Key Takeaways (click arrow to expand)

- Intelligence-affiliated venture capital firms dominate the financial technology industry

- Entrepreneurial social groups such as Endeavor, functionally similar to programs like the WEF’s Young Global Leaders (YGL) and the Henry Crown Fellowship, capture innovators at their startups’ incubation

- Endeavor functions like the WEF-YGL program functions for public sector capture, but targets the private sector in emerging markets specifically, while masking their common ties to the likes of Edgar Bronfman Jr. and Pierre Omidyar via its “multiplier effect”, making many emerging market startups appear decentralized when they are in fact funded by the same interests

- These network “mafias” have numerous connections to notorious sex blackmail rings such as those led by Jeffrey Epstein and NXIVM

- Information banking, led by Citi, Visa and PayPal, has led to the creation of information as money – bitcoin and tokenized dollar instruments. PayPal is closely tied to Endeavor

- Many of the early funders of Microsoft, eBay, PayPal and Facebook are also affiliated with bitcoin-bank Xapo. Xapo’s founder and chairman, Wences Casares, owes his commercial success to Endeavor and has maintained close links to the organization

- The bitcoin-dollar system, akin to the petro-dollar system, is explicitly being built by Xapo in terms of custodial solutions, dollar-denominated on/off ramps perpetuating the US Treasury market, and the on-shoring of bitcoin within the US regulatory system

- The proto-bitcoin-dollar architects were all on Xapo’s initial advisory board

- The same players behind the deregulation of the banking sector in the late 1990s, which led to the 2008 crisis and bailouts as well as the restructuring of the Latin American debt from public to private sector banks, are promoting the use of stablecoins to push dollarization on the Global South, specifically Latin America

Before the turn of the millennium, the old adage on Wall Street was “it’s not what you know, it’s who you know.” This same sentiment has been exhibited and exemplified across nearly all industries, and within both the private and public sectors, whether through corporate nepotism and genetic lineage, or even more sinister means such as blackmail and power-driven coercion.

As new technological advances began to become a major part of the American economy and culture, prominent figures within the CIA decided that the “information revolution” necessitated that the Agency “forge new partnerships with the private sector,” specifically what would later become the biggest names in Silicon Valley. The end result of this pivot, the CIA’s very own venture capital arm In-Q-tel, would later back a constellation of what are now powerful technology companies, while some of the wealthiest Silicon Valley CEOs would work to supercharge, in different yet complementary ways, the public-private fusion of US intelligence and tech companies critical to the global economy. As one US intelligence adviser told FOX Business regarding In-Q-tel, “If you want to keep up with Silicon Valley, you need to become part of Silicon Valley.”

While not the direct focus of this piece, the spin off of the US intelligence community into the world of venture capital, with other nation’s intelligence agencies later following their example, is but a signpost for the post-Y2K entanglement of the private and public sectors, and perhaps more importantly, the understanding of how the modern perception of the masses is no longer best influenced by capital control alone, but by controlling particular people themselves, creating powerful networks and markets of influence backed by human capital itself.

In the world of soft money, freely printed fiat, and exponential monetary debasement, the role of the venture capital firm has gone from seeking meager yield from the revenues of so-called Unicorns, to influencing the people behind the companies themselves, shaping entrepreneurs into perhaps unwitting but nevertheless useful agents of larger global agendas.

Data is the most sold commodity in the world, and the modern private sector –– led in no small part by the US’ Silicon Valley –– has seemingly become more about acquiring user data to sell rather than direct profits from business themselves. Social media, dominated by the likes of Facebook, X/Twitter, LinkedIn, Instagram and YouTube, has become the new frontier of venture capital, despite generally zero direct revenue inflow coming from the websites or app users themselves. These private-in-name-only companies (PINOCs) often feed on large government paychecks, including through subsidies of modern advertising budgets spent to purchase views from their large user-bases, or through initial seed-funding and technological development from former government employees. While spending most of the day hiding behind oft-unread user agreements that restrict user content –– often speech –– or sell user data –– whether for commercial or national security applications, these PINOCs grow fat off of government contracts, amassing formidable, too-big-to-fail status as platforms within the “free” marketplace of ideas.

While the focus of this piece isn’t simply the notion that Big Tech has largely and successfully sought control over users and their data, but rather a less discussed public sector coup from organizations within Wall Street and Silicon Valley that have slowly bought influence over the mover and shakers of the modern economy, as the digitalization of money leads to the globalization of markets. The oncoming maturation from the synthesis of the economy and the internet into an internet-based economy is no accident, and those in control of the services, issuers and providers of the means for such an economy have been quietly groomed for at least three decades by many of the same faces and firms behind the first dot com bubble. These days, power isn’t derived from “what you know,” or even “who you know,” but from who you own.

Priming The Americas: The Founding of Endeavor

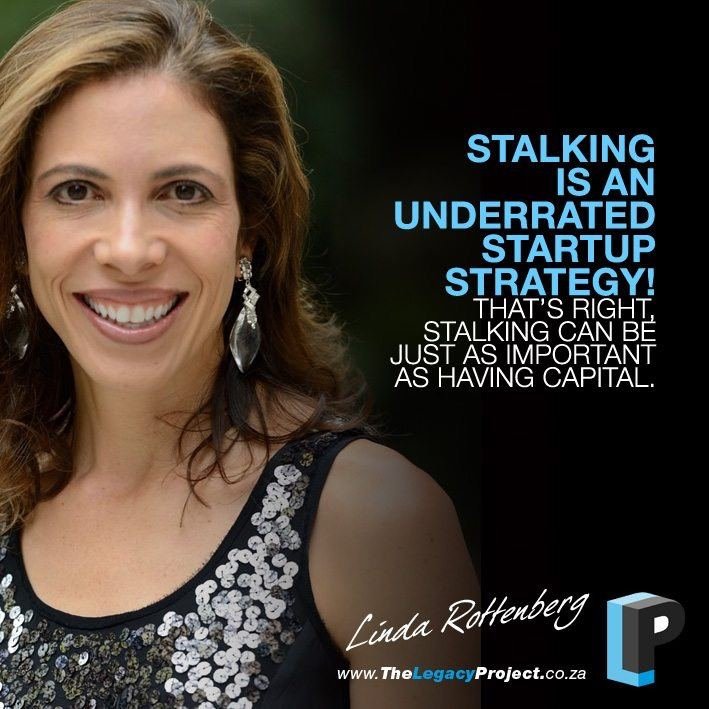

Endeavor is a non-profit organization founded in 1997 by Linda Rottenberg and Peter Kellner to “build thriving entrepreneurial ecosystems in emerging and underserved markets around the world.” Marketing itself as the “leading global community of, by, and for High-Impact Entrepreneurs,” Endeavor aims to “change communities and countries” by supporting entrepreneurship “where it is needed most.” According to their website, over 2500 Endeavor Entrepreneurs have been selected, leading to more than $67 billion in revenue generated and over 4 million jobs created, not to mention the $500 million in assets held by their venture firm, Endeavor Catalyst, and more than 600 team members in 42 markets across the globe. In order to “sustain Endeavor’s long-term operations in a mission-aligned way,” Endeavor launched Endeavor Catalyst as a “rules-based, co-investment fund” that is set up to invest in “the same High-Impact Entrepreneurs that Endeavor Global supports,” placing Endeavor Catalyst amongst the “world’s top early-stage funders of startups-turned +$1 billion companies” focusing on markets “outside of the U.S. and China.”

At a discussion hosted by Goldman Sachs in 2014, Rottenberg described the impetus for the founding of Endeavor: “In the mid-1990s, there wasn’t really a word for ‘entrepreneurship’ in Spanish or Portuguese or Arabic or Turkish. Now they all exist, but 20 years ago they really didn’t as words or as concepts.” Rottenberg, a Yale Law School graduate, met her eventual co-founder Peter Kellner on a recruiting trip to Harvard Business School while working in Argentina for Bill Drayton’s non-profit Ashoka, known for pioneering “venture philanthropy” through “small cash infusions to local groups.” Ashoka set the standard in development work, and their concept of microfinance is used “all over the world to help add to the ranks of the world’s entrepreneurs.” Drayton was also a mentor to Kellner and many others within the social entrepreneurship space, having invented the term in 1972.

