlighted in its Global Digital Compact, will see our digital IDs linked to our «bank or mobile money accounts.»

This will not only enable the regime to take our money whenever it likes, for whatever purpose it wishes, but also to surveil and control all of our transactions and effectively operate a global system of economic punishment and reward. SDG16.9 is thus the keystone for a global dictatorship.

The UN Secretary-General’s Special Advocate for Inclusive Finance for Development (UNSGSA), in partnership with the G20, has identified fixing the lack of financial inclusion as «imperative» for meeting SDGs:

G20 leaders recognized financial inclusion as a cross-cutting issue for development and economic system stability and included it in work plans. Additionally, financial inclusion is referenced in the targets of eight of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). [. . .] An important step on the global level was to convene financial standard-setting bodies (SSBs) at the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) in Basel to include financial inclusion in their work.

UNSGSA is led by Queen Máxima of the Netherlands who, as a former economist for Deutsche Bank and institutional sales director for HSBC—among her numerous roles with other global financial institutions—is working with the WEF, the World Bank and the BIS to unlock the estimated $2 trillion in investment required to achieve said «financial inclusion.»

India—and China—are of particular interest in this regard. In its most recent (financial inclusion index) Findex Report, speaking about the need to create the $2 trillion «enabling environment,» the President of the World Bank, David Malpas, said:

The lack of verifiable identity is one of the main reasons why adults remain excluded from financial services. India has pioneered a successful model for universal identity[.] [. . .] The interoperability of systems and the availability of a low-cost switch for financial transactions are equally important.

The UN offers an explanation, suggesting why its focus upon “financial inclusion” supposedly matters:

According to the 2021 World Bank Global Findex. [. . .] Financial inclusion [. . .] has a critical role in the efforts to help people prepare for, respond to and recover from crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, inflation, or economic and climate shocks. [. . .] An inclusive financial system is essential infrastructure in every country.

Once again we see that crises provide opportunities. As stated here, a variety of crises, new and old, will be used to push for “financial inclusion.”

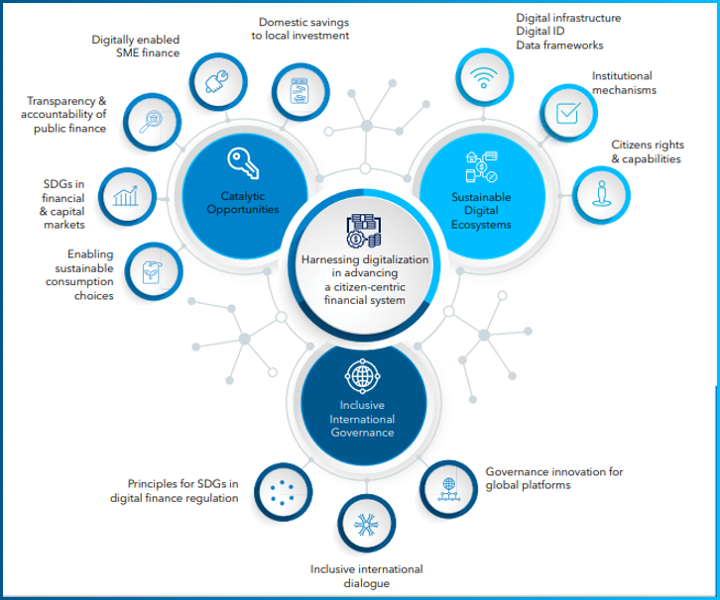

The UN Task Force for the digital financing of SDGs explored how to “catalyse and recommend ways to harness digital financing to accelerate the financing of the Sustainable Development Goals.” It published a “call to action” with the objective of exploiting “digitalization in creating a citizen-centric financial system aligned to the SDGs.”

The UN Task Force’s “action agenda” recommended “a new generation of global digital financing platforms with significant cross-border, spillover impacts.” According to the regime, this would, of course, require the strengthening of “inclusive international governance.”

Cross-border spillovers, or «externalities,» are the actions and events occurring in one country that have intended or unintended consequences in others. An article published by the private World Privacy Forum, the BMGF and the Rockefeller-backed Centre for Global Development, after noting that COVID-19 accelerated the path towards digitalisation, claimed that governments are “still in the early stages of deciding how they want to govern digital spaces.” Apparently, the only possible solution is, as the UN Task Force claims, tighter global governance.

It is claimed that cross-border spillover could be managed by including “digital ID and data markets” in a system of “SDG-aligned digital financing.” Supposedly, this will enable people to exercise their [human] “rights” while protecting national economies and data markets from spillover impacts.

Such [human] “rights” include the “right” to have a digital ID attached to an individual from birth in order to ensure that any “money” allocated to any individual can be used by the G3P to finance whatever it wants to finance.

The Task Force concluded that the “catalytic opportunities” to finance SDGs would necessitate “accelerating the use of domestic savings” and controlling “SDG-aligned consumer spending.” The proposed “citizen-centric financial system” provides the G3P regime access to domestic savings and the power to supervise consumer spending.