Much of the significant moves in the so-called “citizen sector” can be directly attributed to Drayton, who made it “his life’s work to not only expand Ashoka” but to “develop the field as a whole.” While at Harvard, he founded Ashoka table, where students sat alongside “government and industry leaders” to ask about “how the world really works.” Drayton moved on to Oxford as a Rhodes scholar and eventually graduated from Yale Law School. At 21 years old, Drayton volunteered on the 1964 House campaign of former Indiana Congressman Lee Hamilton, who is perhaps most famous for eventually co-chairing the 9/11 commission. He then spent 10 years at the consulting firm McKinsey & Co., where he got an insider’s education on public policy and industries, eventually creating the nation’s first nicotine tar tax while advising New York City. As an assistant administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for the Carter administration, Drayton pioneered the concept of emissions trading, in which “companies or whole countries” are able to “reduce their allotment of pollution emissions” via the free-market by “selling those allotments to others.” Later on during the Reagan administration, Drayton successfully “used the media” to stop Reagan from dismantling the EPA.

While describing the impact of his company, Drayton was quoted as saying “within five years, more than 50 percent of Ashoka fellows change national policy in their respective countries.” Drayton recognized that government was often lacking efficiency while the private sector pursues profit, and thus “the nonprofit sector was ripe to provide change.” The third sector, or as Drayton calls it, the citizen sector, has seen immense growth with “70 percent of registered nonprofit groups” in the United States “under 30 years old.” “More and more people want to do this kind of work,” explained Drayton. “We are creating the jobs; the salaries are going up. We are desperate for managers.”

While at Princeton, Kellner met Drayton, and recalls leaving their first meeting thinking, ‘I am going to attach myself to this guy for the rest of my life.” Kellner calls him his “hero, mentor and close friend.” Kellner is also the founder of Richmond Global Ventures, which made its first investment in 1995 in Gary Mueller’s Internet Securities while Kellner was still studying at Harvard Business School. This would later become a formative part of the Endeavor network, as Mueller quickly became a founding board member of Endeavor, having been “the first person to put financial securities in emerging markets online,” an idea deemed “brilliant” by Kellner.

After “taking a leave” from Harvard Business School to attend Yale Law School before eventually finishing both degrees, Kellner traveled with Drayton to Latin America to take part in the Ashoka selection panels, where Drayton’s organization vetted and selected the entrepreneurs to support. It was here that he first connected with Rottenberg, and they quickly got to discussing their vision for the global economy. “We had all these theories of entrepreneurship and said, ‘Let’s see if we can find the Steve Jobs of the emerging world’,” Kellner remarked. Borrowing heavily from the Ashoka model, Kellner and Rottenberg birthed their Endeavor business plan in 1996 and founded the company the following year. Rottenberg still leads Endeavor Global as its CEO, and while Kellner has remained on the board and continues to be one of the nonprofit’s large benefactors, he “never took a check from Endeavor.”

«There was talent, but there was no trust,» Rottenberg told USA Today. «You were either getting micro-loans or were friends with one of the 10 most powerful families in the country and getting funding. There was nothing in between.» Rottenberg’s Endeavor Global aimed to fill this gap in the “citizen sector” within the emerging markets of the world, leading to Endeavor being “mistaken for a cult” along their way in helping “entrepreneurs ramp up” to become “global players.” Through her decades of work in the field, Rottenberg has earned the title “the entrepreneur whisperer,” “Ms. Davos,” and “la chica loca,” with political pundit and government advisor Thomas Friedman naming her the world’s «mentor capitalist.” Rottenberg serves on the Zayo Group board, a global provider of bandwidth infrastructure, and is a member of the Inter-American Dialogue, Council on Foreign Relations, and Young Presidents Organization (YPO), while also sitting on the entrepreneurship steering committee of the World Economic Forum. In 2002, the Schwab Foundation and the WEF endorsed Endeavor as “one of 40 leading examples of social entrepreneurship worldwide.” The seed capital for Endeavor was provided by Stephan Schmidheiny, a Swiss industrialist whose family and fortune are deeply tied to those of outgoing WEF chairman Klaus Schwab and who has donated a large amount of his personal fortune to Latin America over the years. Aside from Schmidheiny, another $10 million in funding came from Pierre Omidyar’s Omidyar Network, the eponymous philanthropic organization headed by the eBay founder.

In a 2013 interview, Rottenberg described Endeavor as “bringing the magic of Silicon Valley to emerging markets.” Her association with Big Tech stalwarts should come as no surprise, including Omidyar and PayPal/LinkedIn’s Reid Hoffman (Hoffman later suggested the founding of Endeavor’s investment firm Endeavor Catalyst). Yet, it was the partnership with eventual Endeavor Board Chair and Seagram’s heir, Edgar Bronfman, Jr., that elevated the company to the powerhouse it is today. Rottenberg met Bronfman in 2004, and he immediately set lofty goals for the relatively young company. «He said, ‘Linda, Endeavor is charming, but I want it to be important. You should aim to be in 25 countries by 2015.’ I fell off my chair then. But now, we’re almost there.»

“If I look at the phases [of Endeavor], they’ve all been about the people,” explained Rottenberg. “Phase one—roughly 1998 to 2003—was about getting top, local business leaders to pick us up…Phase two began in January 2004, when Edgar Bronfman, Jr. became our board chair.” His addition was later described by Rottenberg as taking Endeavor “from being a founding board” into nurturing a board that “had a focus on resources and strategy at its core.” At the time, Bronfman was best known for being the CEO of Warner Music, a member of the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), a member of the National Advisory Board at J.P. Morgan Chase, and for having previously taken over the Seagram’s empire in 1994 upon the retirement of his father, Edgar Bronfman, Senior.

Bronfman, too, spoke highly of Rottenberg, claiming that «ultimately, I think her model is the model for true economic development. Micro-financing helps alleviate poverty, but the real game changer is growth in the medium sector, with companies that grow themselves and then give back.» Echoing Rottenberg’s comments on the world economy’s influence on world languages, Bronfman told the attending members of the Endeavor Global 2009 Gala:

“When Peter and Linda started Endeavor, and actually up until a few years ago, there was no word in the Spanish or Portuguese languages for entrepreneur. The word simply didn’t exist. So imagine how alien to the culture entrepreneurship is in those communities. It was so interesting to have one of our board members from Chile yesterday say that there’s a presidential election happening in Chile, and for all three candidates that are running, entrepreneurship is the core of their presidential economic growth platforms. It’s extraordinary what’s happened and really it is due to Endeavor.”

– Edgar Bronfman, Jr., 2009

While the new addition to the Spanish language is noteworthy, it is perhaps the acknowledgement of the private sector’s influence on the public sector within Chile, wherein all three of the presidential candidates are pushing to promote the entrepreneurial movement, that is more telling of Endeavor’s impact on Latin America and emerging markets at large. It was only one year earlier, in 2008, that Endeavor had received a $10 million dollar commitment from the Omidyar Network, in which the press release notes that Endeavor entrepreneurs are “jumpstarting private sector development in their countries.” “Endeavor believes that in Omidyar Network, we have found a partner that understands high-impact entrepreneurship is an integral part of economic and social development in emerging economies,” Rottenberg states. “This grant will enable Endeavor’s model to build the conditions for the next Silicon Valleys to spring forth in emerging economies.” The Omidyar Network intended to support Endeavor so it would “reach more emerging-market entrepreneurs” in order to “create more high-value jobs,” and “inject billions into local economies” in both “investments and revenues.”

Phase three, according to Rottenberg, was “when Omidyar Network took a bet on us” and challenged Endeavor to “build in retention” due to “losing smart, young people” to hedge funds and other private equity firms. Much of the capital spent to retain talent within the network came from “seven-figure donations” by the likes of Bronfman, Hoffman, Schmidheiny, Omidyar, and the Dubai-based private equity fund, The Abraaj Group, before the eventual formation of its investment arm, Endeavor Catalyst. Despite being dubbed a “Charity Without The Checks,” a Forbes biography for Rottenberg claims that “Endeavor network members pay $10,000 annually” and “fork over 2% of any liquidity event.”

Another key force behind Endeavor’s growth has been Bain Capital, with Bain Capital Ventures and New York Federal Reserve Fintech Advisory Group member, Matt Harris, becoming a board member. Bain helped with “crafting criteria for the entrepreneur search-and-selection process,” in which final decisions often take place “under the watchful gaze” of notable executives like John Donahoe of eBay, Jack Dorsey of Twitter and Square, and Endeavor board member Reid Hoffman of Greylock Partners. Hoffman is quoted on the Endeavor website as saying «What Endeavor does better than any other organization is to create entire cultures of entrepreneurship that spread within and between countries.» Endeavor Global itself puts it slightly differently:

“That’s why the word “ecosystem” is so often used in the startup world, borrowing from the world of biological systems that interact to create something extraordinary. But if you dig further into the background of the most successful companies, you’ll often find a few individuals that mentored, personally invested in, and inspired these big-thinking founders. At Endeavor, we call these inspirational entrepreneurs “Big Bubbles,” named after the visual depiction of their positive impact laid out over time.

When multiple big bubbles come from a single startup, you often hear the term “mafia” used to describe them (e.g., The Paypal Mafia). Endeavor has seen its own entrepreneurs generate startup mafias around the globe, from Rappi in Latin America, who’ve spawned over 100 startups, to the Careem mafia in the Middle East. We call this paying-it-forward mindset The Multiplier Effect, when an individual reinvests their own entrepreneurial success and multiplies it across many other startups.

As former Endeavor President Fernando Fabre points out in this great TedTalk, these “Big Bubble” entrepreneurs don’t measure success by the size of their wealth or their companies, but by the size of their influence.” (emphasis added)

–– Endeavor Global’s Celebrating The Multiplier Effect

Manufacturing Young Global Leaders for the Global South

Endeavor’s ambitions and function in the private sector, while unique in many ways, is closely aligned with the philanthropic paradigms of the Bronfman family and other ultra-wealthy, organized crime-linked oligarchs tied to the Bronfmans, including Leslie Wexner and the Crown family, as well as now-notorious organizations like the World Economic Forum and lesser known groups like Endeavor. This paradigm involves seeding and developing human capital through philanthropic or “entrepreneurial” organizations they control and/or fund and then using their significant private sector clout to ensure that the “leaders” they have trained up, molded, funded and deeply influence become successful, favoring their acquisition of critical and lucrative contracts and ensuring that their venture capital network allows them to dominate entire industries, particularly in less industrialized nations in the Global South.

Much like the World Economic Forum’s Young Global Leaders program has facilitated the placement of its trained, ideological allies in positions of top political power around the world, groups like Endeavor and their equivalents help ensure that similarly controlled business leaders dominate the private sector and become the public face of emerging market monopolies that are, ultimately, part of a broader network. By ensuring that they dominate the leaders of both the public and private sectors of the current and new generations, these oligarch networks are able to control both sides of the “public-private partnership,” which sits at the very heart of so-called stakeholder capitalism – an economic model promoted heavily by oligarch clans like the Bronfmans, Wall Street titans like Larry Fink and the World Economic Forum, whose chairman Klaus Schwab developed the term.

The Bronfman family, based in Canada for over a century after immigrating there from Eastern Europe, dominated the American liquor trade in the post-Prohibition era. This was, in large part, due to their close connections to organized crime, which facilitated their cross-border liquor business during Prohibition, a policy which forced nearly the entire American liquor industry to collapse (save of course for an organized crime-linked associate of Samuel Bronfman, Lewis Rosenstiel of Schenley Liquors). Seagrams, well after the firm was run by Sam Bronfman’s son Edgar Bronfman Sr., remained tied to organized crime through two company directors – Lew Wasserman and Frank Biondi of MCA, a company that the Bronfmans would later go on to acquire. MCA, especially under Wasserman and Biondi, had long been a mob-tied firm and maintained ties to mob figures as well as intelligence agencies, as detailed in the works of authors Dan Moldea, Cheri Seymour and several others.

Another person closely tied to Seagrams and the Bronfmans was Mayo Shattuck III, formerly of the investment bank Alexander Brown & Sons, later acquired by Bankers Trust and then Deutsche Bank. Mayo Shattuck’s boss at Alexander Brown & Sons, Alvin “Buzzy” Krongard was simultaneously on the CIA payroll. Krongard would later join the CIA directly in 1998, leaving his post at Alexander Brown (then Bankers Trust) to do so. At the agency, Krongard helped create In-Q-tel, develop the CIA’s post-9/11 torture and rendition program, and encourage the modern surveillance state with Silicon Valley’s help (Krongard and Shattuck at Alex Brown, had also helped underwrite some of the Valley’s biggest companies). Krongard was also a “close friend” of George Tenet, CIA director from 1996 to 2004 and Krongard’s boss at the CIA who “specialized in private banking operations serving extremely wealthy clients.” Tenet is now Chairman of Allen & Company, created by organized crime associates Charles and Herbert Allen, and an In-Q-tel board member. Furthermore, both Krongard and Shattuck developed a relationship with Israel intelligence and politicians, helping to influence the development of that country’s tech sector.

In addition, the bank, as well as Shattuck and Krongard, would later become central suspects in the very under-investigated 9/11 insider trading scandal where airline stocks were shorted just before the September 11th attacks. Shattuck, who was then serving as CEO and chairman of Deutsche Bank after its 1999 merger with Alexander Brown/Bankers Trust, abruptly resigned from the bank on September 12, 2001. Shattuck now sits on the board of Bitcoin mining infrastructure company Hut8 (formerly US Bitcoin Corp.), while the chair of the board – Bill Tai – worked under Shattuck and Krongard at Alex Brown & Sons. Shattuck, until 2020, was a long-time board member of Michael Saylor’s Alarm.com. Saylor’s company MicroStrategy, now known as one of the largest holders of bitcoin in the world with 226,331, was seed funded by DuPont in 1989, when Seagrams was a significant owner of the company, with three board members chaired by the Bronfman-backed Edgar S. Woolard, Jr.

With a near monopoly on North American liquor sales for much of the 20th century, the Bronfman family has since used their fortune to develop a network of influence and “philanthropies” with other organized crime-linked billionaires like Leslie Wexner, with whom Charles Bronfman cp-founded the “Mega Group” in 1991. That particular group included not just Wexner and the Bronfman brothers Edgar and Charles, but also other powerful mob-linked families like the Crowns of Chicago, have specifically modeled a significant share of their “philanthropic” spending on developing leaders in both the public and private sectors in order to boost specific policy objectives, especially those dealing with the (drastically one-sided) US-Israel relationship.

The Bronfman and Wexner fellowship, for example, share significant overlap and are deeply connected to Harvard University, which came under fire in recent years for its unusually close relationship with Wexner crony and the notorious, intelligence-linked pedophile Jeffrey Epstein. That relationship notably flourished under the Harvard presidency of former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, who is mentioned several times later in this article. For instance, the Wexner Foundation is responsible for the existence of Harvard Kennedy school’s Center for Public Leadership, which directly collaborates with the World Economic Forum Young Global Leaders program.

Aside from Harvard, the Mega Group philanthropies also greatly influence US public policy. For example, the Wexner Foundation’s programs are deeply tied to the controversial Israel lobby organization, AIPAC. Elliot Brandt, AIPAC’s national managing director, is an alumnus of the Wexner Heritage Program and, in a 2018 speech at that year’s AIPAC policy conference, Brandt noted that “most of the [AIPAC] National Board consists of Wexner Heritage Alumni, not to mention its regional chairs and some of its most committed donors as well.” Meanwhile, Edgar Bronfman made donations to AIPAC “intended to make him the lobby’s largest single donor.” Wexner’s close ties to AIPAC take on a different tone when one considers his close association with the Israeli intelligence-connected Jeffrey Epstein. Epstein notably had significant connections at one point to a Bronfman family insider-trading scandal and the Bronfmans, Edgar Jr.’s sisters Sara and Clare, were at the center of the NXIVM sex cult scandal. AIPAC itself also has long-standing and controversial ties to Israeli intelligence. For instance, AIPAC was at the center of an Israeli espionage scandal in the US in the mid-1980s as well as again in 2004, when a high-ranking Pentagon analyst was caught passing highly classified information over to Israel’s government via top officials at AIPAC. Despite extensive evidence, particularly in the latter case, AIPAC itself avoided charges. As journalist Grant Smith noted at the time, “the Department of Justice’s chief prosecutor on the [AIPAC] espionage case, Paul McNulty, was suddenly and inexplicably promoted within the DOJ after he backed off on criminally indicting AIPAC as a corporation.” The charges against the specific AIPAC officials involved were also dropped.

Then, there is the case of the Crown family, who have long run the major US weapons manufacturer and military contractor, General Dynamics. The Crowns, along with Wexner’s right-hand man after Jeffrey Epstein, John Kessler, helped install Jamie Dimon as the head of BancOne, ensuring Dimon’s J.P. Morgan presidency after its BancOne merger. Edgar Bronfman Jr. sat on J.P. Morgan’s board alongside James S. Crown and Kessler. The Crowns have historic ties to the mob and also allegedly to Israeli espionage efforts to steal US military technology, which even led to Lester Crown losing his national security clearance for a time.

The Crown family’s fellowship is housed at the influential Aspen Institute, a think tank with very close ties to the US National Security state and US intelligence specifically (see here, here, here, here, here and here). Lester and Paula Crown sit on the Institute’s board of trustees and the board is notably chaired by Margot Pritzker, another organized crime-linked Chicago-based family with deep ties to Barack Obama (just like the Crowns) and the Epstein scandal. Other members of Mega Group families, like the Lauder and the Tisch families, are also on the Aspen Institute’s board.