To this end, in 2020, the UN Task Force published a document it deceptively titled “Peoples’ Money – Harnessing Digitilisation to Finance A Sustainable Future. The most striking thing about “Peoples’ Money” is that the global governance regime assumes that all of the peoples’ money belongs to it:

The aggregate global pool of domestic savings has grown over the last 20 years from US$7.5 trillion to US$23.3 trillion. Domestic savings in least developed countries alone has grown from US$13 to US$218 billion over the same period. Digitalization allows micro-savings from the informal sector to become part of the formal financial system and gives those already using the financial system more options. This raises the possibility of increasing the proportion of long-term development financing needs being met from domestic resources.

The Financial Times offers a reasonable definition of “domestic savings”:

Gross Domestic Saving consists of savings of household sector, private corporate sector and public sector.

As we will discuss in a moment, none of us have the right to not to be included in this digital ID based financial system. It is assumed that all of us agree that “our” money should be used to finance the UN regime’s SDGs.

The long-term development of financing for SDGs can come directly from “our” bank accounts in the digitalized “ecosystem.” This is another notable aspect of the UN regime’s “citizen-centric financial system.”

“Peoples’ Money” recommended that the UN and its partners should use “the forces of digitalization” to accelerate SDG-aligned, citizen-centric financing:

Digital identity systems are particularly important for people to be able to operate in this world. [. . .] Robust, accessible, affordable and secure digital foundations are a pre-requisite to citizen-centric, SDG-aligned finance. This includes the core digital connectivity and payments infrastructure, digital IDs, and data markets that enable financial innovation and low-cost service delivery. [. . .] Universally-available, reliable, secure, private, unique digital IDs are critical to enabling people to access digital finance.

«Financial inclusion» renders our access to money and finance subject to conditions set at the global governance level. It converts us all into “cash cows” on a global financial farm.

While we may still be able to access funds—if we have an approved digital ID—we won’t control our own money. The money we can “access” can be expropriated for SDG investment and keeping our money elsewhere will become more difficult as “the informal sector” becomes “part of the formal financial system” through the imposition of these systems globally. Digital ID «linked with bank or mobile money accounts» is the key to unlock the «informal sector» vault.

SDG16.9 digital ID is essential for the new SDG-aligned financial system to thrive. Imposing a global system of of digital identity for all eight billion of us is a mammoth task. The Task Force reiterated the only practical, technological solution:

Open source projects and shared standards allow interoperability and open innovation rather than tying companies into proprietary technology and locking data into incompatible formats.

UN Task Force action plan to create a citizen-centric, SDG-aligned financial system. Source

Controlling All Business Through Digital ID

Financial inclusion extends beyond the individual to all of our businesses. The regime claims the “right” to “steward” all of those assets too.

In 2021, Manjeet Kripalani, the Executive Director of Gateway House (Indian Council on Global Relations), the Indian policy think-tank arm of the US Council on Foreign Relations, wrote:

Digitalisation will power the developing world out of economic crisis with MSMEs [Micro-, Small and Medium Enterprises] as a necessary enabler.

The regime considers MSMEs—i.e. our businesses—to be crucial to achieving a number of SDGs. Consequently, the regime claims the authority to govern our businesses. This will enable it to lead the «structural transformation that provide[s] a regulatory framework conducive to their [MSMEs] growth.»

Three hundred of the world’s largest financial institutions agree and have recognised how digital ID could help MSMEs unlock «trade finance.» Trade financing is a credit product that global corporations offer to «help traders manage their international payments and associated risks.»

This is all supposedly necessary because a series of crises have stifled MSMEs’ access to financing, they claim. The irresponsible lending policies of the financial institutions had nothing to do with it apparently.

In order to help MSMEs, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) suggests that «improved automation of corporate digital identity (DID), combined with technologies to digitise trade documents and to process alternative credit data, offer promising solutions.»

The BIS adds:

In the context of trade finance, DIDs [Decentralised Identifiers] also need to be harmonised across borders, highlighting the need for common standards. Once achieved, corporate DIDs can integrate with other trade tech solutions [. . .]. For example, combining faster and more well rounded credit assessments with the use of alternative data and trade document digitisation can speed up and enhance credit extension to SMEs [small to medium size enterprises].

DIDs are “Decentralised Identifiers.” They can be assigned to corporations, small businesses and individuals. We’ll cover this in more detail shortly.

While it is heartening to know that the largest and most powerful financial institutions on Earth are eager to help our small businesses, obviously we’ll only get that «help» if our businesses have the right digital ID [DIDs]. We might also wonder if a single, global system controlling all business investment and finance is likely to benefit our cafés, small industrial contractors, craft workshops, hair salons and other MSMEs.

Digital ID for MSMEs is part of the regime’s “citizen-centric financial system.” Although it appears to be far more multinational financial corporation «centric» than “citizen-centric.”

In the Digital Compact, the UN states that it wants to established a «global commission» to oversee the transition to interoperable, digital ID-based digitalisation. It also notes:

Digital technologies are accelerating the concentration of economic power in an ever smaller group of elites and companies: the combined wealth of technology billionaires, $2.1 trillion in 2022, is greater than the annual gross domestic product of more than half of the Group of 20 economies. [. . .] The present policy brief builds upon the foundation laid by the report of the Secretary-General’s High-level Panel on Digital Cooperation.