Aspen’s Henry Crown fellowship, named for Lester’s father who built up the family’s fortunes with the Chicago “supermob,” is hugely influential and, according to one fellow – now a VP at Boeing, “the [Henry Crown] fellowship is not something you do. It is something you become.” The fellowship was recently revamped into what is now the Aspen Global Leadership Network. Its alumni include Peter Kellner, co-founder of Endeavor Global who is also a WEF Young Global Leader, as well as other important Endeavor entrepreneurs and board members. Other Endeavor associates now manage key Aspen Institute programs or have other direct ties to the Institute. Kellner, like Edgar Bronfman Jr., also serves on the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), which – according to one former Secretary of State (Hillary Clinton) – is the “mothership” from which the State Department takes its orders. The CFR also came under fire for receiving large donations from Jeffrey Epstein and failing to address his member and donor status even after his now infamous conviction in the mid-2000s. In addition, influential Endeavor-linked Silicon Valley figures like Reid Hoffman and Wences Casares are also both Crown fellows, while Casares, like Kellner, is also a WEF Young Global Leader. Both Hoffman and Casares share significant connections to PayPal.

Hoffman, whose ties to Endeavor are considerable, is another key member of the “PayPal mafia” who is worth discussing in greater detail due to his ties to Jeffrey Epstein. Of all of Epstein’s numerous Silicon Valley connections, Hoffman was one of the closest to the deceased pedophile and intelligence asset. Hoffman initially claimed that his relationship with Epstein was solely related to fundraising for MIT Media Lab and claimed that this is why Hoffman had invited Epstein to a 2015 dinner where he socialized with Silicon Valley oligarchs including Mark Zuckerberg, Peter Thiel and Elon Musk. Business Insider at the time reported that Greylock, where Hoffman is a partner, denied that Epstein “had invested in any [of its] funds as a limited partner,” but that “there remain the possibility, however, that Epstein invested in Greylock and others through a ‘fund of funds,’ which does not have to disclose its investors […]” In addition to Hoffman, another important partner at Greylock is Howard Cox, who serves on the board of the CIA’s In-Q-tel and also on the foundation board of the WEF’s Young Global Leaders program. All founding partners of Greylock, including Cox, received the 2003 HBS Awards for Alumni Achievement, the school’s highest honor, during the Harvard presidential tenure of another Epstein associate, Larry Summers.

However, in 2023, it was revealed that Hoffman had failed to disclose his flights on Epstein’s private plane, his trips to Epstein’s Caribbean island and his overnight stay at Epstein’s New York townhouse, after which Hoffman attended a “breakfast party” along with Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates. Hoffman sits on Microsoft’s board, a position he obtained after selling LinkedIn to Microsoft. Epstein also had significant ties with other members of the “PayPal mafia” like Peter Thiel, who met numerous times with Epstein and whose VC firm Founders Fund co-invested with Epstein in the Israeli intelligence-linked company Carbyne, as well as Elon Musk. In addition, one of PayPal’s earliest backers, Bill Elkus, was once a trustee for one of Epstein’s foundations.

In addition to his controversial Epstein ties, Hoffman’s “philanthropy” is similarly controversial. For instance, he funded “a dark money non-profit” called Acronym, which was behind a nonfunctional voter app that essentially sabotaged the 2020 Iowa Caucus. One of the other leading donors to Acronym is Donald Sussman, the son-in-law of Mega Group member Laurence Tisch with a major presence in the USVI, where his associates were embroiled in a bribery scandal. Sussman, in the USVI, also shared an attorney with Jeffrey Epstein. Regarding Hoffman’s political “activism,” Vanity Fair wrote that “Hoffman and [Dmitri] Mehlhorn [a corporate consultant tied to Hoffman], after all, are not just building a power base that could supplement traditional Democratic organizations, they are, potentially, laying the groundwork to usurp the D.N.C. entirely.” Prior to Acronym, Hoffman had funded Project Birmingham, which ran a covert campaign to depress voter turnout and create the illusion that there was foreign interference in a 2017 Alabama Senate race. Other examples of Hoffman “philanthropy” include kick-starting TechCongress, which has funded the placement of “outside tech staffers in congressional offices” since 2016, where they directly inform Congressional technology policy. Hoffman also donated $4 million alongside Endeavor funder and PayPal owner Pierre Omidyar to fund DoSomething, a non-profit seeking to create “socially conscious leaders committed to achieving real and sustainable impact.” When looked at as a whole, Hoffman’s approach to “philanthropy” does not show an interest in altruism, but rather in influence peddling to the point of undermining key democratic processes and institutions.

Given the “philanthropic” network developed in part by his father, Edgar Bronfman Jr.’s purportedly altruistic interest in Endeavor and helping entrepreneurs in the Global South should be scrutinized. While Edgar Bronfman Sr. and other Mega Group grandees initially focused on molding the opinions of Jewish Americans and specifically Jewish American leadership, it eventually expanded beyond to focus on funding and cultivating human capital in both the public and private sectors. Endeavor, co-founded by a WEF Young Global Leader and Crown fellow, follows a similar model focused specifically on the private sector in emerging markets, whereby the group ensures its chosen “entrepreneurs” are successful by connecting them with funding and private and public sector networks in economic environments where Endeavor entrepreneurs have little meaningful competition, allowing them to – in several cases – build new, de facto monopolies. MercadoLibre, often called Latin America’s “Amazon” and “eBay” equivalent and Endeavor’s first success story, is a perfect example and one that Endeavor has since sought to replicate extensively in Latin America and beyond.

However, even this model is hardly new – ADELA, the Atlantic Community Development Group for Latin America, a now defunct industry group composed of titans of Western industry, pooled their money and funded the Latin American “entrepreneurs” of their choosing, effectively “king-making” the continent’s corporate landscape as well as those who would become its most powerful oligarchs. Notably, ADELA helped spawn the Club of Rome, which was instrumental in the rise of the World Economic Forum to prominence. One could argue that Edgar Bronfman Jr. saw Endeavor as an opportunity to resurrect ADELA’s model but for the benefit of the broader “Mega Group” oligarch network with a focus on both emerging markets and 4th industrial revolution technology companies working in crypto, ecommerce and fintech.

Omidyar’s Network

According to Endeavor’s Linda Rottenberg, the group’s “phase three” began when the philanthropies of Pierre Omidyar gave the group $10 million beginning in 2008, which allowed its “entrepreneurs to generate [more] startup mafias around the globe.” Like Edgar Bronfman Jr., the progenitor of Endeavor’s “phase two,” Omidyar has a litany of unsettling connections that suggest that his interest in Endeavor entrepreneurs, their companies and the emerging markets in which they work, is hardly altruistic.

Omidyar, as the founder of eBay, was a revolutionary force in early and current ecommerce. He subsequently took ownership of PayPal in 2002, linking him closely to the “Paypal mafia” that includes Endeavor-linked Reid Hoffman (who helped handle PayPal’s acquisition by eBay), among others. During this same era (the early 2000s), Omidyar had already developed close ties with US law enforcement, hiring a team of former FBI agents to spy on eBay users and track transactions in 1999. In an interview with Max Blumenthal for MintPress News, journalist and author of Surveillance Valley Yasha Levine stated that:

By the mid-2000s, when Google was still a small company and Facebook barely existed, eBay had built this global private division into a behemoth: 2,000 employees and more than a thousand private investigators, who worked closely with intelligence and law enforcement agencies in every country where it operated — including the United States, Canada, Brazil, Mexico, Malaysia, India, Russia, Czech Republic and Poland. EBay was proud of its close relationship with law enforcement, touting efforts to arrest 1,000 people a year and boasting that it had handed over user data to the NSA and FBI without requiring subpoenas or court orders.”

Levine, in another interview with MintPress News, also stated that: “For the past decade Omidyar has quietly worked to expand eBay’s privatized surveillance-state model beyond online sales and into elections, media, transportation, education, finance, as well as government administration. His vehicle for that: the Omidyar Group, an investment vehicle that bankrolls hundreds of startups, business and non-profits around the world.”

Omidyar, since then, has maintained important ties to the US National Security State and Intelligence, with his philanthropies working alongside admitted and suspected CIA cut-outs like the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) and USAID, respectively. Both groups have been used by American empire to conduct regime change operations and “color revolutions” globally and Omidyar has been the subject of several reports detailing Omidyar’s role alongside USAID et al. in the 2014 regime change in Ukraine, which helped lay the groundwork for the current Russo-Ukrainian conflict, and also the Syrian conflict.