Crises, such as the pseudopandemic, always tend to significantly increase the wealth of the so-called «elite.» The most recent wealth transfer to tech billionaires transpired as a result of the digitalisation that blossomed during the pseudopandemic.

As pointed out by independent journalist and documentary filmmaker James Corbett, it is therefore preposterous that the «Digital Compact» is based upon the work of the High-level Panel on Digital Cooperation which is led by ultra-wealthy figures like Melinda Gates, Co-Chair of the BMGF, and Jack Ma, Executive Chairman of the Alibaba Group.

James Corbett observed:

Digitisation [digitalisation] has meant the creation of this incredible billionaire super-class that is now having more and more power over greater and greater sections of our lives as everything becomes digitised. So what is the UN’s answer to this? [. . .] Who are they entrusting to solve the problem they have created? It’s the people who created the problem. It is absolute insanity.

It certainly appears insane, but only if you think sustainable development has anything to do with prioritising «the essential needs of the world’s poor.» If you understand, as James Corbett does and has been reporting for many years, that sustainable development is about enhancing and centralising global power, then, the fact that people like Gates and Ma are guiding policy development makes perfect sense.

Digital ID Whether You Want It Or Not

In Mario Puzo’s novel, The Godfather, the character Don Vito Corleone says «I’m going to make him an offer he can’t refuse.» SD16.9 digital ID is being «offered» to every person on the planet using the same, fabled gangster’s ploy of a «choice» between agreement or dire consequences. Or, at least, that is the apparent nature of the coercion.

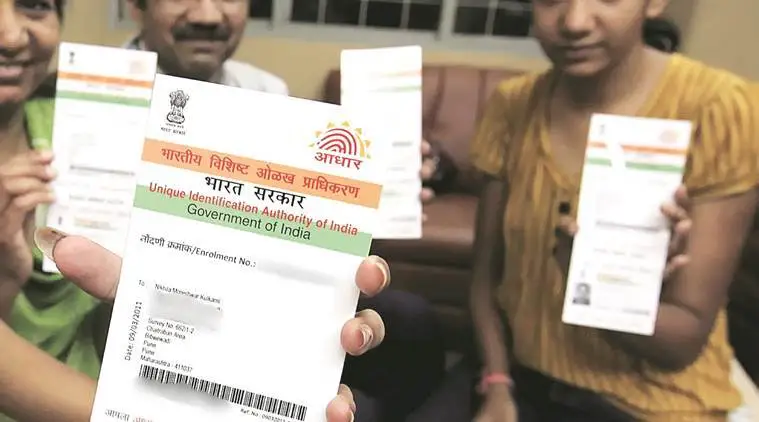

The regime reports that 2023 is likely to be the year that India overtakes China as the world’s most populous country. The global governance regime and its partners made significant strides towards coercing all Indian people to use its ID2020 compliant, interoperable digital ID by supporting the development of the Aadhaar system in India.

The regime’s ID2020 founding partners, such as the Rockefeller Foundation, have been deeply involved with development of the Aadhaar program in India:

With the support of the Rockefeller Foundation, ID2020 partnered with IDinsight to identify metrics which would capture feasible, actionable and generalizable data on digital identity programs. [. . .] The State of Aadhaar initiative, hosted by IDinsight, aims to catalyze data-driven discourse and decision-making in the Aadhaar ecosystem.

The objective was to ensure that the Aadhaar «ecosystem» met ID2020 and ID4D standards and interoperable «functional requirements.»

The Aadhaar 12 digit ID registration number has been adopted by an estimated 90% of India’s 1.4 billion people. This is managed under the statutory authority of the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) by virtue of the Aadhar Act of 2016.

The UIDAI founding chairman is the Indian multi-billionaire Nandan Nilekani. He is both a close friend of Bill Gates and a member of ID4D High Level Advisory Council which provides «strategic guidance to the ID4D Initiative.»

The BMGF, an ID2020 co-founder, has been equally supportive of Aadhaar. The BMGF—also a leading UN partner—is ostensibly very concerned about «financial inclusion.» Consequently, the BMGF, has established its Financial Services for the Poor project:

Our team is actively exploring ways to accelerate use of digital financial services. [. . .] We also are working to promote the development of effective identification systems in priority geographies. ID platforms such as the Aadhaar system in India are promising models for providing safe, efficient, and widely beneficial identification services that support financial inclusion across a country.

According to the UN and the BMGF, with the support of the Rockefeller Foundation, the Aadhaar Digital biometric ID system, once linked to an «inclusive financial system,» will be «essential» for all Indian people.

The mAadhaar app. Source

The UIDAI explains the Aadhaar registration process:

The process for Aadhaar enrolment of resident of the country involves use of certain basic demographic information combined with ten finger prints, both irises and photograph to uniquely identify a resident.

The biometric data, mapped to «a person’s physical ID,» will be available to vendors who have «approved» access to the data. The plan is to «decentralise» access to the inevitable global database, through MOSIP or similar “trust frameworks,” thus supposedly improving data protection.

Nearly 1.3 billion people in India have every aspect of their identity, from name and address to identifying biometric data, stored on a single, centralised database: the Central Identities Data Repository (CIDR).