Omidyar’s “philanthropy” was largely under the radar until his 2013 decision to finance and help create the media outlet The Intercept received widespread media attention. The Intercept’s founding was directly related to the documents provided to Glenn Greenwald and others by former Booz Allen Hamilton employee Edward Snowden. Omidyar’s decision to support the outlet was very out of character, despite the glowing press coverage, given that he – just a few years prior – had referred to those like Snowden (i.e. whistleblowers) as “thieves” and argued that leaked documents should never be published. Also odd is the fact that, shortly before Omidyar approached Greenwald about funding The Intercept, Greenwald had been a key focus of an effort led by Palantir, an intelligence contractor co-founded by PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel and which had originally began at PayPal, to neuter “the WikiLeaks threat.”

After the creation of The Intercept, critics argued that the Snowden leaks had been “privatized”. Time has since proven those critics largely right, as the outlet quietly yet permanently closed its Snowden archive in 2019, leaving about 90% of the cache forever unpublished, effectively burying the vast majority of the Snowden documents. The allegation was made years prior that Omidyar’s motive in “privatizing” the leaks was due to unpublished Snowden documents containing “compromising information about PayPal (owned by Omidyar) and its dealings with the US government and intelligence community.” In addition, other whistleblowers who leaked documents to The Intercept – which used Snowden and Greenwald to advertise itself as being “safe” for such individuals – were subsequently imprisoned after reporters working for The Intercept failed to protect them and – in at least one case – doxxed them directly to the government.

As a result, some critics have posited that Omidyar may have created The Intercept with the intention of using it as a whistleblower honeypot in order to, as Omidyar once said himself, “catch the thie[ves].” This is supported by other actions taken by Omidyar after The Intercept’s creation, such as Omidyar’s decision to make Snowden’s former boss at Booz Allen Hamilton, Bob Lietzke, an Omidyar fellow two years after Snowden blew the whistle. In addition, during this same period when Omidyar was both helping create The Intercept and funding groups in Ukraine alongside USAID, Omidyar made more visits to the Obama White House than any other Silicon Valley figure, suggesting that – of all the Silicon Valley oligarchs – he was the closest to that particular administration at the time.

Omidyar was also heavily involved with the Tibetan monk Tenzin Dhonden, flying him around on his private jet and coordinating meetings with the Dalai Lama, who Omidyar professes to intensively follow (for information on the Dalai Lama’s ties to the CIA, see here). During this same period of time, Tenzin Dhonden reportedly became sexually involved with Sara Bronfman, the sister of Edgar Jr., and connected to the aforementioned NXIVM sex cult. Tenzin Dhonden later coordinated a secret deal for the Dalai Lama to endorse NXIVM’s now imprisoned leader Keith Rainere. Notably, representatives of both the Omidyar Network and NXIVM were both listed as members of the Clinton Global Initiative in 2007, with Omidyar giving $30 million to the Clinton-led organization (which was also allegedly the brainchild of Jeffrey Epstein). NXIVM’s representative at the CGI was Clare Bronfman, while her sister Sara and her father Edgar Sr. were also members. NXIVM and Omidyar also share ties with billionaire Richard Branson, who hosted “wild parties” and a conference for NXIVM on his private Caribbean island and, around the same time, created Enterprise Zimbabwe with Omidyar’s wife Pam. The shared connections between the Bronfman-linked NXIVM and Omidyar appears to add important context to Omidyar’s decision to invest in the Bronfman-chaired Endeavor Global.

Journalists Alex Rubenstein and Max Blumenthal, writing for MintPress News, also noted in their 2019 investigation of Omidyar that the eBay founder had put $10 million into the Maui Land and Pineapple Company, which – by 2010 – became central to one of the largest human trafficking cases in the US for having subjected its migrant employees to “modern-day slavery.” Omidyar acknowledged later learning of the charges in 2008 and then, oddly, chose to expand his relationship with the embattled company in 2010.

Shortly after making his massive commitment to Endeavor, Omidyar’s philanthropies also gave millions to the microfinance platform Kiva in 2010. Many of Kiva’s top executives and co-founders hail from PayPal, others from eBay or the Omidyar Network, and it has been formally partnered with the Omidyar-owned PayPal for years. Its board members have included Endeavor-connected figures like Reid Hoffman (who remains on its board) and Wences Casares, the founder of Xapo, Silicon Valley’s “patient zero” for Bitcoin and a former Endeavor and PayPal board member whose own commercial success is largely thanks to Endeavor. Before Omidyar gave millions to Kiva, it was the subject of critical reporting over transparency problems and the revelation that its promise of direct peer-to-peer lending was “an illusion,” as Kiva lenders “were actually backstopping microfinance institutions” and not actually directly connecting would-be funders to entrepreneurs in emerging markets. It was subsequently reported that Kiva was allowing investors, Google among them, to also invest in those same microfinance institutions “and receive a financial return.”

Kiva has long promoted itself as helping to finance the so-called “unbanked.” However, as time has gone on and since Kiva launched its Kiva protocol, it has become clear that the goal is to yoke the “unbanked” to biometric digital IDs interfaced with digital payment systems. In Sierra Leone, Kiva – in partnership with the United Nations – launched a national digital ID platform on blockchain for the country that also functions as a credit history tracker and their gateway to digital financial services. The program is allegedly yet another opportunity for Kiva “to leverage blockchain for the unbanked.” In addition, other Omidyar-funded groups like Co-Develop, work directly with the UN, the Rockefeller Foundation and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation on efforts to impose biometric digital ID globally, with a focus on the Global South. Also notable in this context is Omidyar’s support of the UN-sponsored Better than Cash Alliance that seeks to accelerate the “transition from cash to responsible digital payments to help achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.”

Pierre Omidyar was also a member of the Berggruen Institute’s 21st Century Council which was active until 2019 and was composed of “former heads of state or government, global thinkers, and tech entrepreneurs” seeking to “help shape the agenda for the annual G-20 summits.” While the council’s political leaders included top advisors to China’s Xi Jiping and a former Mexican president, most of its tech entrepreneurs – save for ex-Google head Eric Schmidt and Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey – made much of their fortunes from eBay or PayPal, including Omidyar himself, Jeff Skoll, Elon Musk, and Reid Hoffman. The council’s goal was to “harness globalization” and make it more “inclusive” in the “wake of the anti-globalization backlash.”

The Endeavor «Mafia»: Globant, MercadoLibre, and Patagon

Having been founded with Latin America as its initial emerging market of choice, Endeavor’s influence on the continent’s private sector has become hugely significant over the past two decades. A network of Endeavor’s biggest successes now dominate the infrastructure for and products of the 4th industrial revolution on the continent. The most dominant of all is MercadoLibre.

Founded by Endeavor entrepreneur Marcos Galperín, MercadoLibre is considered the first Endeavor success story, and Galperín sits on the board of Endeavor’s Argentina branch alongside controversial Argentinian oligarchs, like former George Soros protégé Eduardo Elzstain. Galperín co-founded the company while in the US at Stanford and, two years after being selected by Endeavor, Endeavor helped negotiate a deal where eBay took a major stake in MercadoLibre, owning roughly one-fifth of the company. Also courtesy of the Endeavor network, Galperín’s MercadoLibre has become deeply interconnected with PayPal. MercadoLibre is also a major investor in Paxos, the stablecoin issuer of PayPal’s stablecoin, PYUSD. MercadoLibre’s MercadoPago subsidiary, Ripio (an Endeavor company) and Brazil’s Mercado Bitcoin (another Endeavor/MercadoLibre-connected company) collectively dominate the cryptocurrency industry in South America, particularly its two largest markets – Argentina and Brazil.

In November 1999, the same year Marcos Galperín was chosen by Endeavor, MercadoLibre received $7.6 million in seed funding from Chase Capital Partners and Flatiron Partners. Fred Wilson’s Flatiron had capitalized just three years prior in 1996 for $150 million with funds from Softbank and Chase Capital Partners. Wilson and Flatiron would later go on to fund another notable Endeavor success, Patagon, after being introduced to its creator Wences Casares by Rottenberg. Endeavor had organized “a road show” for Patagon in September 1998 to put Casares and his website at the feet of “potential investors in New York, Boston and San Francisco.” Seven months later, Patagon received its first round of venture financing. Casares later sold Patagon to banking giant Santander, later going on to make several other companies, including Xapo.

Another early Endeavor company is Globant. Globant is a software development, digital infrastructure management and consultancy firm founded in Buenos Aires, Argentina with the vision of “delivering profound transformations for organizations.” These “transformations,” according to co-founder and CEO/Chairman Martín Migoya, involve preparing their customers to “be ready for a digital and cognitive future” and help meet the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. The bulk of Globant-led “transformations” are delivered through AI products, specifically generative AI. Their clients today include Disney (their largest customer), Google, Electronic Arts, Nestle, American Express and Santander Bank. Globant signed their first contract with Google in 2006, a year after becoming an Endeavor entrepreneur company. The company also received an award from the David Rockefeller-founded Council of the Americas (both Galperín and Endeavor Argentina’s Eduardo Elzstain are members) for becoming one of the dominant players in Latin America’s IT industry and “pioneering a new era for innovation and business transformation.” A top Globant executive is a director of Council of the Americas alongside Latin America-focused executives of J.P. Morgan, Citi, BlackRock, Estee Lauder, BNY Mellon, Microsoft, HSBC and Merck, while Elzstain and his long-time associate and fellow Soros protégé Marcelo Mindlin serve on its International Advisory Council.

Globant plays a crucial role in leading its clients, including both companies and public sector agencies, into making AI and emerging 4IR technologies cornerstones of their business and their products/services. They also lead clients to use the 4IR services and products of specific companies, including Microsoft, where Endeavor board member Reid Hoffman also sits on the board. Others on the board include MercadoLibre’s Marcos Galperin, who – along with the Globant co-founders – has been labeled a leader of Argentina’s “new establishment.” Endeavor’s Linda Rottenberg sits on Globant’s board and Reid Hoffman also served on its board for several years. Hoffman also chairs Endeavor Catalyst, which has funded Globant. Globant’s board also includes two former top J.P. Morgan executives, one of whom – Alejandro Aguzin – also sits on MercadoLibre’s board, as well as Andrew McLaughlin, former deputy Chief Technology Officer of the United States under Obama who now also serves on the board of the Ethereum-focused Starknet Foundation.

A significant amount of Endeavor’s clout in Latin America is headquartered in Argentina, exemplified by its powerful, Argentinian branch. The board of Endeavor Argentina includes two Globant co-founders, MercadoLibre’s Marcos Galperin, and Eduardo Elzstain, the Argentinian oligarch with massive holdings in both Argentina and Israel who owes his career to the controversial Hungarian-American billionaire George Soros. Endeavor Argentina is also funded by Elzstain and his company IRSA as well as Argentina’s Banco Hipotecario, where Elzstain is the largest private shareholder, are partnered with the group. Elzstain was also a long-time, close associate of Edgar Bronfman Sr., partnering with Bronfman on university-focused initiatives and serving on the governing board of the World Jewish Congress (WJC), which Bronfman led for decades. According to his bio on the WJC website, Elzstain served as “an unofficial ambassador for Argentina during the economic crisis, working with the World Jewish Congress in attempting to raise the issue of Argentinean economic reconstruction in international economic and financial institutions” like the International Monetary Fund.

Elzstain, who dominates Argentina’s real estate industry and whose close associates dominate its energy sector, is the host of Argentina’s Bilderberg-style, closed-door meeting of public and private sector powerbrokers, known as the Llao Llao Forum (Foro Llao Llao). This year, the main guest was Argentina’s president Javier Milei, who embraced Globant co-founder Guibert Englebienne, Marcos Galperin and Eduardo Elzstain after his speech. The main topics of the secretive forum included cryptocurrency, Artificial intelligence, and “Gen Z.” The cryptocurrency discussions at the conference were led by Sebastián Serrano, an Endeavor entrepreneur whose company Ripio is partnered with Endeavor-backed MercadoLibre, and Rodrigo Benzaquen, former director of R&D for MercadoLibre who now works for the Uruguayan bitcoin start-up Moneero. Between stints at MercadoLibre, Benzaquen worked for Kaszek Ventures, which was created by two Endeavor entrepreneurs, one of whom sits on Endeavor Global’s board. Also present at the Forum was Andy Freire, a funder of Endeavor Argentina, as well as Endeavor Global board member Nicolas Szekasy, among others.

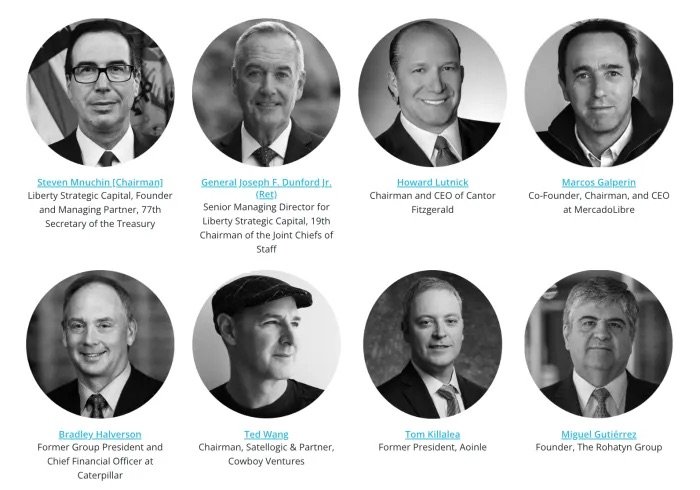

Another speaker was Endeavor entrepreneur Emiliano Kargeiman, a former DARPA, NSA and DHS contractor who co-founded the satellite company Satellogic. As noted in a previous article, Satellogic is part of a network of companies and non-profits working to impose a blockchain-based carbon market on Latin America using satellite surveillance. Satellogic’s board is currently chaired by Trump’s former Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin and its members include chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff under Trump Joe Dunford, MercadoLibre’s Marcos Galperin, and Howard Lutnick of Cantor Fitzgerald. Cantor Fitzgerald is one of the private sector’s main players in the U.S. Treasury system and also manages money for Tether (USDT), a dollar stablecoin largely backed by Treasuries. Lutnick, who purchased the home neighboring Jeffrey Epstein’s townhouse in New York from a Bronfman family trust for “$10 and other valuable consideration,” has publicly promoted Tether on several occasions. Tether had a very close relationship with the defunct crypto exchange FTX and its hedge fund Alameda Research. Tether also recently invested $30 million in Satellogic this April via their investment arm, Tether Investments Limited.

Tether’s co-founders include Brock Pierce, a former Disney child star who figured prominently in the Digital Entertainment Network child sex abuse scandal, and William Quigley, who – along with Bill Elkus – provided the earliest funding for PayPal. As noted previously, Elkus had been a trustee of one of Jeffrey Epstein’s foundation and Pierce was also a visitor to his USVI island. Pierce, who sat on the board of the Bitcoin Foundation, claims that his interactions with Epstein had all “related to cryptocurrency.” Epstein expressed enthusiasm about crypto, specifically the prospects of bitcoin. In 2017, he described bitcoin as “bursting with potential” and promoted its “formal implementation” into the financial system. His views on other digital currencies remain unknown, but he quite possibly influenced the decision made by Joi Ito, the former head of MIT Media Lab who was very, very close to Epstein, to start the influential Digital Currency Initiative (DCI).

Epstein was a currency trader and, according to the Wall Street Journal, claimed to be working for the US Treasury Department on cryptocurrency-related matters. This is not as unlikely as some would think, as Epstein was extremely close to one former U.S. Treasury Secretary, Larry Summers. Epstein had also visited the White House during the Clinton administration at least 17 times and, in 1995, was the subject of discussion between Clinton and one of his top donors, Lynn Forester de Rothschild, in connection with “currency stabilization.” At the time, the destabilization of the Mexican peso was the focus of the administration, particularly of the Treasury Department then led by Robert Rubin and his deputy Larry Summers. The Mexican peso was shorted by currency trader Joe Lewis who had previously shorted the British pound with George Soros a few years prior. Lewis, according to the New York Times, was part of a group of predatory currency traders that also included James “Jimmy” Goldsmith, who first introduced Epstein to elite circles in New York in the early 1970s. Lewis was recently pled guilty to insider trading (no prison time) and had several connection to FTX, including to Sam Bankman-Fried, as well as the chairman of the Bahamian bank associated with both FTX and Tether, Deltec. Lewis is also a business associate of Marcelo Mindlin, the former long-time associate of Eduardo Elzstain and former Soros protégé, in Argentina’s Pampa Energia.

X Marks The Spot: The Bitcoin-bank Xapo

Reid Hoffman: So how did you encounter Endeavor?