The UIDAI claims that applying for an Aadhaar card or using the mAadhaar app is voluntary. This is only true in Don Corleone sense.

The Aadhaar card enables Indians to access much needed subsidies, benefits and services. This was always the intention of the UIDAI, pursuant to the 2016 Act.

Other forms of ID are available, but the UIDAI has now stated that either an active or proof of a pending Aadhaar Enrolment Identification (EID) number will be needed to claim state benefits.

The Permanent Account Number (PAN) card is what enables Indians to pay their taxes. They face an automatic fine of Rs. 1000—additional fines levied on-top as deemed necessary—if they fail to do so. The PAN also facilitates the purchase and sale of vehicles, the opening of all but the most basic bank accounts, credit card applications, bank payments and transfers of Rs. 50,000 ($600 USD) or more, etc.

The Indian Government decreed that all PAN cards were to be linked to an Aadhaar system buy June 30th 2023. PAN cards have now been phased out. Those who missed the deadline can pay a penalty to link their EID retrospectively but, if they can’t afford the penalty or don’t know what to do, according to Microsoft, that’s just too bad.

The Election Commission of India (ECI) is trialling the linking of Aadhaar digital ID to voter registration. This will not become «mandatory» it claims.

It is, therefore, no wonder that Aadhaar uptake is so high. Providing you don’t need and will never need any state benefits or subsidies, and as long as you don’t run a business or are required by Indian law to pay tax; if you don’t have or ever want any credit and don’t wish or need to access a bank account; if you never buy or sell a car and don’t ever spend more than the equivalent of $600 USD and, in all probability, never wish to vote, then your Indian biometric digital ID is entirely «voluntary,» in theory.

India is a vast country. In reality, Aadhaar is not and has never been «voluntary» for the majority of Indians.

In Kerela, the voluntary Aadhaar link to voter registration operates on an opt-out basis, but residents are not routinely made aware of this. The Tamil Nadu state government, legislating nearly 84 million people, has issued a series of orders mandating Aadhaar for access to state benefits and subsidies.

Notably, Aadhaar has been plagued with technical errors and data breeches. In its 2019 Global Risks Report, the WEF reported:

The government ID database, Aadhaar [CIDR], reportedly suffered multiple breaches that potentially compromised the records of all 1.1 billion registered citizens. It was reported in January that criminals were selling access to the database at a rate of 500 rupees for 10 minutes, while in March [2018] a leak at a state-owned utility company allowed anyone to download names and ID numbers.

In 2018 and in response to persistent allegations of CIDR vulnerabilities, R.S. Sharma, Chairman of the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI), in an effort to demonstrate that these were all “conspiracy theories,” published his Aadhaar number on Twitter to prove the system was secure. Within hours, interested parties had released his mobile number(s), Gmail and Yahoo addresses, physical address, date of birth, frequent flyer number, personal photographs and bank account details to which, for comedic effect, they sent some small payments.

Older people, whose fingerprints have degenerated, have been excluded from accessing vital food subsidies due to the flaws in Aadhaar’s biometric component. In 2015, a study revealed that of 85,589 ration card holders—accessed via Aadhaar—50,151 people in Andhra Pradesh could not access the grain subsides provided through 125 fair price shops across the state.

Eight years later, there is little evidence that the problem of «exclusion» has been resolved by this system. Indian states operate various «vetting» procedures as a prerequisite to issuing Aadhaar ID. Vetting has been used to discriminate against disadvantaged populations. For example, Adivasi people, who often do not possess birth certificates, have been excluded from financial benefits and food relief, as they have been blocked via the vetting procedures and can’t obtain an Aadhaar EIN.

The Aadhaar system has also frequently encouraged, rather than deterred, widespread corruption. In Jharkhand, grain dealers used Aadhaar to record the allocation of grain quotas but halved the amount supplied to aid recipients, selling the remainder for illegal profit.

The SDG16.9.1 indicator aims to measure the «proportion of children under 5 years» who have digital ID. It is no coincidence that the Nilekani’s UIDAI seeks to capture «biometric identity for minor children below five years.»

It is the poor who are worst affected by alleged registration and vetting «errors.» Tens of millions of impoverished Indian children are at risk of exclusion from school and essential food subsidies.

Once again, we are confronted with the stark contrast between the stated aim of sustainable development—-to give priority to «the essential needs of the world’s poor»—and the reality. So frequent is this disconnect that it is reasonable to conclude that empowering the world’s poor is not the intention at all.

The regime is so impressed with its Aadhaar system that its ID4D agent, the World Bank, is working with the UIDAI to export the Aadhaar model globally to create a «Universal Global Identity System.» While this appears to be extremely bad news for the world’s poor, Saurabh Garg, chief executive of UIDAI, said:

The Universal Global Identity System is something we are very actively working upon. [. . .] [S]ome countries have already adopted the kind of architecture that we have used and others are keen to do that.

By July 2022, the IIIT-B MOSIP development platform had been used by digital ID vendors to supply interoperable Aadhaar-like ID products and services in Sri Lanka, Morocco, the Philippines, Guinea, Ethiopia and the Togolese Republic. By April 2023, Uganda, Sierra Leone and Burkina Faso had also adopted MOSIP interoperable digital ID.