Wences Casares [Xapo founder]: I had been trying to raise money for my company for a year and a half and I had had 33 meetings. I kept very detailed notes about each meeting. I would meet with anyone who had any capital. It was hard for me to get those meetings…

We were in this tiny little office there [in Silicon Valley] which was a loaner from a friend and trying to get these things started. We haven’t raised any money, we were behind with our payroll because, well, anyway it was not a good time…and the bell rings and I open and there’s Linda [Rottenberg] and she tells me that she’s heard our names from Andy Freire and Santiago Bilinkis and that she started a nonprofit in New York to help entrepreneurs in emerging markets and that she’d like to see if they can help me.

I remember thinking that this is too strange. I really thought these Mormons are getting more and more creative, you know? I’ve been trying to reach out without any success…it sounded too good to be true. And then I said ‘do you provide money?’ when we were still at the door and she said ‘No, we don’t provide money but we help you in other ways’ and I said ‘Whatever, I have nothing to lose, come on in’ and she changed my life. I wouldn’t be sitting here with you if it weren’t for Linda and for Endeavor.”

– Argentina Entrepreneurship, Endeavor, and Global Lessons w/ Wences Casares and Reid Hoffman on Greylock’s Greymatter Podcast

Wenceslao “Wences” Casares founded the Bitcoin-bank Xapo back in March 2014, only a few weeks after the infamous collapse of the most prominent Bitcoin exchange at the time, Mt. Gox. Casares had had his first success in launching the premier internet service provider in Argentina in the mid-1990s, before making a name for himself with his company Patagon, one of the first Endeavor companies. Casares later sold Patagon to Santander for $750 million before focusing his career on bitcoin after a chance encounter with the digital currency in 2011.

Xapo offers a bitcoin wallet integrated with a secure cold storage vault for transfers with physical servers located globally, featuring biometric access, continuous monitoring, and stringent security protocols. “Every part of their DNA is geared to security,” said Sean Clark, First Block’s founder, who noted that the Xapo vault’s fingerprint scanners “were equipped with a pulse reader” in order to “prevent amputated hands from being used.” Xapo even partnered with Endeavor-backed Satellogic to experiment with taking Bitcoin security in to space. In an interview with CoinDesk in 2015, Casares stated “A lot of the people who have large amounts of bitcoin, that’s what they care about most – security. Nothing is more important to security than keeping private keys offline. We’ve seen the problems of that recently, you can keep them offline but when you bring them online, that’s when compromises happen.” The problems alluded to by Casares are perhaps referencing the fortuitous timing of Xapo’s debut when heightened security concerns from Bitcoiners were exacerbated by the aforementioned collapse of Mt. Gox in 2014. This event resulted in over $450 million in losses for an estimated 750,000 customers after the exchange ceased operations while declaring bankruptcy.

The concept for Xapo, however, originated in early 2011 when Casares purchased his initial bitcoin at approximately $3 each. As his holdings appreciated, he sought a secure storage solution, leading to the development of a personal vault. While colloquially known as the «Patient Zero» of Bitcoin in Silicon Valley, former PayPal board member Casares himself held the keys to a publicly-linked Bitcoin wallet that has transacted nearly 1 million bitcoin –– a staggering number for a single web wallet. Casares’s successful track record in the tech industry, highlighted by Lemon — a digital wallet acquired by LifeLock for approximately $43 million a year before founding Xapo — bolstered Silicon Valley’s confidence in both Casares and his new venture. However, it was this early exposure to vast sums of bitcoin that led Casares personally, and later Xapo, to develop a new industry standard of robust security measures for keeping private keys secure, leading to Xapo’s nickname as the «Fort Knox» of bitcoin. Subsequently, inquiries from friends and financial institutions prompted Casares to expand his self-service into what would later become Xapo. Over the past decade, Xapo has safeguarded bitcoin for “family offices, sovereign wealth funds, and hedge funds,” with a significant client base based primarily in the United States.

Xapo, initially incorporated in Palo Alto, California before moving jurisdictions to Gibraltar, secured an initial Series A worth $20 million in funding on March 2, 2014, led by Benchmark Capital, with participation from Ribbit Capital and Fortress Investment Group, including additional investment from Barry Silbert’s Digital Currency Group, Ben Davenport of Blockchain Capital, Pantera Capital, and Slow Ventures. Xapo conducted a second Series A, which closed on August 15, 2014, worth another $20 million, led by Greylock Partners’s Reid Hoffman and Mike Volpi’s Index Ventures, with participation from Emergence Capital Partners, Endeavor Catalyst and Kauffman Fellow Allen Taylor, Ribbit Capital Managing Partner Meyer Malka, PayPal co-founder Max Levchin, then-head of PayPal David Marcus, the VC firm of the Gemini Exchange co-founders Winklevoss Capital, DST’s Yuri Milner, and Yahoo! co-founder Jerry Yang.

Matt Cohler, a partner at Benchmark Capital –– most known for their early investment in eBay in 1997 –– and founding member of both Facebook and LinkedIn, endorsed Casares’ company by joining the second iteration of Xapo’s board, alongside Ribbit Capital Managing Partner Meyer Malka, and Reid Hoffman. Benchmark was founded by Bob Kagle, a former employee at Technology Venture Investors, notable for being the sole seed investor of Microsoft in 1981. Microsoft and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation would go on to become major donors to Endeavor. At the time it became the sole seed investor of eBay, Kagle’s Benchmark was advised by Burton McMurty, also of Technology Venture Investors.

While the Xapo boards’ connections to PayPal, Microsoft, and eBay are notable, it was the initial Xapo advisory board that raised eyebrows across the financial world back when Bitcoin was anything but the household name it is today. On May 26, 2015, Casares published an entry to the Xapo blog announcing the formation of a new advisory board composed of Visa founder Dee Hock, former Citibank CEO and Chairman John Reed, and the former Treasury Secretary and President Emeritus of Harvard University Lawrence H. Summers.

The Xapo Advisory Board: Dee Hock

The first two members of Xapo’s 2015 advisory board, Dee Hock and John Reed, are notable for their role in leading what are now financial behemoths through their ascendancy and for their early views on banking, information technology and data. Dee Hock, as the founder of Visa, was “responsible for effectively creating payment systems as we know them today,” according to Casares.

The beginnings of Visa lie in the origins of Bank of America’s BankAmericard project. In September 1958, Bank of America, then the largest bank in the nation with $5 billion under management, mailed 65,000 “unsolicited cards to households in Fresno” with the name BankAmericard “emblazoned across the front.” Interestingly, a six-year veteran of the US State Department and the CIA, Ralph F. Young, who would later be named a Vice President at the bank, was the manager of the Fresno area BofA branch during the execution of what the bank later referred to as “The Drop.” Over the next 13 months, BofA issued 2 million BankAmericards with over 20,000 merchants signing up for the program. However, fraud was rampant and within 15 months of launch, the BankAmericard system had officially lost $8.8 million dollars, with actual losses estimated around $20 million. By May 1961, the system finally began generating profit.

In June 1970, after “two years of brainstorming, planning, arguing, and consensus building,” the BankAmericard system passed control to a new independent entity titled National BankAmericard, Inc., which would later become Visa International. Hock was the first CEO of this “nonstock, for-profit membership corporation” in which ownership came in “the form of nontransferable rights of participation.” The new CEO had designed the organization to fit the values of his philosophy, self-described as “highly decentralized and highly collaborative” while pursuing simultaneous competition and cooperation amongst card-issuing banking partners.

At the time, individual banks, such as Bank of America, retained “proprietary control of card networks and participating merchants,” and there was little-to-no “harmonization” amongst bank card issuers. One bank, Hock noted, issued cards with “a hole in the center” with a corresponding “steel peg on the merchants’ imprinting device” in order to keep these merchants from taking payments from competitor cards. However, the biggest issues were found in the settlement of payments itself, in which “sales drafts across multiple banks were sent via the mail,” leading to issues in the processing of transactions for the card-issuing banks. “Back rooms filled with unprocessed transactions, customers went unbilled, and suspense ledgers swelled like a hammered thumb,” which Hock claims led to counterfeit card fraudsters and scammers, and the ensuing early iterations of anti-fraud measures led to an even slower clearing process. When Hock’s bank, Seattle’s National Bank of Commerce joined the BankAmericard network in the late 1960s, their card transaction back end was “disintegrating.”

Hock joined “an ad hoc committee of fellow BankAmericard licensees” looking to improve the current situation. Together, this group developed “an entirely new approach to card acceptance and settlement” in forming “a distributed, decentralized network with clear rules governing the system and all participants having an equal voice and vote.” The novel organization structure network took the “development of the core card functions” away from the centralized Bank of America, giving every bank peace of mind that “standards would be developed only in the best interests of the network.” Due to Visa being jointly owned by every partner bank, the organization itself would “focus only on making payments work every time,” gaining “nationwide customer and merchant interest” while “building trust in the Visa brand.” Visa only succeeded if the entire system was able to meet the needs of every participating bank.