We can only hope that this will do something to tackle the disastrous impact that SDG16.9 has already wrought on countries like Uganda. Unfortunately, there is no reason to think that it will.

Known in Uganda as «Ndaga Muntu,» and widely recognised as a national security “weapon,” the Ugandan National ID Card (NIC) is needed for everything from accessing healthcare, food aid and financial support, to applying for licences and opening bank accounts.

In 2021, the Ugandan human rights watchdog “Unwanted Witness” published its report on digital «exclusion» entitled «Chased Away and Left To Die.» Unwanted Witness academics recorded a litany of abuses and cruel exclusions that had been facilitated by Ugandan digital ID.

Ugandans had to bribe officials to gain the necessary «sanctioned» signatures for their digital ID applications. Non-indigenous Ugandans, such as the Maragoli people, were routinely excluded from accessing digital ID. Older and disabled people with difficulty accessing remote registration centres and often with degraded biometric features, such as irises and fingerprints, were also systematically «excluded.»

With an estimated 23% -33% of Ugandan adults excluded from digital ID registration, many resorted to unorthodox means to access vital services. Forgery, submitting false names, posing as others already registered and bribing officials were common tactics.

Much of this was «illegal,» running the risk of punishment and arrest, but unavoidable for millions of Ugandans. A woman in the Ugandan district of Amudat told the researchers:

Without an ID or clinic card for women who have been receiving antenatal care, [you will receive] no treatment. Many people fall sick and stay home and die.

These problems were compounded by high error rates in the registration and data handling processes. 50,000 of 197,000 Ugandans over the age of 80 could not collect their Senior Citizens Grants [UK and Irish-supported state pensions] as a result.

The Ugandans that were able to register for digital ID were also placed at risk. Following anti-government protests in 2020, the Ugandan police used registered biometric facial recognition from the NIC database to identify protesters and arrested more than 830 of them.

The offer no one can refuse has already been made to billions of people in developing and emerging economies and is beginning to be rolled-out in developed economies, such as Russia, the UK, US, the EU and elsewhere.

The World Bank’s most recent Findex Report noted:

Global efforts to increase inclusive access to trusted identification systems and mobile phones could be leveraged to increase account ownership for hard-to-reach populations.

This «leveraging» is particularly important to coerce the people who neither want a bank account nor the digital ID that goes with it: the so-called “unbanked.”

The World Bank’s report adds:

Distrust of the financial system is a greater barrier in some regions, and globally it was cited by 23 percent of unbanked adults. In Europe and Central Asia and in Latin America and the Caribbean, about a third of unbanked adults said they do not have an account because they distrust the banking system. In Ukraine, 54 percent of unbanked adults listed distrust in the financial system as one of the reasons for their lack of an account. More than one in three unbanked adults cited the same barrier in Argentina, Bolivia, Bulgaria, Colombia, Jamaica, and Russia, among others.

It seems these “unbanked” people do not have the «human right» to decline a bank account or reject the imposition of digital ID. Yet, they are all currently surviving without either. The fact that so many people currently live without them, shows us that this «offer» is essentially a confidence trick.

While the «choice» to refuse digital ID won’t be easy, it can still be done, including in developed nations. It is certainly time for us all to start considering our options very carefully, because SDG16.9 digital ID is taking us all to a very dark place.

Digital ID-Based Central Bank Digital Currencies & Financial Inclusion

The SDG-aligned, «citizen-centric» financial system will almost certainly be based upon interoperable Central Bank Digital Currency. CBDC, linked to digital ID, enables the necessary allocation and control of our «money.» If the plan succeeds, all money will be a direct liability of the central banks. Such “money” will always “belong” to central banks, never to us.

This explains why the Bank for International Settlements (BIS)—the central bank of central banks—claims that CBDC could be an effective tool for financial inclusion.

A digital platform that enables a public-private partnership of «vendors» to integrate their products and services to a centrally controlled «portal,» has emerged as the foremost model for the «global digital transformation.» The «platform model» is preferred by governments around the world for a range of digital ID-based «services.»

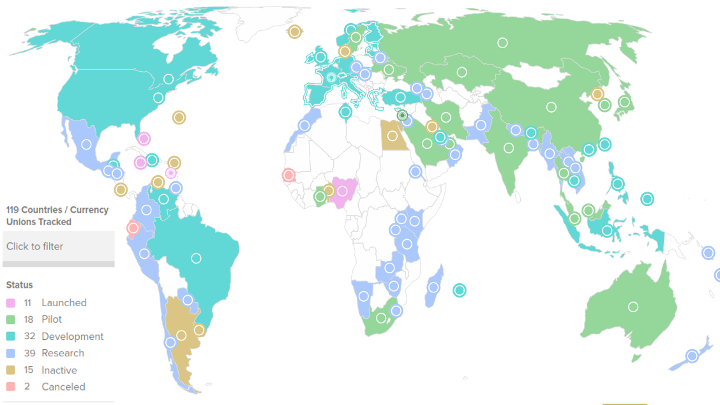

According to the NATO-aligned Atlantic Council’s CBDC Tracker, «130 countries, representing over 95 percent of global GDP, are exploring a CBDC.» Of these, 11 have launched a full national CBDC. Of the 11, Nigeria, with a population of more than 220 million people, is by far the largest.

The nations leading development of the multipolar world are leading the CBDC race. Source

Access to Nigeria’s e-Naira is dependent upon possession of a National Identification Number (NIN) authorised by the National Identity Management System (NIMS) programme. The most significant national CBDC launched to date requires Nigerians to use digital ID. Their «human rights» do not extend to maintaining anonymous financial transactions.

The Bank for International Settlements states:

Universal access to eNaira is a key goal of the CBN [Central Bank of Nigeria], and new forms of digital identification are being issued to the unbanked to help with access. [. . .] When it comes to anonymity, the CBN has opted to not allow anonymity even for lower-tier wallets. At present, a bank verification number is required to open a retail customer wallet.

Nigerian’s NINs compel them to share all their biometric data with the government and its commercial partners. By linking this to the e-Naira, Nigerians’ transactions can be surveilled and tracked and, more importantly from the global governance regime’s perspective, controlled.

The CBN launched the e-Naira in November 2021. In December 2021, the ID4D partnership began its Nigeria Digital Identification for Development (ID4D) project. Similarly, in China, digital ID is required to use the e-CNY—China’s CBDC.

CBDC and digital ID are synonymous. This was always the intention. In its 2021 Annual Economic Report, the BIS wrote:

[T]he most promising design is an account-based CBDC, rooted in an efficient digital identity scheme for users. In this way, CBDCs can meet the challenges raised by the huge volume of personal data collected as an input into business activity. [. . .] CBDCs are best designed as part of a two-tier system where the central bank and the private sector focus on what they do best: the central bank on operating the core of the system by ensuring sound money, liquidity and overall security; the private sector by innovating and using its creativity and ingenuity to serve customers better.

As will be detailed shortly, the “two-tier” system is designed with deception in mind. It means that we can be tricked into using both CBDC and the prerequisite digital ID without our knowledge. Not only will we have been ensnared in the regime’s “citizen-centric financial system,” we will also be registered on the “Universal Global Identity System” without ever consciously giving our consent.

In addition, CBDC is «programmable money.» This means that digital «smart contracts» can be linked to individual transactions, thus enabling policy enforcement.

Bo Li, the former Deputy Governor of the PBC, and the current Deputy Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), speaking at the Central Bank Digital Currencies for Financial Inclusion: Risks and Rewards symposium, explained the power that programmable CBDC «financial inclusion» affords the G3P regime:

CBDC can improve financial inclusion through, what we call, programmability. That is, CBDC can allow government agencies and private sector players to program [CBDC] to create smart-contracts, to allow targeted policy functions. For example[,] welfare payments [. . .], consumptions coupons, [. . .] food stamps. By programming, CBDC money can be precisely targeted [to] what kind of [things] people can own, and what kind of use [for which] this money can be utilised. For example, [. . .] for food.

Policies will be enforced by a global public-private partnership. These policies can be implemented at the point of sale, removing the need for legislation or any democratic process. Access to food, water, energy, or money can be controlled by the G3P regime.

15 minute cities can be established and enforced by disabling a user’s CBDC beyond a 15 minute radius from their homes. The use of Electric Vehicles (EVs) can be compelled by disabling the CBDC purchase of any petrol or diesel vehicle or by denying the buying of tickets for non-EV public transport. All business activity, investment and financial services can be controlled. Interoperable CBDCs, supposedly designed to meet the SDG16.9 financial inclusion, is feudalism at best but can also be considered global slavery.

The UK government is one of the leading financial backers of the World Bank’s ID4D global digital ID «data set.» It is also a keen advocate of CBDC. So it is not at all surprising to see the UK state broadcaster, the BBC, provide the appropriate e-Naira guidance in Pidgin.

The Nigerian state is trying to force its population to use its digital ID-based CBDC. The CBN has strangled the supply of cash, leaving Nigerian bank customers unable to acquire the physical money they need. This has resulted in numerous protests, as Nigerians resist the imposition of CBDC.

The Nigerian people are not falling for the coercive tactics of the central bank and the government. They are turning instead to other forms of payment and are demanding renewed access to cash. So far, the roll-out of the e-Naira has been a total flop.

The unpopularity of CBDC has coincided with a significant increase in the use of cryptocurrency in Nigeria. The Nigerian Government response is as expected. It continues to try to regulate cryptocurrency, but with little success. It seems Nigerians don’t want «financial inclusion.»

The Indian government has been far more aggressive in preparation for the imposition of CBDC in the form of the e-rupee. In 2016, it began the process of «demonetisation,» removing 86% of Indian cash overnight. This forced Indians to use electronic banking, priming them for their impending CBDC.

Nonetheless, the e-rupee is not popular in India either. Just as in Nigeria and China, the people wisely view CBDC with immense suspicion. Unfortunately, the global public-private partnership (G3P) regime isn’t interested in our opinions or wishes.