Hock’s vision for Visa dramatically reduced the amount of trust in order to scale the system quickly. If any partner bank was unable to settle a transaction for a merchant, Visa covered it for the indebted party, every time. Any such default was to be covered by Visa, and thus in lieu of every partner having to rely on one another, they only “had to trust American banking as a whole” and that the guarantee of settlement from Visa was sound. Visa thrived quickly, creating “the first electronic transaction authorization, clearing and settlement process systems” by 1973, with the Visa network going international the next year, and the issuance of the first Visa debit cards by 1975. The network grew “10,000% between 1970 and 2010” and become undeniably one of the most recognizable brands in the world. This is all despite the fact that most customers “generally don’t know what Visa does.” Hock believes that “the better an organization is, the less obvious it is.”

“Members are free to create, price, market, and service their own products under the Visa name,” Hock stated. “At the same time, in a narrow band of activity essential to the success of the whole, they engage in the most intense cooperation.” This novel blend of both cooperation and competition allowed Visa to grow worldwide despite the differing use of region-specific currencies, legislations, and languages, not to mention vastly differing political and cultural spheres. “It was beyond the power of reason to design an organization to deal with such complexity,” says Hock, “and beyond the reach of the imagination to perceive all the conditions it would encounter.” Instead, he says, “the organization had to be based on biological concepts to evolve, in effect, to invent and organize itself.”

Visa has been called “a corporation whose product is coordination.” Hock refers to it as “an enabling organization.” “Visa has elements of Jeffersonian democracy, it has elements of the free market, of government franchising — almost every kind of organization you can think about,” he explains. “But it’s none of them. Like the body, the brain, and the biosphere, it’s largely self-organizing.” Hock further boasts that “inherent in Visa is the archetype of the organization of the 21st century.” Hock would lead Visa until retiring in 1984 for “a second career of promoting” what he described during a talk at the Sante Fe Institute as “chaordic” networked organizations, which combine “chaos and order in the pursuit of growth,” It was during this lecture that Hock met Joel Getzendanner, the Vice President of the Joyce Foundation, which later gave him a grant to cover his travel expenses while exploring “the possibilities of implementing chaordic organizations,” which he would do with the formation of the Chaordic Alliance. The New Mexico institute was co-founded by Nobel winner Murray Gell-Mann and received $25,000 from Epstein in 2010, with Epstein’s bio on his website citing him as “actively involved” in the institute. Gell-Mann had been friendly with Epstein and previously thanked him for contributions to the Santa Fe Institute in his 1995 book, The Quark and the Jaguar. Pierre Omidyar is also intimately connected to the Institute and sits on its board.

Hock’s «chaordic» vision that he used to build Visa likely colored his views on digital currency, namely Bitcoin. In 2015, upon joining Xapo’s advisory board Hock stated that “Bitcoin represents not only the future of payments but also the future of governance.» “We live in the 21st century but are still using command and control organizational structures from the 16th century. Bitcoin is one of the best examples of how a decentralized, peer-to-peer organization can solve problems that these dated organizations cannot. Like the Internet, Bitcoin is not owned or controlled by any one entity, so it presents incredible opportunities for new levels of efficiency and transparency in financial transactions.”

Despite Hock’s retirement in the mid-1980s, Visa itself continued to innovate within the digital currency sphere, including a successful settlement transaction of Circle’s dollar stablecoin USDC to Visa’s Ethereum address held at Anchorage Digital in 2021. “Visa came to us in 2019 with an idea — make secure, efficient, and seamless settlement payments possible in digital currency, by linking Visa’s treasury with Anchorage’s custody platform,” says Diogo Mónica, Co-Founder and President of Anchorage. “This would give the next generation of crypto native issuers the option to directly settle with Visa in a digital currency over a public blockchain.” Within the press release, Visa states “the implications of our work with stablecoins are potentially far reaching — enabling our ability to one day support new Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDC) as they become available.”

The Xapo Advisory Board: John Reed

Born in Chicago and raised in South America, John Reed joined Citicorp in 1965 and, by June 1984, was named CEO of the bank, taking over for former CEO Walton Wriston. There must have been something in the water cooler at Citicorp in the decades before Reed took over for Wriston, for both bank leaders made profound, prophetic statements on the evolution of money as it entered the information age. “Information about money has become almost as important as money itself,” explained Wriston, while Reed further articulated that “banking is just bits and bytes.”

“I joined First National City Bank [renamed as Citibank in 1976] in 1965 and took a job in the international division, which Wriston ran,” Reed told Euromoney. Wriston became CEO two years later in 1967, and at the time, the bank had rules for compulsory retirement at age 65. While these rules led to Reed taking over for Wriston in 1984, the then-CEO hired Tempo (“a part of GE where Walt sat on the board”) to create a forward-looking collection of books attempting to predict “what the world would look like in the year 2000.” According to Reed, “the books looked at various fields: one was on energy and predicted we would have a hydrogen economy with energy produced from water; another was on computers.” Reed claims he had “some knowledge of computers” and “had done a little coding” by the time “Wriston walked into my office” and “threw this book at me.” Wriston told him to read it in order to “try to figure out what it all means for the banks and what impact it could have on us.”

Reed quite obviously took the ask quite seriously and spent several months assessing the “likely future relationship between banking and computers” while making visits to industry leaders such as IBM. “It would have been easy to talk about mainframes and automating processes. The first airline computer reservation system had just been launched.” Reed advised Wriston that “the future would be about online interaction between banks and their customers via computers, and we started a business based on that idea here, in Cambridge, called Citicorp Systems Inc.” “It is interesting just how long it has taken for technology to take over banking. Indeed, it has not happened yet. Banks don’t know how to run technology. And technologists don’t understand the banking business, customer management and marketing.”

Reed hired a number of people from a General Electric business currently working on electronic cash registers and divided the incoming staff into teams working on retail facing technology with the other on business customers. “We wanted to put a terminal on the desk of every corporate treasurer we did business with so that instead of having to ring the bank every day to check where that $1 million payment due in from Brussels or Paris had gone, treasurers would be able to see for themselves.” Citicorp was certainly on to something and this initiative led to one of the most disruptive innovations in banking history. “It led quickly to the idea of companies moving money electronically, initiating their own transactions rather than ringing the bank and asking us to do it. That was the beginning of the funds transfer business that became a very big and profitable one for Citibank.”

The second evolution of this team later built out the first automated teller machines, known as ATMs, as well as the novel network and protocols needed to run them. “We had literally to build them ourselves, including all the technology – multipliers, concentrators and central files – to bring them to market,” explained Reed. “I went to IBM and asked if they could build them and they told me: ‘No, we can sell you what’s in our catalogue; we don’t just build machines that you would happen to like.’”

The first ATM available for public use was installed in a Queens Citibank branch during 1977. By the start of 1978, there were “two at every branch in New York,” with one serving as a back-up in order for the bank to be sure customers had 24 hours access to ensure its widely marketed claim that “Citi never sleeps.”

“You would not believe how slow computation was in those days. But we knew that if a customer came to the machine and put their card in, we couldn’t have them waiting five minutes for the machine to respond. So, in the process of building the ATM, we created the first database manager operating across distributed computers.” For Piyush Gupta, the CEO of DBS, who came up with Reed during nearly 20 years at Citicorp, Reed was “50 years ahead of his time.” “He used to talk about Citi being an information bank. Other than the fact we used data for credit cards, I didn’t see how anyone would make a financial business out of information. But today when I reflect on big data, it’s what Reed was talking about all those years ago.”

“Financial services have remained largely untouched by the digital revolution,” explained Reed upon joining Xapo’s advisory board in 2015. He also stated that: “Bitcoin represents a real opportunity for changing that. Money at its core is simply a ledger for keeping track of debts and Bitcoin is truly the best iteration of a universal ledger we’ve ever seen. The mere fact that there will never be more than 21 million bitcoins and that each bitcoin can be divided into 100 million units makes it a significant improvement on any historical form of currency.”

“You almost sense there has to be an Uber moment in banking. If I had stayed in the industry after Citi, I probably would have looked to someone like PayPal rather than another bank.” Reed believed it was possible that big banks would be disrupted by technology companies. “Knowing your customer is not the sole province of Facebook and Google. I would rather be J.P. Morgan. Banks know everything about what you do with money, where it comes from, what you spend it on, your taxes. When I was running Citi, we didn’t have artificial intelligence and machine learning, but we knew when people got paid, what they would spend. Sometimes we might know they were heading for divorce before they did, because we could see their partners going crazy on their credit cards. If you really want to know consumers, I would go through the financial door.”