Apparently demonstrating unbelievable naivéte, when Cornell University researchers investigated why the e-Naira had failed, they noted:

Unfortunately, the anti-laundering measures [ALM] built into the eNaira can be seen by users as a breach of privacy, with the government able to monitor all your money and potentially use that information for control. [. . .] The eNaira seems to have been created to preserve as much government power as possible. Nodes are run in private, and no transaction details are shared with the public, so usage statistics remain visible to the CBN only. The strict authentication measures make government tracking incredibly viable, while not really giving any real accountability to the government.

The scholars seemingly thought this was a design flaw. However, it was not a mistake. As the BIS pointed out, that is how CBDC is intended to function. It is the CBDC “model.”

Pedro Magalhães, a Brazilian software engineer and blockchain developer, reverse-engineered the published code for the Brazilian CBDC. He discovered that it could adjust account balances, make payments and generate or eliminate “digital tokens” without user permission.

In addition to «financial inclusion,» another alleged benefit of CBDC is «financial stability.» The threat of another global financial crisis has been sign-posted by the regime on innumerable occasions. CBDC may well be offered to all as the «global solution» to the next «global financial crisis.»

If the central banks that seek to promulgate CBDC continue with their apparently reckless and groundless monetary policies, a global financial crisis is all but inevitable. Once again, policy, not random events, will be the driver. Perhaps central bank monetary policy is not as «reckless and groundless» as some imagine.

CBDC is the ultimate “tool” to control the citizen-centric financial system. Digital ID will be required for anyone to access CBDC. Digital ID is clearly the “pre-requisite to citizen-centric, SDG-aligned finance.”

Biometric Digital ID Via Two-Tiered Platforms

Digital ID is perhaps the most crucial technological component of the regime’s sustainable development agenda. Nearly all nation-states have committed to fulfilling SDG ambitions, including the widespread adoption of biometric digital ID.

Simultaneously, “financial inclusion,” the fluffy-sounding regime term for financial control, is a core component of SDG financing. Ubiquitous use of biometric digital ID is synonymous with our planned future access to “money.” What better way to get everyone to “onboard” onto the new system than to exclude them from the essential financial and banking services if they do not participate.

The problem the G3P regime faces is that the availability of potential alternatives—whatever maintains the possibility for anonymous transactions, such as cash, local exchange trading systems (LETS) and some cryptocurrencies—can be used by people who decline the offered tyranny. This point is exemplified by the Nigerian peoples’ reaction to the eNaira.

The rollout of CBDCs and the prerequisite digital ID has so far been a disaster for the regime. Regardless of the culture, people in India, China and elsewhere have shown a distinct lack of enthusiasm for embracing their planned digital future. In fact, they are actively resisting in many instances.

It now seems clear that, absent some destructive financial event—a financial Pearl Harbour that would potentially enable the G3P to offer CBDC as the only possible “solution”—the G3P regime can’t impose its digital ID products and services nor achieve digital “financial inclusion” purely by coercion or force.

Consequently, the G3P is evidently willing to use subterfuge. The adoption of the “two-tiered” model of CBDC facilitates their deception.

There are many different technical models proposed for central bank digital currencies (CBDC). Broadly speaking, though, CBDC is either “wholesale” or “retail.”

Wholesale CBDC acts like central bank reserves. It is available for use only by commercial banks, financial institutions and central banks. They use wholesale CBDC to settle payments between each other, but it is not accessible to the general public.

Retail CBDC, on the other hand, is offered to the public. It is promoted as an “alternative” to both cash and the electronic payment systems we commonly use, which can also be considered fiat currency—“cash”—transactions.

With the launch of the e-CNY, the eNaira, the e-Rupee, the digital pound and the digital ruble, the “hybrid” or “two-tiered” model has emerged as the preferred CBDC “platform.” This model of CBDC is issued by the central bank via an application programming interface (API). Private financial institutions and firms can then access the API and use CBDC for wholesale settlements.

The two-tier model also allows private commercial banks and payment “solution” providers—Mastercard, Meta, PayPal or WeChat Pay, for example—to “innovate” and construct financial products and services on the API “layer.” All of these banks and providers are effectively offering the public “retail” CBDC transactions on a single “two-tiered” infrastructure that also enables “wholesale” settlements.

The BoE’s digital pound technical specification explains how the two-tiered CBDC model will function. Private financial institutions and payment providers, which the BoE calls PIPs and ESIPs respectively, will be given the power to program the digital pound via, for instance, the smart contracts favoured by Bo Li and others.

The BoE states:

The [two-tier] platform model is currently the preferred model for offering a UK CBDC. [. . .] The Bank hosts the core ledger and an application programming interface (API) layer. The API layer would allow private sector firms, known as Payment Interface Providers (PIPs) and External Service Interface Providers (ESIPs), access to the core ledger functionality in order to provide user services. Access to the core ledger would be subject to approval by the Bank [. . .] and subject to PIPs and ESIPs having appropriate regulatory status.

The two-tiered CBDC model incorporates all the functionality of other CBDC systems, such as instant cross-border settlement and programmability, but provides the possibility that the public could be lulled into using a CBDC without necessarily knowing that it is one as they would not directly interact with the CBDC’s API. The same can be said for the accompanying biometric digital ID.

The underlying currency will be CBDC but, as the BoE points out, the products and services that use CBDC could take many different forms, anything from stablecoins to non-fungible tokens (NFTs):

[The] ledger records updates to the state and ownership of tokens or the destruction and creation of unique tokens. [. . .] Technologies for a CBDC are also relevant to privately issued digital money, like stablecoins. [. . .] PIPs could implement some [. . .] features, such as automated payments and programmable wallets, by hosting the programmable logic, and updating the core ledger with the result via the API. But other features, such as payment-versus-payment (PvP) [. . .] and smart contracts, might require additional design considerations. In those instances, the Bank [BoE] would only provide the necessary infrastructure to support PIPs and ESIPs to provide these functionalities. [. . .] PvP functionality might be used to enable interoperability and exchange between a CBDC and other forms of money, such as stablecoins.

It is worth reiterating that while the two-tier model allows commercial banks and others to develop all manner of digital payment products and services, the underlying currency for the settlement of all payments, both wholesale and retail, is CBDC. While the BoE claims that it doesn’t “currently” intend to program CBDC directly, preferring to leave this to PIPs and ESIPs for the time being, it stressed that the base “CBDC must deliver the government and Bank’s [BoE] policy objectives.”

For private financial corporations to maintain access to the CBDC “infrastructure,” they “must deliver” G3P policy objectives, such as SDG “financial inclusion.” The BoE will control the “core ledger” and the PIP and ESIP license approval process. While the “two-tier” model appears to be “decentralised,” or “vendor agnostic,” it is actually a stringent, programmable, “centralised” financial control system.

The BoE acknowledges that it is wary of public resistance to its authoritarian control. With regard to the programmability—business logic—of CBDC, it states that “hosting business logic also creates a number of reputational risks and potential conflicts.” Consequently, central banks claim that their private vendor partners will manage “business logic.”

Regardless of what platform compliant coins or tokens the public chooses, we will not be able to access them “anonymously.” Consequently, the BoE, in this instance, claims it has farmed out issuance of the necessary, corresponding digital ID to the private sector:

Users would need to be authenticated to carry out CBDC transactions. PIPs would be responsible for authenticating users. This is the Bank’s preferred approach to user authentication as it allocates the responsibility for onboarding [getting you to use CBDC], AML [anti-money laundering] and KYC [know your customer] checks to PIPs, and does not require the Bank [BoE] to store personal data. PIPs would likely need to comply with strong customer authentication (SCA) requirements. This means that users might have to authenticate two or more elements categorised as: knowledge (something you know) — a personal identification number (PIN) or password validated either locally on the device or online; possession (something you have) — in most cases, this would be either the smart device or the smart card; and inherence (something you are) — biometric authentication, such as facial or fingerprint recognition.

But the BoE then contradicts itself:

The Bank may need to collect operational metadata for analysis of system status and performance. This would allow the Bank to maintain the core ledger and the API layer. The Bank could also collect aggregate data, subject to effective anonymisation and privacy protections, in order to undertake economic and policy analysis.

The BoE is intent on harvesting all transaction data, including users’ biometric digital IDs from its “private” partners, while also claiming that it isn’t. This same deception is common to all two-tier models.

The public will only have access to their CBDC-related products and services, i.e., “money”—via PIPs and the ESIPs in the UK—in exchange for their “biometric authentication.” Where the alleged “anonymisation and privacy protections” fit in to the UK’s proposed two-tier model is impossible to determine.

The BoE says that “any information accessed by the Bank [BoE] would have to be effectively anonymised off-ledger.” This is because the “on-ledger” CBDC system it has designed doesn’t leave room for any “anonymisation.”

The BoE claims the “off-ledger” privacy protection will supposedly follow data privacy guidelines stipulated by the UK Information Commissioners Office (ICO). However, the only ICO document it cites merely describes basic data protection principles. The referenced document says nothing about how these principles will be applied to the BoE’s two-tier system. Nor, crucially, does the BoE specify “who” will supposedly “anonymise” the raw biometric digital ID data.

There are potential privacy-enhancing technologies (PETs) that the BoE could utilise, but it has seemingly rejected these in its technical specifications:

PETs are likely to introduce system complexity to varying degrees. This could create a tension with security, performance, resilience, interoperability and extensibility requirements, as well as with system build and operation costs. The Bank does not intend to receive or use personal data. [. . .] Further work is needed to assess the technology implications of such an arrangement.

Contrary to its claims, there is no firm BoE commitment to any «anonymisation and privacy protections.» All the BoE offers are vague promises that some sort of privacy will be maintained by an as-yet-unknown “off-ledger” actor.

The BoE clearly wants to hoover up users’ biometric digital ID and transaction data from the private PIPs and ESIPs. It also clearly intends to use this data for “economic and policy analysis” in order to ensure that the system delivers government and BoE “policy objectives.”

Those objectives are decided neither by the UK government nor the BoE. The policy agenda is set by the G3P regime at the global governance level.

SDG16.9: Vendor Agnostic Digital ID?

Given the international trials and pilots, the regime undoubtedly recognises the public’s apprehension and reluctance to accept government digital ID and to hand over their personal data to central banks. The trick, then, is to construct interoperable monetary and ID systems that gather everyone’s data without alerting “users” to the fact that they have subscribed to the regime’s centralised system.